Why Google Maps is still broken in South Korea: It might not be about national security any more

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

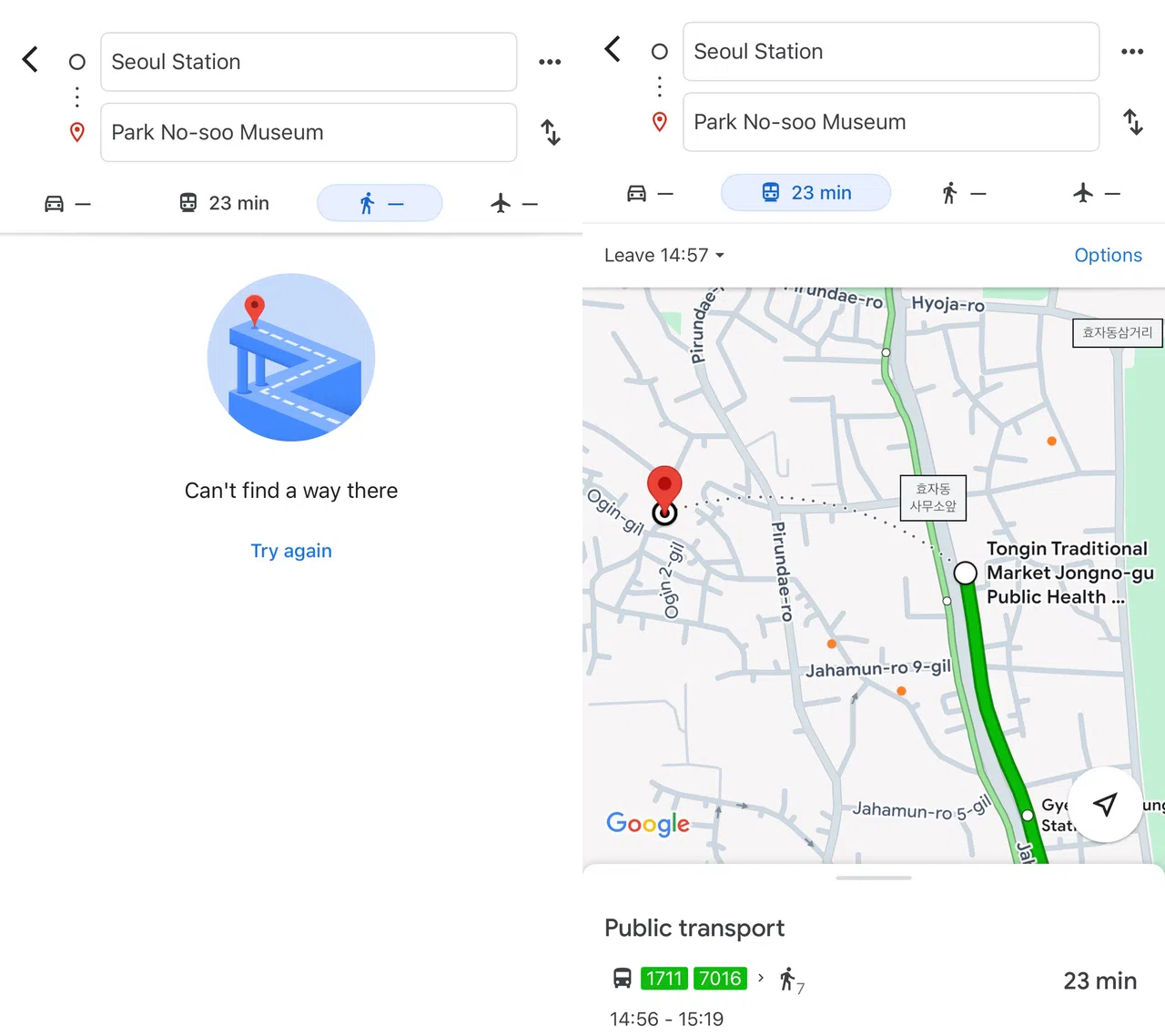

The “Can’t find a way there” screen on Google Maps. Google has repeatedly asked the South Korean government for permission to use its high-resolution digital base map.

PHOTO: SCREENGRAB FROM GOOGLE MAPS

It is 2025, and if you try to get walking directions in Seoul using Google Maps, you will still run into the same dead end: the “Can’t find a way there” screen.

For many tourists, it is both frustrating and baffling.

Google Maps offers turn-by-turn walking directions in cities as far-flung as Pyongyang, the capital of the hermit kingdom of North Korea – yet, in Seoul, one of the most digitally advanced cities in the world, it cannot guide you from your hotel to the nearest subway station?

For almost two decades, the issue has been blamed on national security. South Korea has strict laws that block the export of high-precision map data, supposedly to prevent misuse by hostile actors.

But in 2025, that argument is wearing thin and a more fundamental tension is coming into focus: Should Google be allowed to freely commercialise taxpayer-funded public data without meeting the standards that domestic companies must follow?

Google says it needs South Korea’s best map. But that’s only half the story.

The map at the centre of this issue is a government-built, high-resolution 1:5000 digital base map maintained by the National Geographic Information Institute (NGII).

It is publicly funded, annually updated and rich with layers like sidewalks, pedestrian crossings and road boundaries. Any South Korean citizen or entity can access and use it for free.

Google Maps in South Korea does not provide walking directions (left), and while it offers public transit routes with real-time updates, the walking segments are shown only as vague dotted lines (right) without step-by-step guidance.

PHOTO: SCREENGRABS FROM GOOGLE MAPS

Google claims that without exporting this data to its global servers, it cannot fully enable core features like walking, biking or driving navigation.

The global map giant, which relies on processing map data through its global infrastructure, has repeatedly asked the South Korean government for permission to export the NGII base map.

Its latest request, filed in February 2025, is the third since the issue first surfaced in 2007 and again in 2016. A final decision from the government is expected in August.

Screenshots from South Korea’s National Geographic Information Institute show the publicly available 1:25,000-scale map (left) and the more detailed 1:5,000-scale map (right).

PHOTO: SCREENGRABS FROM NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION INSTITUTE

But experts say Google’s “we can’t do it without the map” argument is overstated.

“Yes, the 1:5,000 map would help, especially for pinpointing pedestrian pathways,” said Kyung Hee University geographic information science professor Choi Jin-moo. “But Google could build the necessary layers on its own using its vast trove of satellite imagery and artificial intelligence processing, just like it does in countries that don’t share any base map data at all.”

The evidence is all around. OpenStreetMap, a crowdsourced platform, offers walking navigation in South Korea. So does Apple Maps, despite not having access to NGII’s data set or exporting any official Korean geospatial data.

Google already provides walking directions in places like Pyongyang, where mapping data is sparse, and in countries like Israel and China, which impose strict restrictions on geospatial exports.

“If Google can make it work in North Korea, then clearly the map is not the only barrier,” Prof Choi said.

Google Maps offers full walking (left) and driving (right) directions in Pyongyang, North Korea – features that remain unavailable in South Korea.

PHOTO: SCREENGRABS FROM GOOGLE MAPS

In other words, what Google gains by accessing the NGII map might not be feasibility, but convenience.

“Rather than spending time and money building its own map layer, it would get a ready-made foundation that is free, publicly funded and immediately monetisable through ads and API (application programming interface) licensing,” Prof Choi added.

South Korea’s national security argument is crumbling

South Korea’s longstanding concern is that exporting detailed mapping data could expose key infrastructure to hostile threats, particularly from North Korea. But experts argue that in 2025, this reasoning no longer holds up to scrutiny.

“You can already buy sub-metre commercial satellite imagery of South Korea from private providers,” said Sangji University military studies professor Choi Ki-il.

In its latest proposal, Google offered to blur sensitive sites if the government supplies coordinates. But even that sparked legal concerns. Under South Korea’s military laws, simply compiling a list of protected locations could be a violation.

The real issue, Prof Choi believes, is the symbolic discomfort of ceding data sovereignty to a global tech platform.

“There’s a psychological reluctance to let any part of our national digital infrastructure sit on foreign servers,” he said. “But we need to be honest about the threat level.”

“This is primarily about control, not national security or technical capability,” said Professor Yoo Ki-yoon, a smart city infrastructure expert at Seoul National University. “Google wants to integrate Korea into its global system on its terms, without storing data locally, without paying Korean taxes at the level domestic firms do, and without meaningful oversight.”

Who really stands to gain or lose?

The economic stakes are just as complex as the technical ones. South Korea’s location-based services market is worth more than 11 trillion won (S$10.2 billion) according to Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport data in 2023, with more than 99 percent of companies in the space being small or mid-sized.

These firms rely on the same public mapping data that Google wants, but they do so under heavy conditions. They must store the data domestically, pay full local taxes, and invest in additional surveying and development.

Giving Google free access, critics warn, could reshape the market in its favour. Developers might rush to build on Google’s API, only to find themselves locked into a system where prices spike later, just as they did in 2018 when Google restructured its Maps API pricing globally.

“There’s a risk of long-term dependency,” said Korea Tourism Organisation researcher Ryo Seol-ri. “Right now, Korean platforms like Naver and Kakao have limitations, but at least they’re governed by Korean rules. If Google becomes the dominant layer, we lose that control.”

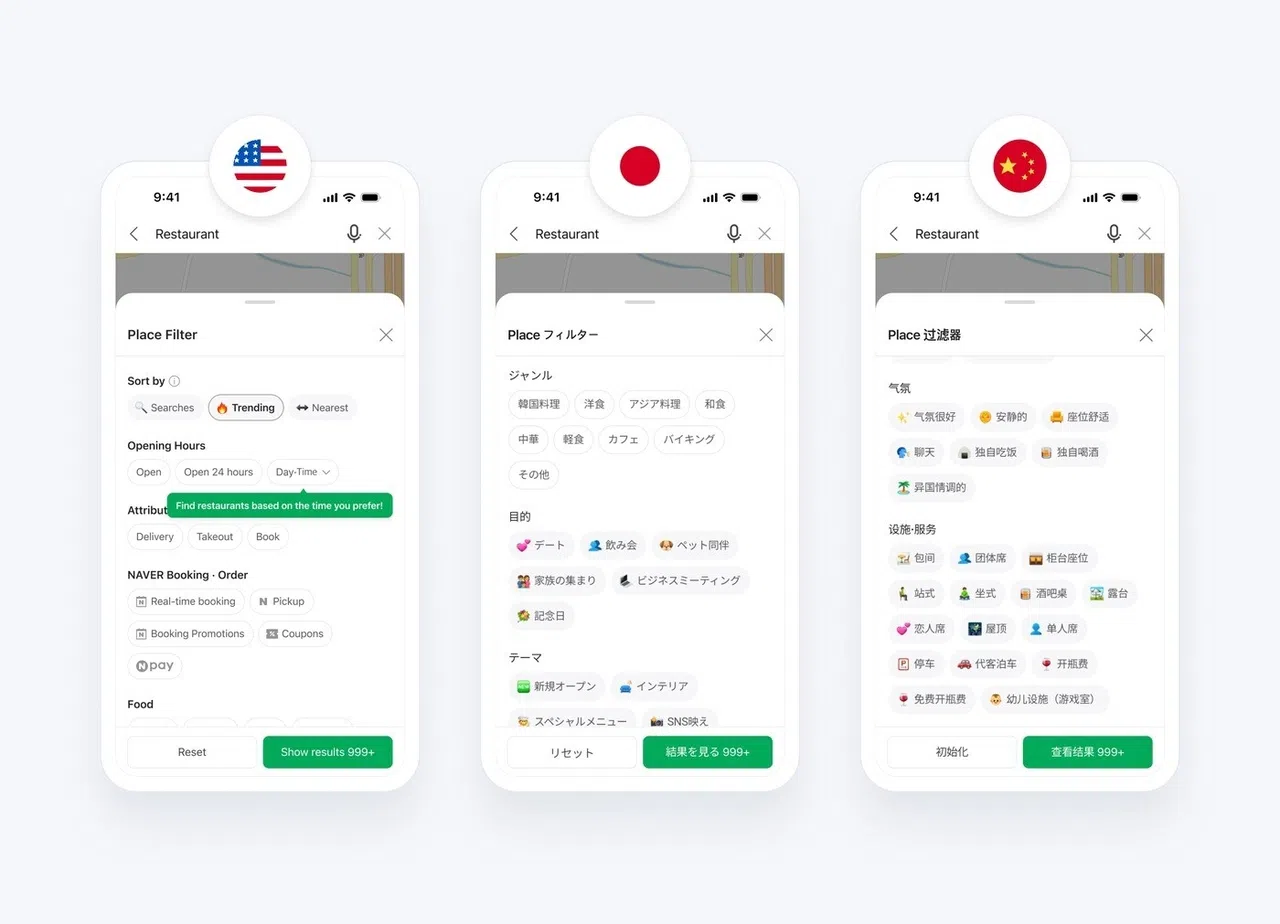

Despite launching a multilingual version back in 2018, Naver Map began expanding foreign-language support for place filters and business information like opening hours and amenities only in October.

PHOTO: SCREENGRAB FROM NAVER MAP

Still, the researcher admits that the issue is far from urgent for most stakeholders. “From a tourism perspective, this isn’t what drives people to or from Korea. Visitors are definitely inconvenienced, but they expect to be. It’s baked into the experience now.”

That may be the most important reason the situation has not changed, and likely will not any time soon.

There is no single player with the incentive to fix it. The South Korean government does not want to set a precedent by giving up control of its mapping infrastructure. Google does not want to build from scratch if it can pressure its way into a shortcut. And while tourists may grumble, broken Google Maps has not kept them from coming.

Tourism professor Kim Nam-jo of Hanyang University said: “Improving map usability would make Korea more tourist-friendly, sure, but it won’t suddenly boost visitor numbers. That’s why no one sees it as urgent enough to fix.” THE KOREA HERALD/ASIA NEWS NETWORK