How ‘chip war’ puts nations in technology arms race

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

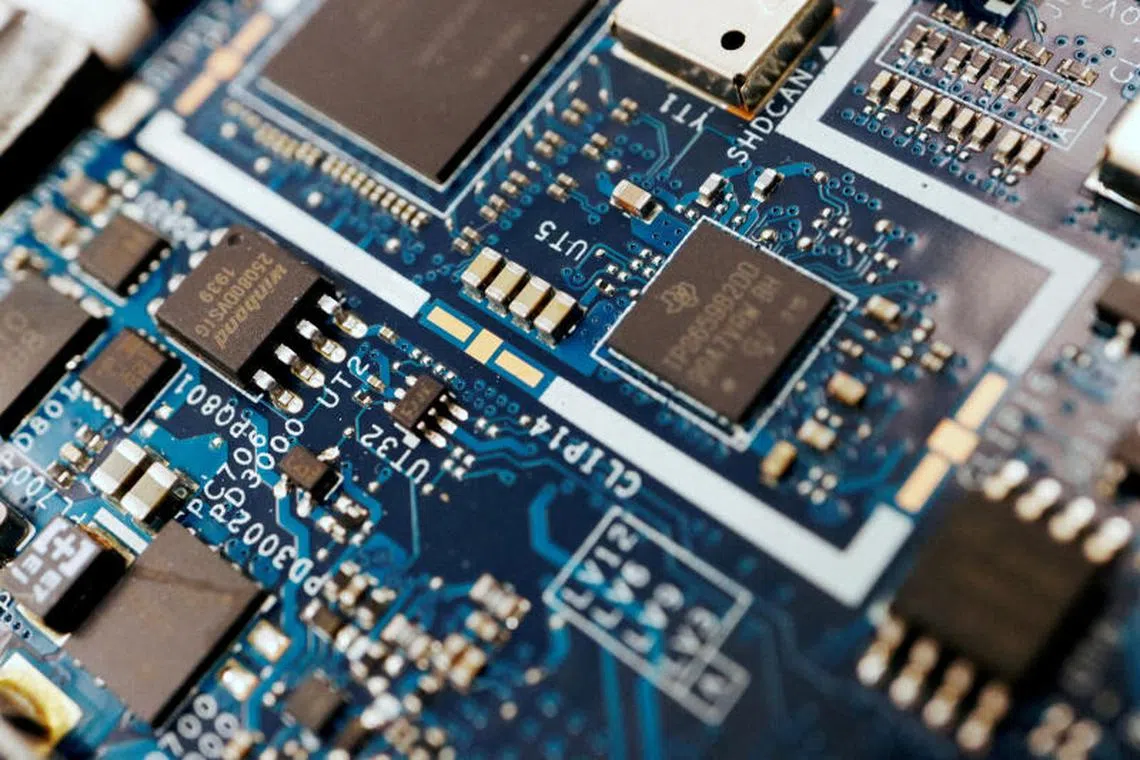

Chipmaking has become an increasingly precarious business.

PHOTO: REUTERS

San Francisco – The high-stakes business of making semiconductors – integrated circuits or, more commonly, just chips – has always been a battle of corporate giants. Now it is also a race among governments.

Because they are so difficult and costly to produce, there is a worldwide reliance on just a handful of companies, a dependence that was brought into stark relief by shortages during the Covid-19 pandemic. Access to chips has also become a geopolitical weapon, with the United States ratcheting up curbs on exports to China

1. Why the war over chips?

Chipmaking has become an increasingly precarious business. New plants have a price tag of more than US$20 billion (S$27 billion), take years to build and need to be run flat-out 24 hours a day to turn a profit. The scale required has reduced the number of companies with leading-edge technology to just three – Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), South Korea’s Samsung Electronics and the US’ Intel.

Chipmakers are under increasing scrutiny over what they sell to China, the largest market for chips. National security concerns, shifts in the global supply chain and shortages have governments from the US and Europe to China and Japan rushing to subsidise new factories and equipment.

2. Why are chips so critical?

They make electronic gadgets smart. Memory chips, which store data, are relatively simple and are traded like commodities. Logic chips, which run programs and act as the brains of a device, are more complex and expensive. And as the technology running devices – from rockets to refrigerators – is getting smarter and more connected, semiconductors are ever more pervasive. That explosion has some analysts forecasting that the industry will double in value this decade. Spending on research and development for chips is dominated by US companies, with more than half the total.

3. Is the world short of chips?

Covid-19 lockdowns and supply chain disruptions

4. How’s the competition going?

In October, the US imposed tighter export controls on some chips and chipmaking equipment

China’s chipmakers still depend on US technology, and their access is shrinking. A huge Chinese spending spree has not succeeded at creating sufficient domestic supply of vital components.

US politicians have decided that they need to do more than just hold back China. The Chips and Science Act, signed into law in August, will provide about US$50 billion of federal money to support US production of semiconductors and foster a skilled workforce needed by the industry. All three of the biggest makers have announced plans for new US plants.

The key test of the US containment policy around China comes with efforts to get allies to apply similar restrictions to their local companies. In late 2022, negotiations to bring the Netherlands and Japan into alignment were dragging.

Europe has joined the worldwide race to reduce the concentration of production in East Asia. European Union officials are wooing TSMC and other chipmakers to meet a goal of doubling production in the bloc to 20 per cent of the global market by 2030. Intel has already committed to building a plant in Germany.

5. How does Taiwan fit into all this?

Taiwan emerged as the dominant player in outsourced chipmaking partly because of a government decision in the 1970s to promote the electronics industry. TSMC almost single-handedly created the business of building chips designed by others, one that was embraced as the cost of new plants skyrocketed. Large-scale customers like Apple gave TSMC the massive volume to build industry-leading expertise, and now the world relies on it. Matching its scale and skills would take years and cost a fortune.

Politics have made the race about more than money, though, with the US signalling that it will continue efforts to restrict China’s access to American technology used in Taiwan’s foundries. China claims the island, just 160km off its coast, as a renegade province to be taken back by force if necessary and has threatened to invade to prevent its independence. Recent military exercises by Beijing have reignited concerns about the world’s dependence on Taiwan for chips. BLOOMBERG