US stocks sink with S&P 500 in correction as Trump policies stir economic fears

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

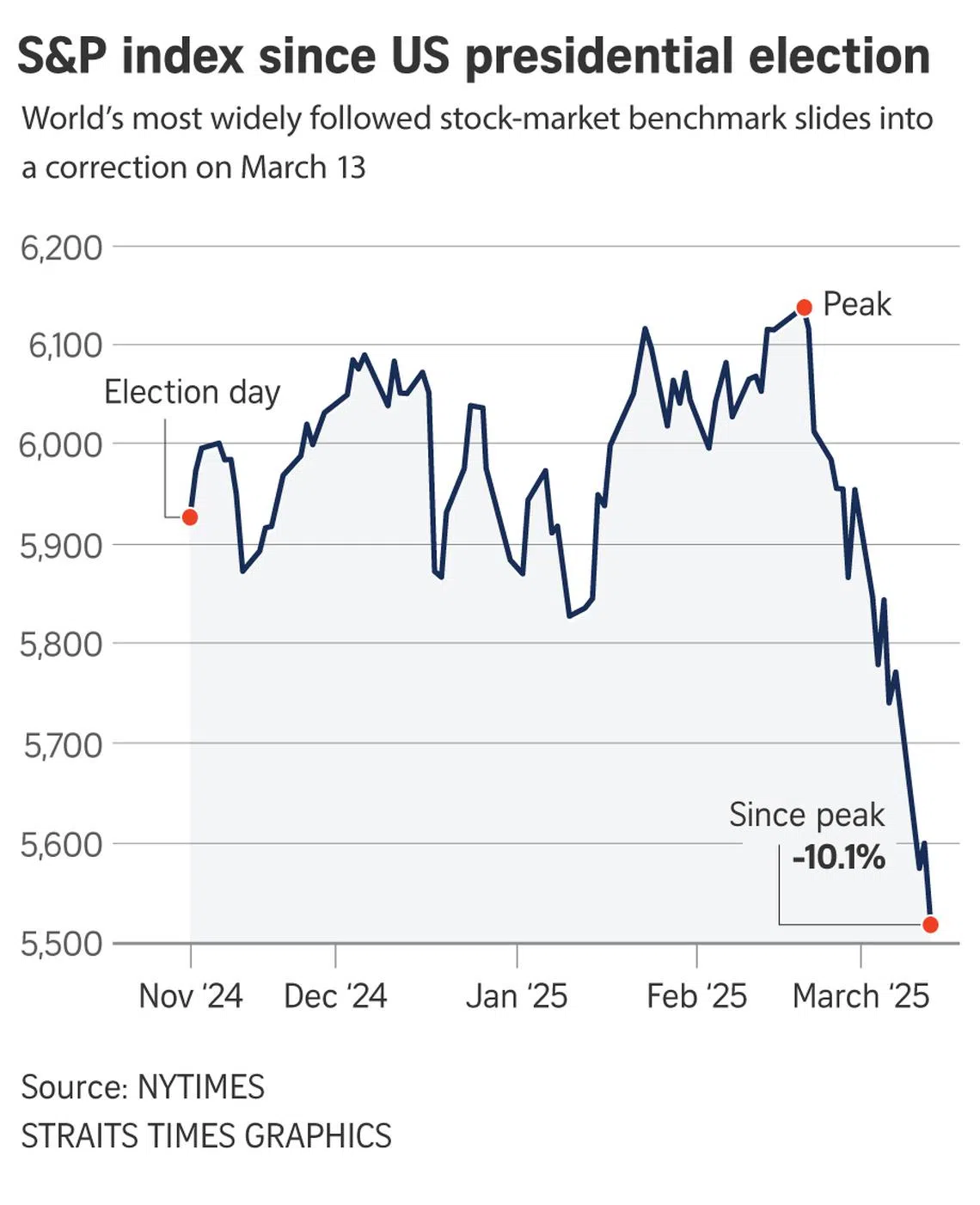

The world’s most widely followed stock-market benchmark – the S&P 500 – is now down more than 10 per cent from its peak.

PHOTO: AFP

Joe Rennison and Danielle Kaye

Follow topic:

NEW YORK – The world’s most widely followed stock-market benchmark slid into a correction on March 13, a drop that underscores how the two-year-long bull market is running out of steam in the early days of the Trump administration.

The move stems from investors’ growing pessimism about the whipsawing policy pronouncements from Washington over the past few weeks. On-again, off-again tariffs and mass layoffs of federal workers have fomented unease on Wall Street.

On March 13, the S&P 500 fell 1.4 per cent. After weeks of selling, the index is now down 10.1 per cent from a peak that it reached less than one month ago and is in a correction – a Wall Street term for when an index falls 10 per cent or more from its peak, and a line in the sand for investors worried about a sell-off gathering steam.

Other major indexes, including the Russell 2000 and the Nasdaq composite, had already fallen into correction. On March 13, the tech-heavy Nasdaq fell 2 per cent, while the Russell 2000 index of smaller companies, which tend to be more exposed to the ebb and flow of the economy, ended 1.6 per cent lower.

The deeper worry among investors is that uncertainty around the effects of US President Donald Trump’s policies is causing consumers to spend less and discouraging businesses from investing. That could, in turn, drive the economy into a downturn, forcing investors to reassess company valuations.

“I think what markets are telling us is that they are very concerned about the potential for a recession,” said Ms Kristina Hooper, chief global market strategist at Invesco. “That is certainly not what markets expected going into 2025.”

This is the 11th correction in the S&P 500 since the 2008-09 financial crisis, according to data from Yardeni Research. Three of the previous downturns turned into bear markets, defined as a more severe decline of at least 20 per cent.

So far, the administration has brushed off the market turmoil. US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said on March 13 that he was focused on the “real economy”, downplaying signals sent by business leaders and investors. “I’m not concerned about a little bit of volatility over three weeks,” he added.

As stocks have been falling in recent weeks, the Trump administration has emphasised that its economic policies are designed to promote job growth over the long term, but could cause some market turmoil in the short term.

Ms Seema Shah, chief global strategist at Principal Asset Management, said the economy had already begun to be “negatively impacted”.

The pain has been acutely felt among the behemoth tech companies that drove the market higher in recent years, but their once-rallying share prices have since reversed course. The Nasdaq composite has fallen roughly 14 per cent from its peak in December.

The sell-off has also spread to other corners of the market, signalling broader concerns than simply a re-pricing of highly valued technology companies. The Russell 2000 has fallen 18 per cent from its peak in November, close to a fully fledged bear market.

Sectors of the stock market exposed to tariffs, like food producers, have slumped. The effects are being felt on other companies, like retailers and airlines, that are worried about a pullback among consumers should the economy enter a downturn.

On March 13, the low-cost retailer Dollar General said customer traffic fell in its most recent quarter, and the company predicted continued financial pressure. Delta Air Lines cut its financial forecast this week for the first three months of the year, citing less demand for domestic travel.

“So far in 2025, the US economy has only faced headwinds,” Ms Shah said.

On March 13, Mr Trump threatened to impose 200 per cent tariffs on European wine and champagne,

And when he was asked by reporters if he might offer a reprieve to Canada – one of the United States’ largest trading partners – he was adamant that he would not. “I’m sorry, we have to do this,” Mr Trump said.

The constantly moving goal posts have left investors so rattled that even recent good news about the economy has not had a calming effect. On March 13, a report on weekly unemployment claims came in lower than expected. On March 12, a better-than-expected reading of the consumer price index had briefly helped bolster stocks.

Investors are worried that tariffs, once in full effect, will push prices higher – hurting business and consumers. Mr Trump’s immigration policies and firings of federal employees through the so-called Department of Government Efficiency (Doge) are also looming in the backdrop, as is the threat of an impending government shutdown.

“The outlook for inflation depends more on tariffs, deportations and Doge than the backward-looking data releases right now,” said Mr Bill Adams, chief economist for Comerica Bank.

The 10-year Treasury yield, which underpins a range of borrowing costs, has been falling sharply since mid-January and ticked down again on March 13, a sign of concern among bond investors.

Oil prices also slipped on March 13, with Brent crude, the international benchmark, down 1.6 per cent to just under US$70 a barrel. Gold, a haven for investors, hit a record high