Book on S’pore’s AI story chronicles making of sector’s engineers, tech tip on perfect kaya toast

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

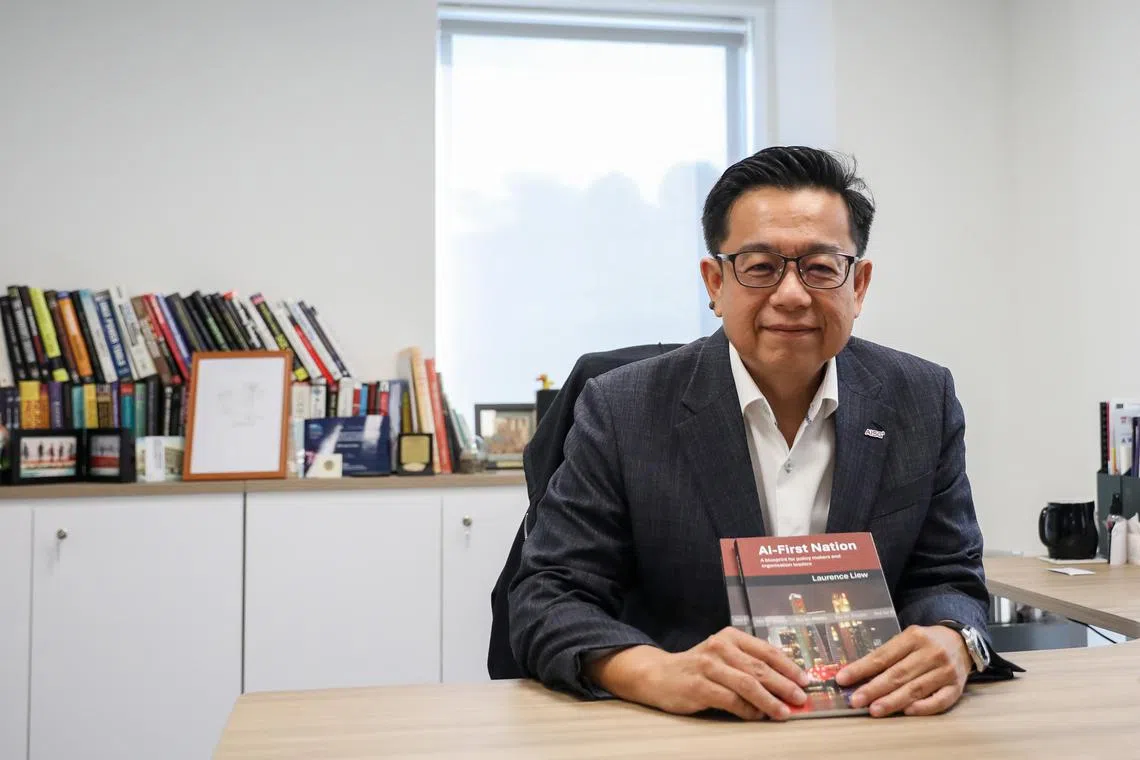

Mr Laurence Liew gives an insider's account of Singapore's AI journey in his book, AI-First Nation.

ST PHOTO: LUTHER LAU

SINGAPORE- If Ya Kun ever wishes to give it a go, artificial intelligence (AI) could help it serve up the perfect kaya toast, each and every time.

With cameras, data and an algorithm, the cafe chain’s customers will never risk having burnt toast, even if rookies were at the grill.

What it needs to do is listed on page 51 of a new book, AI-First Nation. The method would involve taking photos of good kaya toast for AI modelling.

Author Laurence Liew has diagrammed the instructions, and written the rest of the book, a chronicle of Singapore’s national AI programme called AI Singapore.

It will be the first in a series of six planned by the end of 2024, all with one aim – to help policymakers and corporate managers adopt AI.

“I want to get the Singapore story out there,” said Mr Liew, director for AI innovation at AI Singapore, in an interview.

AI Singapore’s work has drawn licensing and learning interest from countries in Europe, the Middle East, and even the Isle of Man, an island in the Irish Sea.

Set up in 2017 by the National Research Foundation (NRF), the programme brings together AI research and its ecosystem to give Singapore an edge in the hottest technology race today.

Over 142 pages, the volume gives Mr Liew’s account of AI Singapore’s initiatives, such as its 100 Experiments (100E) plan to pair AI researchers with firms to solve real-world problems, and its AI Apprenticeship programme to train a critical mass of AI engineers here.

The 100E project, it was revealed, did not appeal to the private sector at its debut.

Critics said that 18 to 24 months were too long for enterprises to wait for a piece of research to bear fruit, among other things.

The grumbles were addressed.

AI Singapore has since worked with tech firm IBM on solutions to predict merchandise return rates, with insurance firm Sompo to identify suspicious claims, and with dental firm Q&M to analyse X-rays.

AI Singapore’s apprenticeship programme, which has become the “crown jewel” and premier AI talent development programme in Singapore, was born out of need, Mr Liew wrote.

The centre’s first hiring call for engineers in August 2017 got a local drubbing, recalled Mr Liew, who was also AI Singapore’s first hire.

“We received over 300 resumes from all over the world, but only 10 were from Singaporeans,” he wrote. “We could not genuinely be AI Singapore, if the very backbone of our AI engineering team did not reflect our local talent pool.”

Yet, he noticed that in 2017, many Singaporeans were taking AI-related bootcamps, online courses and continuous learning and training classes.

“A training course originally costing $8,000 cost only $2,400 to a Singaporean participant, with the Government covering the remaining amount paid to the training centre,” he added.

It fuelled an AI-tuition boom, but some courses turned out to be practically useless, led by trainers with little real-world deployment experience.

Today, AI Singapore’s AI Apprenticeship programme has trained about 400 engineers, or about 100 each year.

Mr Liew dreams of 5,000 graduating a year in five years.

The programme is the most rewarding piece of his work, he said, but also the toughest. Not only candidates, but also their families, have to be persuaded.

Candidates have to leave their jobs to become apprentices, he explained.

Despite rigorous vetting, a handful would turn out to be poor picks, burdening their mentors who have to get them up to the mark.

“I cannot fail them. If I fail them, they’d have to pay me back the cost, fee and the stipend given to them. It could amount to, like, $80,000,” he said.

As expected from an outfit working at the edge of innovation, yet taking public funding and reporting to hierarchies, there were tensions, the book let on.

Mr Liew, who spent 25 years in the technology sector working for firms such as Microsoft, wrote about rumblings over his appointment made by the National University of Singapore (NUS), which won the government appointment to run AI Singapore.

“A few stakeholders believed an academic should assume the leadership of the various programmes, which is the customary procedure for NRF research grants given to universities,” he said.

He also broke conventions, which led Professor Ho Teck Hua – the then provost at NUS who hired him and went on to support his many projects – to label the university’s alumnus “his rebellious son”.

He said: “Sometimes the bureaucracy cannot react, or does not respond in a way that we think it should. Then we find other means to get the programme that we want done first.”

It means pushing ahead with projects such as introducing an AI sustainability metric, an unsanctioned idea he is now toying with.

In the foreword, Professor Yaacob Ibrahim, Singapore’s former minister for communications and information, said: “AI Singapore’s approach of ‘do first, apologise later’, while unconventional, has proven to be remarkably effective.”

The book, available on Amazon and Kindle for US$14.99, was written extensively with Google chatbot Gemini.

A US$20 (S$27) subscription to Gemini, and about US$100 for software to format, was all it took to self-publish the book, Mr Liew said.

“Typically a book will take 12 months, 18 months, or two years to write. This book took me three months with the help of generative AI,” he added.

“It is a way to show people that AI is real.”