South Asian Symphony Orchestra strikes the right notes for peace

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

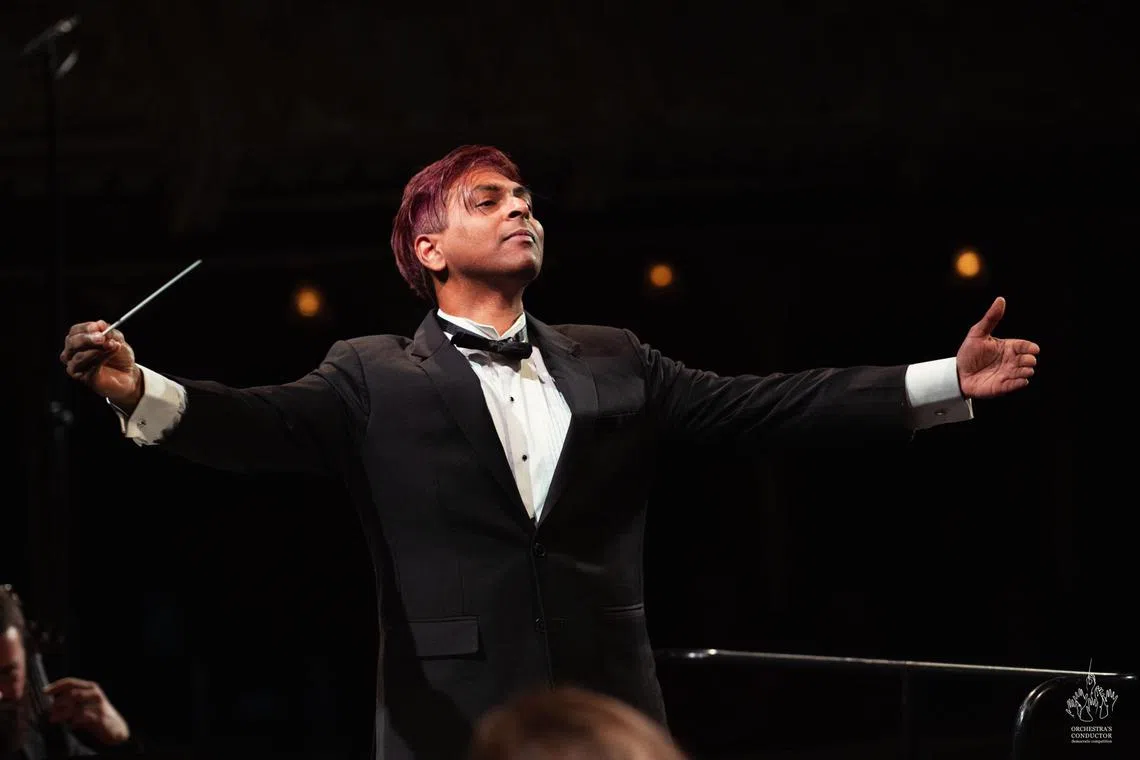

The South Asian Symphony Orchestra's Singaporean conductor Alvin Arumugam.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF ALVIN ARUMUGAM

NEW DELHI - A few days earlier, the concert stage was a lively scene as musicians warmed up during rehearsal. Strings bowed, woodwinds blew and brass bellowed, adjusting tempo and tune as a team.

What may have seemed like musical dissonance to the casual onlooker gelled into a harmonious whole on the day of the concert, on Nov 23 in New Delhi. As the musicians took their seats and the welcoming applause died out, a hush descended upon the 300-plus audience, which held its breath in a collective feeling of anticipation.

And as Singaporean conductor Alvin Arumugam’s baton swung into action, the disparate instruments spoke their parts, notes and pitches melding into a cohesive whole, taking the listeners to a musical idyll.

That evening, to a diverse audience of families with young children, college students and well-dressed concert regulars, the South Asian Symphony Orchestra (Saso) channelled works by famous Western classical composers of yore. Ludwig van Beethoven and Felix Mendelssohn were on the musical menu, paired with a new piece by 23-year-old Indian composer Aryaman Joshi featuring the tabla and celebrating India’s successful moon landing.

On stage, an Indian violinist, a Sri Lankan double bassist and a Pakistani-American violist were among the 40 or so members of the Western symphony orchestra, helmed by a Singapore-born conductor with roots in Sri Lanka and Malaysia – all bound together more by their love for music than by their differences.

The five-year-old Saso was created by the South Asian Symphony Foundation. Co-founded by former diplomat Nirupama Rao and her retired bureaucrat husband Sudhakar Rao, the non-profit trust based in Bengaluru seeks to build peace and mutual understanding in South Asia through music and its orchestra.

A former Indian foreign secretary, Mrs Rao believes an orchestra, with its diverse players and instruments, is an apt illustration of what a society ought to be like with its many peoples, myriad languages and different ideologies, especially in South Asia “where we have few modes of communication among ourselves”.

South Asia extends from Afghanistan, through Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and Bhutan, and through India, Sri Lanka and to the Maldives.

In an orchestra, “as strangers, you meet and get to know each other, you collaborate, you create harmonies together... There is no small, there is no big here. Each and every one makes a vital contribution,” Mrs Rao told The Straits Times, seated in an auditorium in Delhi’s iconic Lotus Temple complex, where the orchestra performed on Nov 23.

Founder-trustees of the South Asian Symphony Foundation, Mrs Nirupama Rao (left) and Mr Sudhakar Rao (right).

ST PHOTO: DEBARSHI DASGUPTA

Over the years, Saso’s musicians have come from across the region, including Afghanistan and Nepal, the global South Asian diaspora, as well as other countries such as Thailand, Malaysia and the US.

Then there is Singapore, whose double bassist Loewe Lim played at the two recent concerts in Delhi on Nov 22 and 23 that were conducted by Mr Arumugam, who grew up in the Republic.

The musicians practise their respective parts individually for several weeks and gather together a few days before a scheduled performance to prepare and rehearse.

Building peace through music

Since debuting in Mumbai in 2019, and barring the pandemic years, Saso has held one or two free concerts every year in India, trying to strike the right notes as it aims for peace and unity in a region fraught with tension.

Neighbours India and Pakistan, for instance, have not had operational flights, train or bus services for more than five years now. Yet, underlying these physical divisions are longstanding cultural affiliations that the orchestra hopes to build on.

Here, the same ghazals and folk songs are enjoyed with equal fervour on both sides of the border, sung in Urdu and other common languages, despite intense hostility between the two countries. South Asia is also a region where the same poet, Rabindranath Tagore, penned and composed the national anthems of two countries – India and Bangladesh.

Each time the orchestra’s musicians play on stage, regional acrimony is drowned out with its concertos and national boundaries blurred with its symphonies.

The South Asian Symphony Orchestra receives a standing ovation from the audience in Delhi after its performance on Nov 23.

ST PHOTO: DEBARSHI DASGUPTA

For Ms Andrea Leitan, a 36-year-old Sri Lankan double bassist who has been a part of Saso from the start, music transcends barriers such as language, skin colour and looks. “It can go beyond what you wear, what you eat. It goes beyond all of that,” added the musician, who is also with the Symphony Orchestra of Sri Lanka.

Weaving and directing disparate strands into a united and cohesive whole is Singapore’s Mr Arumugam, who has been Saso’s conductor since its inception.

Mr Arumugam is based in London in the United Kingdom, where he is conductor of The Clio Project, a symphony orchestra that focuses on operas. A 2024 winner of the Orchestra’s Conductor Competition in Romania, he is also music director of the Singapore-based Musicians’ Initiative orchestra that wants to make classical music accessible to all.

Helming an orchestra like Saso has taught him to appreciate differences while finding similarities, he told ST. “When an orchestra like this comes together, you very quickly find what connects you and for us, it is the music that is right in front (of us).”

The workings of an orchestra, as a microcosm of larger society, can show people how they can get along with one another, be it as musicians or world leaders. “If within the first five to 10 minutes, I can get an orchestra to agree on temperament, on the direction of the music, phrasing, articulation, balance, nuance, without even speaking, then it should be possible for world leaders to do the same,” he said.

Singaporean conductor Alvin Arumugam has been the South Asian Symphony Orchestra’s conductor since its inception.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF ALVIN ARUMUGAM

‘There’s something about music that unites’

Yet, leaders in South Asia have failed to cast aside differences and establish trust to deal with common challenges. The last summit of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation, an organisation to build a connected and integrated South Asia, was held a decade ago, in November 2014.

The forum has been stymied by persistent tension between India and Pakistan, which are going through one of their most adversarial phases. Neither of the two countries have had a high commissioner in the other’s capital since 2019, the year in which a terror attack killed 40 Indian security personnel in Jammu and Kashmir, one that India blamed on Pakistan.

And when India revoked Jammu and Kashmir’s special status later that year, a region that both India and Pakistan claim as their own, ties plummeted further.

Despite the tempestuous relationship, it is music that has reminded Indians and Pakistanis of their shared cultural and linguistic heritage, which gives cause for hope. Even as Indian films continue to enthral fans across the border, Pakistani music has won millions of Indian fans, in particular through Coke Studio. The music television series sponsored by drinks giant Coca-Cola features live studio-recorded performances by various artistes, with its distinct South Asian-inspired mix of Sufism, rock and pop.

Mr Nasr Ali Sheikh, 29, a Pakistani-American violist who has performed with Saso, agrees that music is “a brilliant way of bonding one country to another”. “There’s something boundless about music that unites us by transcending us away from our individual worlds,” he added.

“It is important to see our roots are not too far apart”, added Mr Sheikh, whose paternal grandmother lived in India before Pakistan was carved out of India in the 1947 Partition.

In a colourful display of diversity, Saso players often perform garbed in their national costumes. Every concert, styled as “Peace Notes”, begins with Maithreem Bhajata, a Sanskrit invocation calling for friendship among all nations that is sung by a classically trained Indian singer.

Nor is its symphonic repertoire entirely Eurocentric.

Apart from classical staples by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Giacomo Puccini, Saso is sure to include music from South Asia in its programme. At its inaugural performance in Mumbai in 2019, the audience was delighted when the orchestra struck up with Hamsafar, a medley of popular songs from several South Asian countries, including Bhutan and Afghanistan.

And this time in Delhi, when the orchestra launched into the foot-tapping Zoobi Doobi ditty from global Bollywood hit 3 Idiots, the audience broke into spontaneous applause, kept up their rhythmic clapping and demanded encores at the end of the show.

In a tangible nod to the region’s cultural heritage, Saso also features South Asian musical instruments in its performance pieces. These include the bansuri, an Indian bamboo flute blown from the side, and the rubab, a popular Afghan lute-like string instrument.

Sri Lankan percussionist Neomal Weerakoon, 46, who has performed with Saso from the very beginning, recalls the Hamsafar medley being an “eye-opener” for him and the orchestra’s other musicians. Had it not been for the scores that identified each of the song’s provenance, they would not have been able to identify the origins. But they could all relate to the songs musically.

“It really kind of illustrated that we are all interlinked through a common culture,” said Mr Weerakoon, who has struck up friendships through the orchestra with a fellow-percussionist from Bhutan and others in different parts of South Asia.

To be sure, a Saso concert often leaves its listeners a little more than musically entertained.

Mr Siddharth Bubna, a 31-year-old business development professional who attended the Nov 23 concert in Delhi, mused about how music can break the ice and form a connection between strangers. He recalled a trip to Taiwan when his taxi driver played an Indian song, and they bonded over the music.

This could apply on a wider scale, at a level where even nations are involved, he said, adding: “If the ice is not broken, then there’s no chat, there’s no dialogue happening.”

Five years on, Saso’s Mrs Rao thinks the orchestra and its mission are now “well appreciated and recognised”, adding: “The response we’ve got to our concerts has been very, very heart-warming and has spurred us on.”

With its reputation now firmly established, Saso has the potential to emerge as a beloved South Asian cultural icon.

The orchestra, which is currently funded entirely by Indian donors, hopes to grow with more performances at home and abroad. It also hopes to hold workshops in the region to help make symphonic music more accessible and appealing to youth, and build a stable pool of talented, trained musicians.

But for this to happen, South Asian parents, including in Singapore, will have to give up their “fear of music” as a profession that is “unstable”, said Mr Arumugam. And governments and other stakeholders must create “a vibrant enough economy” for musicians to flourish.

“The root of the problem is not so much what the families believe in or what the parents believe in, it is what the reality on the ground is. If there is no economy for musicians in Singapore, then parents will forever not send their kids to study music,” he added.