India’s vinyl revival finds its groove, mirroring global trend despite high cost

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

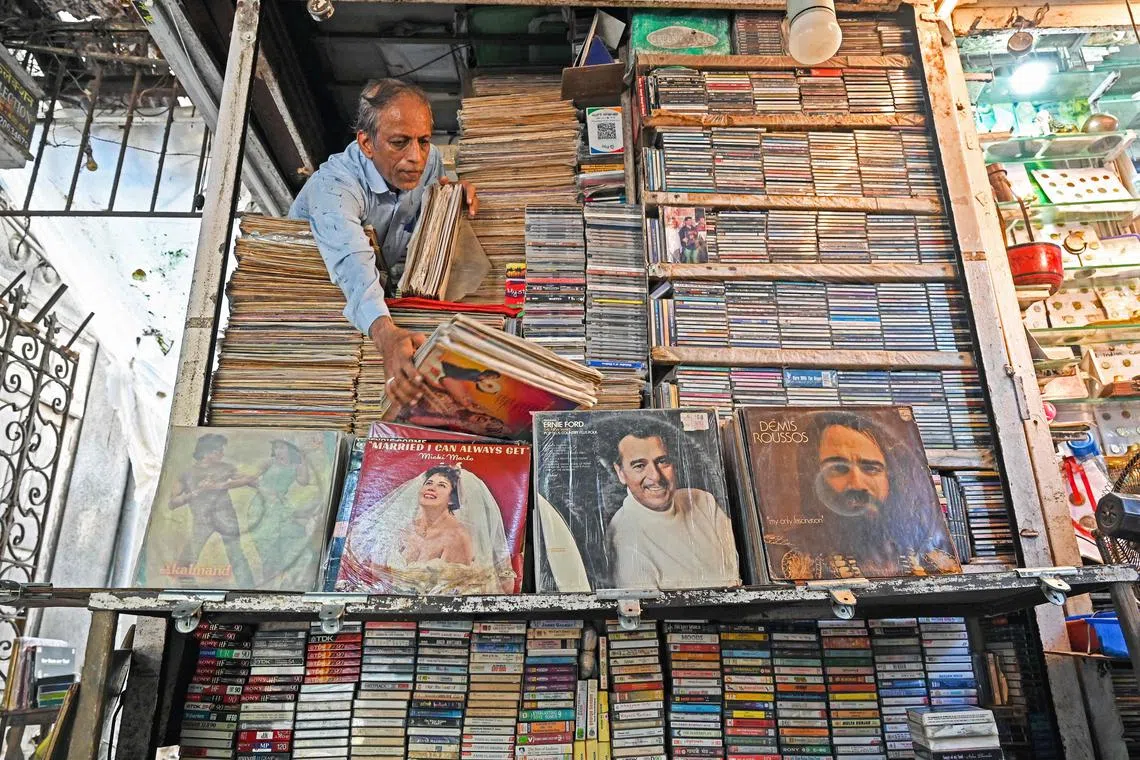

Store owner Abdul Razzak arranging vinyl records after opening his shop in Mumbai, India, on Oct 4.

PHOTO: AFP

Mumbai – Melting plastic pellets into chunky discs then squashed flat, a worker presses records in what is claimed to be the first vinyl plant to open in India in decades.

Warm music with a nostalgic crackle fills the room – a Bollywood tune from a popular Hindi movie.

“I’m like a kid in a candy shop,” grins Mr Saji Pillai, a music publishing veteran in India’s entertainment capital Mumbai, who began making pressings in August.

The revival of retro records among Indian music fans mirrors a global trend that has seen vinyl sales explode from the United States to Britain and Brazil.

Mr Pillai, 58, entered the music industry as “vinyl was just going out”.

He spent the last few years importing records from Europe for his music label clients.

But he took the decision to open his own plant – cutting import taxes and shipping times – to focus on Indian artists and market tastes from Bollywood to indie pop after recording “growing interest”.

Retailers including Walmart have embraced the retro format, and stars including Taylor Swift, Billie Eilish and Harry Styles have sent pressing plants around the world into overdrive.

In India, the scale of revival is far smaller – in part due to lower household incomes – but younger fans are now joining in the trend.

Mr Pillai admitted the industry was still “challenging” but said the market was “slowly growing”.

‘Show their love’

Vinyl record systems do not come cheap.

A decent turntable, sound system and 10 records cost fans 50,000 rupees to 100,000 rupees (S$800 to S$1,600), the lower end of which is more than double the average monthly salary.

But for those who can afford it, the old system offers a new experience.

“You go to the collection, take it out carefully... You end up paying more attention,” said 26-year-old Sachin Bhatt, a design director who grew up downloading songs.

“You hear new details, you make new mental observations... There is a ritual to it.”

Vinyl records create a “personal, tangible connection to the music we love”, he added.

“I know a lot of young kids who have vinyl, even if they don’t have a player. It’s a way for them to show their love for the music.”

Vinyl is a “completely different” experience than “shoving his AirPods” into his ears and going for a run, said 23-year-old Mihir Shah, with a collection of around 50 records.

“It makes me feel present,” he said.

Catering to these fans is a group of record stores, complementing the old records on sale in alleyway shops and flea markets.

An employee inspecting a freshly pressed vinyl record at a pressing plant in Navi Mumbai, India, on Sept 21.

PHOTO: AFP

‘Romance’

“There’s been a huge resurgence,” said Mr Jude De Souza, 36, who runs the Mumbai record store The Revolver Club, saying the growing interest dovetailed with the wider availability of audio gear and records.

Listening sessions organised by the store bring in more than 100 fans.

Despite the growth in popularity, India’s vinyl sales remain a drop in the global ocean.

While the world’s most populous country has one of the biggest bases of music listeners, with local songs racking up big views on YouTube and music streaming platforms, its publishing industry is small by global revenue standards.

Music publishing revenues hit about US$100 million (S$134 million) in the 2023 fiscal year – far smaller than Western markets – according to accountancy giant EY.

That is partly due to the lower spending power of its fans, coupled with runaway piracy.

At a small roadside store, 62-year-old Abdul Razzak is the bridge between India’s old vinyl culture and newer fans, selling up to 400 second-hand records each month to customers aged from 25 to 75.

He sells records for 550 rupees to 2,500 rupees, and believes new vinyl pressed in India will prove popular if it is priced within that bracket.

For Mr Pillai and his small factory, it provides an opportunity.

He could – if demand was there – “easily” triple the factory’s monthly production capacity of more than 30,000, something he hopes will come.

“Even though people love digital, the touch feel is not there,” he said.

“Here, there’s ownership, there’s love for it, there’s romance, there’s love, there’s life.” AFP