Why children keep dying from toxic Indian cough syrup

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

Since 2019, there have been at least 100 cases of child deaths linked to Indian-made cough syrups.

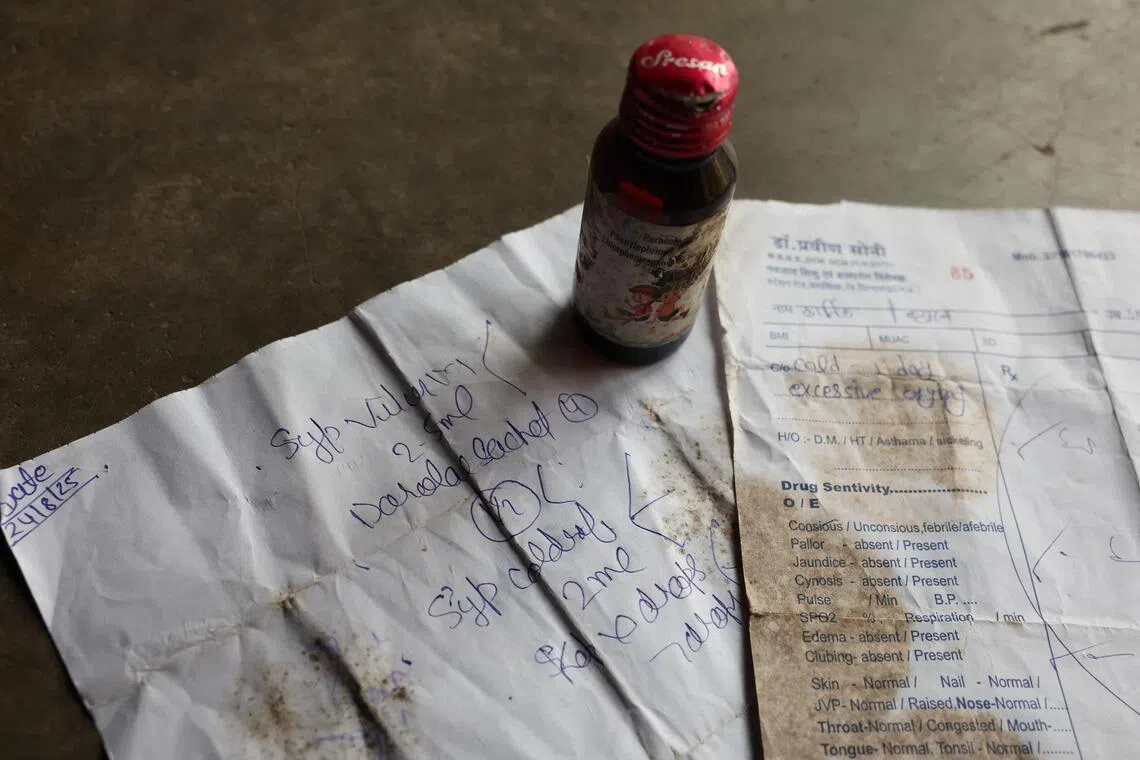

PHOTO: REUTERS

NEW DELHI – At least 22 children in India have died since early September after taking a toxic cough syrup, highlighting persistent quality-control failings in the country’s vast pharmaceutical industry.

The deaths prompted the Indian authorities to stop the production of three cough medicines, and on Oct 13, the World Health Organisation (WHO) issued a global alert to make sure the products had not entered other markets.

It is not the first time that Indian-made cough syrups have been linked to child deaths – at least 100 such cases have been recorded since 2019.

The latest incident has reignited scrutiny of India’s US$50 billion (S$65 billion) pharmaceutical industry, the world’s largest supplier of cheap, non-patented drugs.

With more than 10,000 manufacturing sites nationwide, regulators have struggled to keep up with inspections, and there have been complaints from abroad over the quality of some Indian medicines.

What caused the latest cough syrup deaths?

Since September, several children under the age of five – all from a small town in the central state of Madhya Pradesh – have died of suspected kidney failure, according to local media.

Health authorities said they had consumed Coldrif

Laboratory testing by local drug authorities showed that samples of the cough syrup contained an excess of diethylene glycol (DEG), a toxic substance often used as an industrial solvent.

They found that one batch of Coldrif contained 48.6 per cent DEG – way above the maximum of 0.1 per cent that is considered safe by the WHO.

Sresan representatives have not commented publicly on the case and did not immediately respond to an e-mail seeking comment.

What is diethylene glycol?

DEG is a colourless, odourless liquid that is often used in industrial applications such as antifreeze agents, brake fluid, dyes and resins.

Even small amounts of DEG, especially in young children, can cause serious kidney damage, which can lead to renal failure or death.

DEG can make its way into cough syrup through contamination somewhere in the supply chain, or when it is used as a substitute for another ingredient.

It is chemically and physically similar to high-purity, pharmaceutical-grade glycerin and propylene glycol – essential base ingredients for cough syrup – but costs only a fraction as much.

It is still unclear how and when DEG entered the supply chain in the case of the contaminated Coldrif syrup.

What action have Indian authorities taken?

Some Indian states ordered an immediate halt to the production of Coldrif, suspended product sales and issued a recall of the medicine. The Health Ministry initiated criminal proceedings against Sresan Pharmaceuticals on Oct 6 and its owner G. Ranganathan was arrested on Oct 9

Sresan’s manufacturing license was revoked and the company was ordered to shut down, according to Press Trust of India. An investigation by the state Food and Drug Administration found the company lacked proper manufacturing and laboratory practices, and had recorded more than 300 critical and major violations.

Tamil Nadu officials were due to conduct a detailed inspection of other drug manufacturers in the state.

The Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission, which enforces drug standards, has now introduced mandatory DEG testing for all oral liquid medicines.

Another drug regulator, the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation, asked regional watchdogs to ensure raw materials and finished formulations are tested before they are released to the market.

India’s Health Ministry urged “rational use of cough syrups, particularly among children”.

The country faces a problem of excessive use of antibiotics, such as pills and syrups to treat common colds, often sold over the counter with minimal checks.

Has the contaminated Indian cough syrup been sold in other countries?

Indian drug regulators said the contaminated medicine had not been exported, and the US Food and Drug Administration stated it was not shipped to the US.

WHO nonetheless issued a global alert over three cough syrups made in India: Coldrif, Respifresh TR – made by Rednex Pharmaceuticals – and ReLife from Shape Pharma.

It asked national health authorities around the world to check whether any of the products were available in their countries, advising increased surveillance in markets with informal and unregulated supply chains.

Have there been other instances of DEG poisoning?

There have been several other deadly cases of DEG poisoning linked to contaminated cough syrups in recent years.

In 2019, at least 12 children died in India’s Jammu and Kashmir after consuming tainted medicine. A few years later, DEG-contaminated syrups were tied to the deaths of about 70 children in Gambia, and 18 in Uzbekistan.

WHO concluded that the syrup sold in Gambia was made at an Indian factory run by Maiden Pharmaceuticals.

Indian authorities later disputed that finding, arguing that the deaths were not linked to the factory, and blamed the Gambian government for failing to test the medicine.

In the Uzbekistan case, Indian investigators concluded that contamination occurred at the Marion Biotech plant. The company’s operating licence was rescinded following the deaths, but a court reinstated it in June 2025.

What does this mean for India’s pharmaceuticals industry?

There have been regular complaints from regulators and public health experts abroad over medicines made in India, including cough syrups, eyedrops, cancer treatments, abortion pills and antacids.

Nevertheless, demand for the country’s pharmaceutical exports is still growing, and health industry regulators do not have enough staff to effectively police the expanding industry.

Coordination between India’s national drug agency and state-level organisations is poor, according to health campaign groups, and there is a lack of clear data about manufacturers operating in the country.

Chemical supply chains are also poorly monitored, making it possible for drug ingredient manufacturers or their middlemen to switch standard products for cheaper substitutes to increase their profits, without necessarily being aware of the potential consequences. BLOOMBERG