News analysis

S’pore, other nodes in high-tech sectors face collateral damage as US tightens rules on chips

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

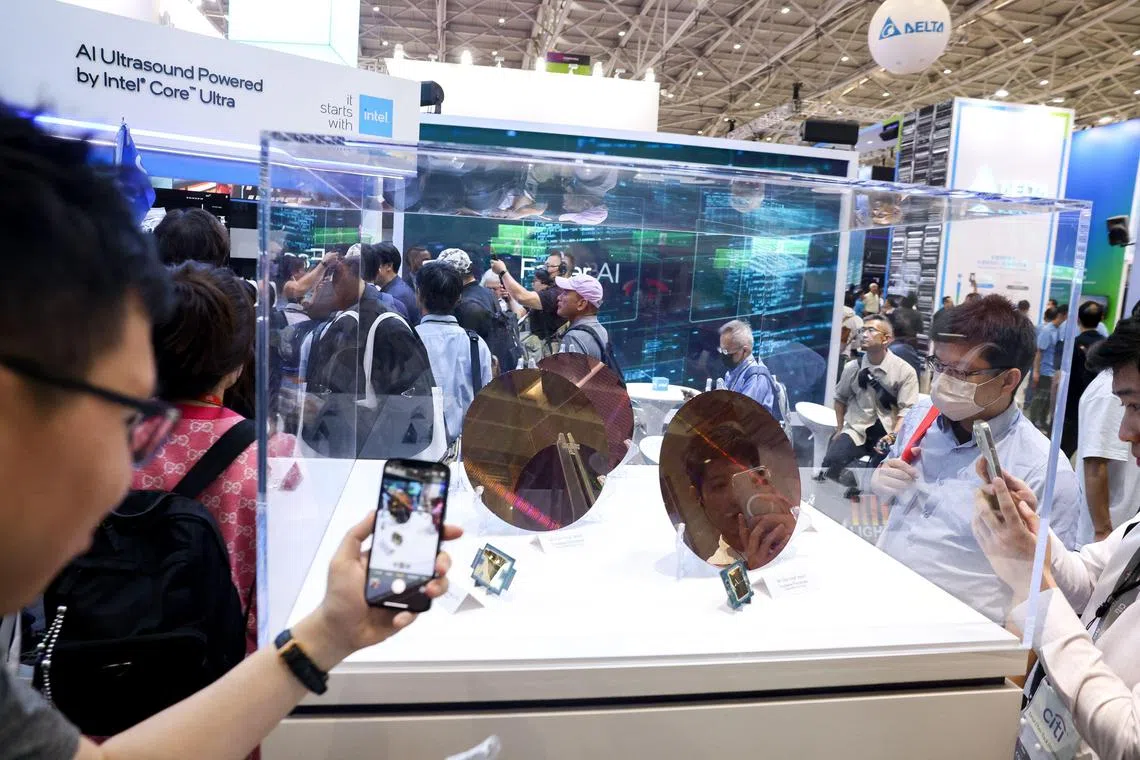

Wafer samples on display at a technology exhibition and trade show in Taipei in 2024.

PHOTO: AFP

SINGAPORE – US President Donald Trump is this week reportedly considering tighter rules on advanced chips

“In a more polarised world, Singapore’s access to high-end technology could be at risk,” Dr Michael Raska, an assistant professor in military studies at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore, says.

“Our open and highly connected economy, a strength in an era of globalisation, may now be a vulnerability as the superpowers raise trade barriers and controls in a bid to stem leakage and diversions,” he adds.

News reports of a US probe

It is a sobering reminder that the global economic order, premised on open markets and multinationals spreading their supply chains across the world, will face greater stress as geopolitics and national security take centre stage, with US-China competition becoming a defining feature.

Key nodes in high-tech sectors will come under greater scrutiny and face increasing risk of collateral damage.

Singapore is particularly susceptible to a US-China tech confrontation, as host to a series of activities in the chips value chain – from research and development to testing and manufacturing.

The Republic’s additional roles as a key transshipment hub along major sea lanes of communication and an attractive business hub for over 7,000 multinationals, with more than half making it their regional headquarters, mean more points of vulnerability.

Where will the new shockwaves come from?

The curbs reportedly under consideration by the Trump administration include further restrictions on the type and quantity of artificial intelligence (AI) chips a list of trade entities that cannot receive US tech, goods and services

Trump officials are also expected to put greater pressure on key partners to further limit China’s access to semiconductor equipment, especially Japan and the Netherlands, home to the two biggest firms that build chipmaking tools outside the US – Tokyo Electron and ASML

The news comes after DeepSeek, a Chinese AI start-up, sent shockwaves across the global tech sector

Most recently, the US introduced a tiered approach

Will the US broaden restrictions to more chips, including trailing-edge ones previously assumed not to make a qualitative difference to China’s computing power? Will it also tighten what can go through countries like Singapore?

Can chips be regulated like weapons?

The implementation of any new US restrictions is not without challenges.

Dr Raska notes: “It would be very hard for any one government to regulate such dual-use technology as if they were weapons systems.

“Doing so would require restrictions across every part of the assembly line, which is a profoundly difficult endeavour, even if the US were to enact the strictest and most comprehensive regulations centred on end users.”

The end-user certificate (or EUC) regime that governs arms sales ensures weapons are delivered only to approved recipients and not diverted to unauthorised parties.

It requires buyers to provide exporters with a legally binding document specifying the purpose and user of the equipment.

“EUC supply chains are also very well established, with clear exporters and customers. But how do you apply that to a technology like chips?” Mr Alex Capri, senior lecturer at NUS Business School, asks.

“The trouble also is that most governments do not have the resources available to be able to verify that such regulated technology ends up where it’s supposed to go.”

He thinks, however, that advances in regulatory technology like tracer dust could resolve that headache by employing microscopic particles that can track at all times products and verify their origin, and is already being deployed to fabrics and cocoa beans. But, he notes, this could create fresh legal challenges around data management, privacy and security.

Whatever the case and in whatever form curbs materialise in, Singapore will have to tread carefully, given the high stakes.

Speaking in Parliament on Feb 18, Second Minister for Trade and Industry Tan See Leng emphasised the importance of continued access to AI compute

“Our economic competitiveness is based on our commitment to the rule of law, zero tolerance for corruption, transparent regulations and an open, inclusive business environment.

“We have painstakingly built up this reputation over time. That is why we take firm and decisive action against individuals and companies that violate our laws,” Dr Tan said.

Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan, in response to questions, told Parliament that Singapore is not legally obliged to enforce the unilateral export measures of countries around the world.

“But we will enforce the multilateral agreed-upon export control regimes,” he said.

Dr Balakrishnan also emphasised that it is not in Singapore’s national interest to be exploited, stressing that companies will not be allowed to use their links with Singapore to evade unilateral export control measures that apply to them.

China pushed to accelerate its learning curve

Despite a slew of US restrictions rolled out since 2018 aimed at limiting China’s access to the most advanced chips and slowing its tech development, China has, over the past two years alone, achieved an impressive series of technological breakthroughs across a range of industries years earlier than predicted.

After Huawei’s use of Google’s Android was blocked in 2019, the company put thousands of engineers to work continuously in shifts over 24 hours to solve the problem and rewrite code.

The firm announced in November 2024 that its new smartphones and tablets from 2025 will run on a new operating system stripped of Android tech

This same storyline of technological breakthroughs on an accelerated timeline is playing out across the wider Chinese economy, with China’s first domestically made 7nm chip J-35 Gyrfalcon,

“China is closing the technological gap and signalling that the days of American monopoly on advanced technologies across all domains may be coming to an end,” Dr Raska says.

“This fight in chips is only symptomatic of an intensifying competition for strategic technology.

“We have seen how denying China access to high-end chips motivated the Chinese to put even more money and people behind the goal of catching up.”

Lin Suling is senior columnist at The Straits Times’ foreign desk, covering global affairs, geopolitics and key developments in Asia.