Indian government turns to crowdsourcing to treat patients with rare diseases

Sign up now: Get ST's newsletters delivered to your inbox

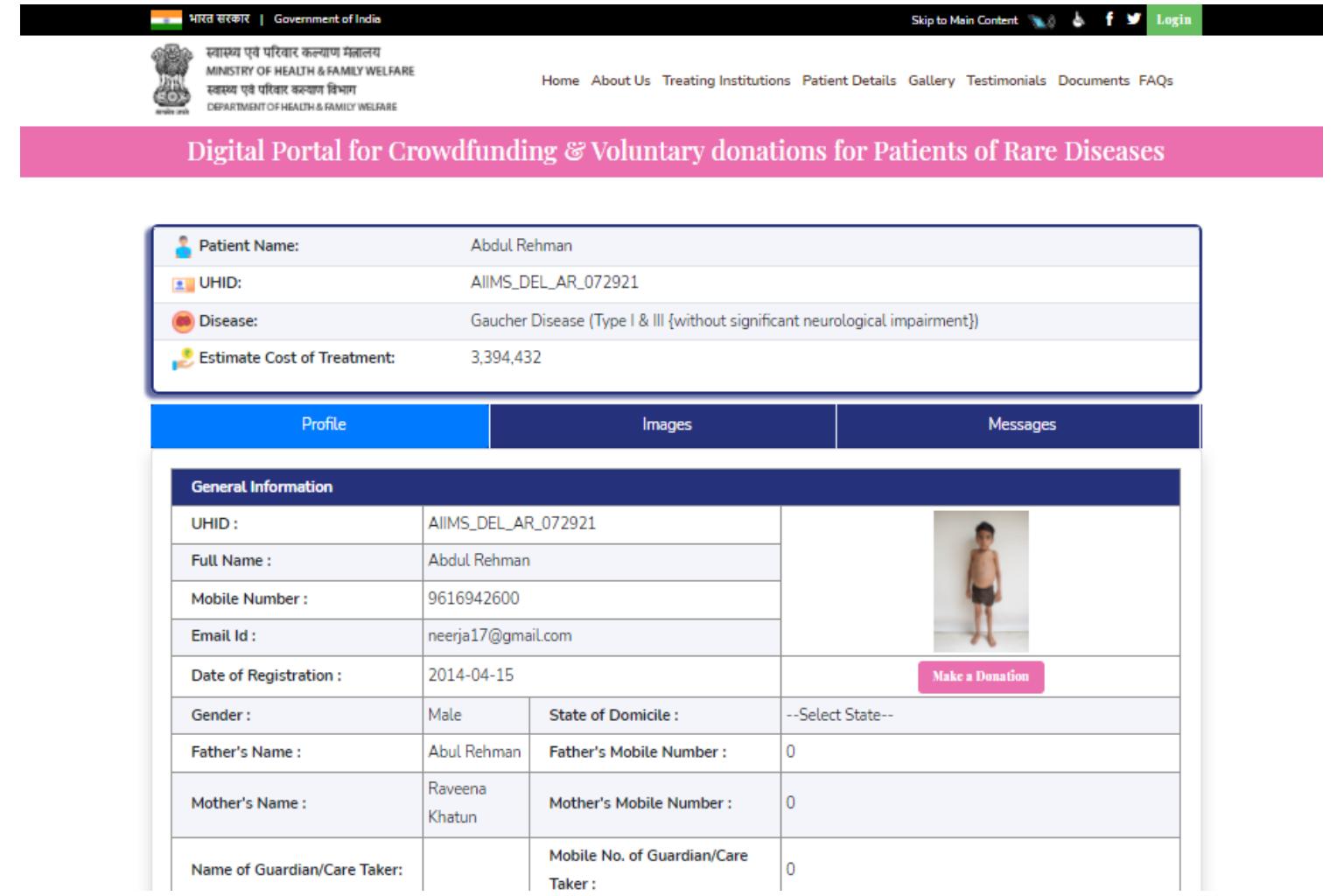

Patient Abdul Rehman is one of the potential beneficiaries of an unprecedented Indian government initiative.

PHOTO: SCREENGRAB FROM RAREDISEASES.NHP.GOV.IN

Follow topic:

NEW DELHI - Seven-year-old Abdul Rehman is one of the first potential beneficiaries of an unprecedented Indian government initiative to crowdsource donations for treatment of patients suffering from rare diseases.

"Please donate to Abdul Rehman," tweeted India's Ministry of Health and Family Welfare on Aug 11, adding a link to a page about him on a dedicated government portal set up to gather donations for patients such as him.

Abdul suffers from Gaucher disease, a rare genetic disorder that causes lipids to accumulate in certain organs such the spleen or liver. An enzyme-infusion therapy to break down these lipids costs around 3.4 million rupees (S$62,000) each year for his family, which is beyond its reach.

It now also seems to be beyond the reach of the Indian government, prompting the creation of the crowdfunding portal - a decision the government has justified "in view of the high cost of treatment, resource constraints and competing health priorities".

The move has raised concerns from such patients' parents who feel the state has abdicated its responsibility in assuring treatment for their loved ones.

The portal, which went live in the last week of July, has yet to be formally launched. It has 31 registered patients and has received more than 58,500 donations; the exact amount received has not been revealed.

There are more than 7,000 diseases classified as rare, most of them with a genetic basis.

The World Health Organisation estimates around one out of 15 persons worldwide could be affected by such a rare disease. Given India's large population, this means more than 70 million may be affected by these rare ailments.

The portal is part of a new government policy for rare diseases that was approved in March, after a court ordered the central government to finalise its policy to facilitate treatment for such diseases.

Under this national policy, rare diseases have been categorised into three groups.

Diseases in the first group involve a one-time curative treatment. Patients below the poverty line and those from other economically weak backgrounds will be eligible for a one-time support of up to two million rupees from the central government.

In the second group of diseases, involving those who require lifelong treatment but not extensive financial support, the policy recommends that states "consider" supporting such patients. State governments have stepped in to help treat patients with rare disorders, but usually after being prodded by courts and campaigns by affected families.

The third group comprises diseases that have definitive treatment but involve a very high cost and lifelong therapy.

Donations are currently being sought for these patients and there is no mention of assured government funding for patients of the second and third groups in the new policy.

"Literally, if you look at it, parents like me in the middle class have no commitment for treatment or long-term supportive care or diagnostics from the government; nothing," said Mr Prasanna Kumar Shirol, the founder of Organisation for Rare Diseases India, which represents the interests of families with patients of rare disorders.

Crowdfunding cannot be a solution for treatment of rare diseases without any funding commitment from the government, he told The Straits Times. "Even if you are lucky to get funding in the first year, how do you ensure that every year that child gets uninterrupted treatment through crowdfunding?"

Acknowledging the high cost involved in treating all patients of rare diseases, Mr Shirol suggested the government at least make a start by committing a certain sum of money to the cause and raise additional funds through other means such as a special tax for rare diseases and donations through corporate social responsibility.

Many parents have already been crowdfunding through private portals, such as Ketto and Milaap, to finance treatment of their children.

Dr Meenakshi Bhat, a clinical geneticist and a faculty member at Bangalore's Centre for Human Genetics, told ST crowdfunding needs to be viewed as one of the sources of financing treatment of rare disorders, given the large number of such patients in India and the exorbitantly high cost of treating these disorders.

"I feel our sheer number is what is possibly a discouragement, if not a deterrent, for the government to allocate all the money for treatment of patients of rare disorders, especially because we don't know what the long-term outcome will be," said Dr Bhat, who has dealt with around 45,000 patients of rare genetic disorders in her 15-year record of examining such patients.

For example, a one-time gene therapy for spinal muscular atrophy, a rare inherited genetic neuromuscular disease, costs around 160 million rupees.

Only about 500 of the 7,000-odd rare diseases have treatments available. Moreover, there are certain disorders with a very high cost of treatment but for which there is still inadequate scientific evidence to establish good long-term treatment outcomes.

Dr Bhat said she hopes the central government would be able to use its heft to crowdfund a significant sum through the portal to facilitate a substantial intervention in treating rare disorders.

A government official involved with the project, who did not wish to be identified, told ST the government is working on measures to induce donations, including offering tax incentives to donors.