India's single-use plastic ban to start in July but eradication still likely long way off

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

A polluted canal in New Delhi last month.

PHOTO: AFP

Follow topic:

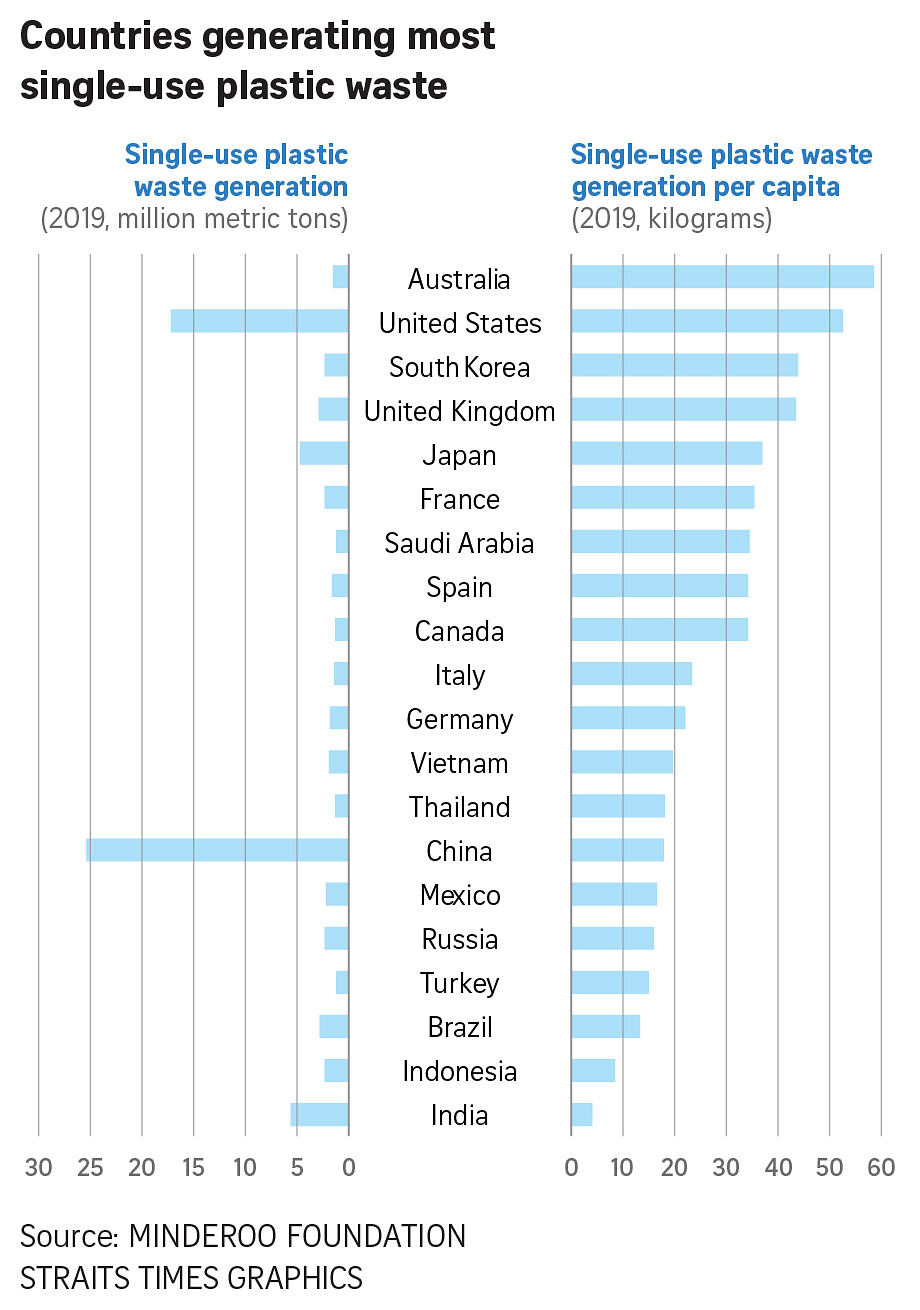

NEW DELHI - India, the world’s third-largest producer of single-use plastic waste, is taking a key step to tackle this menace that accounts for most of the plastic thrown worldwide, clogging landfills and polluting the environment.

From July 1, the country will prohibit the sale and use of a range of around 20 common single-use plastic items such as ear buds with plastic sticks, ice-cream sticks, straws, disposable cutlery and packaging film for cigarette packets, among others.

A draft of the ban was first released in March last year by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, with the final version released in August.

It had been due to start in January this year, but was delayed following opposition from the plastics industry as well as commercial users, including multinational firms.

Experts still say they do not expect the banned items to disappear entirely when the order kicks in, with enforcement and the availability of affordable alternatives being key issues that need more attention.

“Even after July 1, it is going to be a work in progress,” said Mr Siddharth Ghanshyam Singh, programme manager for municipal solid waste at the Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment, a public interest research and advocacy organisation.

“Even after July 1, it is going to be a work in progress,” said Mr Siddharth Ghanshyam Singh, programme manager for municipal solid waste at the Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment, a public interest research and advocacy organisation.

An earlier nationwide target of phasing out plastic bags less than 75 microns in thickness by the end of last September has proved unsuccessful due to poor regulation and lack of affordable alternatives.

Solid waste management is handled at the state level, and the success of this fresh ban depends on how effectively state-level authorities enforce it.

Mr Singh noted that this time, the Central Pollution Control Board has put greater weight behind the order and, for the first time, reached out to all concerned, including the state-level authorities and e-commerce portals, to make them aware of the upcoming ban.

Inspections as well as surprise checks, he added, will play a key role in enforcing the order.

Even the new July kick-in for the ban has been opposed by many from the industry who are seeking a further extension.

The Action Alliance for Recycling Beverage Cartons (AARC) – which comprises several stakeholders from the beverage industry, including firms such as Parle, Dabur, Coca-Cola and Tetra Pak – has sought an 18-month extension from July to meet the ban on single-use plastic straws.

“The time given to us has been very, very inadequate,” said its chief executive, Dr Praveen Aggarwal.

The alternative to plastic straws is either costlier paper ones or those made from “compostable” plastic, but they come with their set of challenges.

Dr Aggarwal said India currently lacks the manufacturing capacity for the straws the industry needs – food-grade paper ones with a diameter of 3mm or less.

Given the global supply crunch, he said just 10 per cent to 15 per cent of the stock needed for the next six to 12 months can be imported.

Certain AARC members have also imported a limited number of machines to make these straws, but they are not expected to be operational until next January.

Dr Aggarwal said there is a current waiting period of “more than a year” involved in purchasing these machines and commissioning them to manufacture the straws necessary in India.

The beverage industry is, meanwhile, working on producing compostable polylactic acid straws in India, but these must undergo government tests before they can be authorised for use.

“That regulatory journey of eight to 12 months has yet to happen,” Dr Aggarwal added.

India produces around 5.6 million metric tonnes of single-use plastic waste annually.

This amounts to around 4kg per person, far lower than Singapore’s 76kg that tops the world, according to The Plastic Waste Makers Index from the Minderoo Foundation.

Overall, India generates a total of around 9.46 million tonnes of plastic waste a year, of which around 60 per cent is collected and recycled. The rest goes to landfills and litters the environment.

The prohibition order does not extend to plastic food packaging that accounts for almost 60 per cent of India’s plastic waste, such as multi-layer packaging used for chips.

It also freezes the list of single-use plastic items to be phased out for the next 10 years.

“That is a very big problem,” he said. “It should be the other way around... Every couple of years, we should keep identifying problematic plastics and give the industry a good amount of time so that they invest in R&D around materials used for packaging and not just the product and find alternatives.”

The impending ban has drawn greater focus on the lack of affordable alternatives to plastic.

Ms Shruti Sinha, manager for policy and outreach at Chintan Environmental Research and Action Group, said there is a need for “mass investment on entrepreneurship around alternatives to plastic”.

“One of the biggest challenges around plastic is the lack of alternatives and what happens to small producers who have been making a living out of this. Just transitions are crucial to prevent livelihood loss,” she told ST.