India’s exit poll industry faces biggest credibility test after record election

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

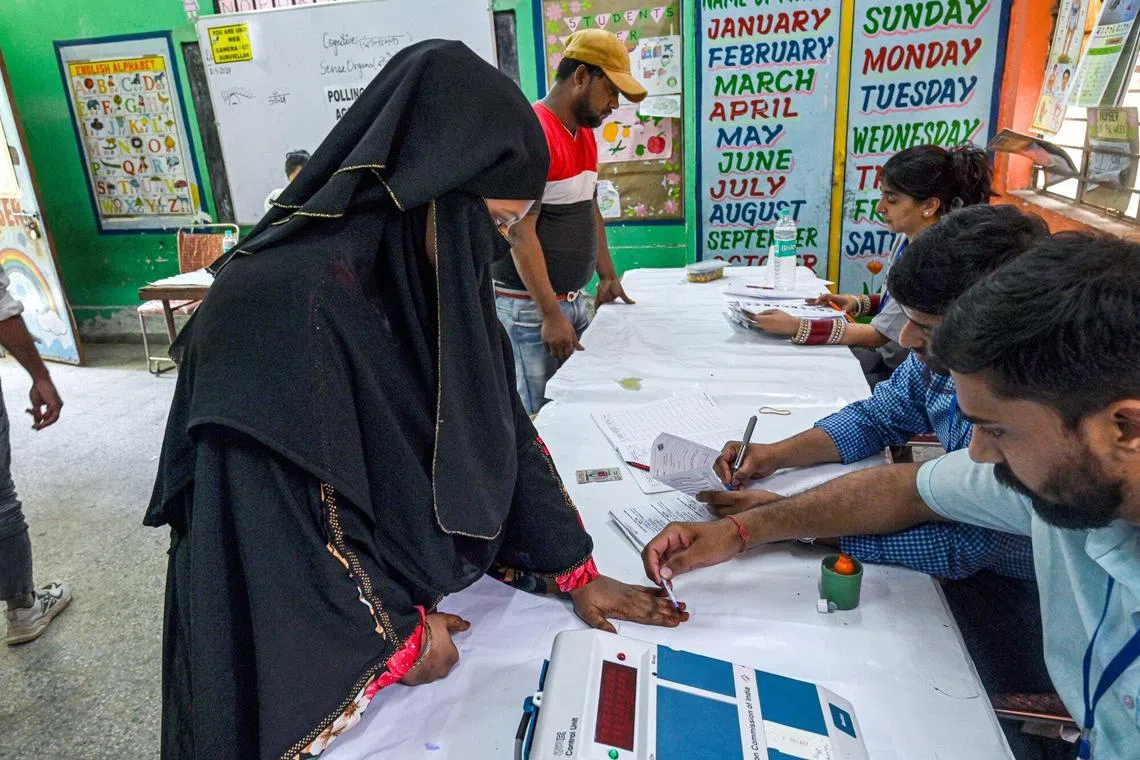

Since April 19, Indians have been voting in national parliamentary elections in a seven-phase election for 543 constituencies.

PHOTO: BLOOMBERG

Follow topic:

BENGALURU – As the last phase of India’s marathon election concludes on June 1, think-tanks and polling agencies are preparing to release a flurry of exit poll results to try to project the winner and the extent of the victory.

Exit polls, conducted immediately after voting ends, are the penultimate spectacle before the Election Commission announces the results on June 4.

This election – the largest in India’s history

“You may ask, why spend time and money on exit polls when results are (out) in just three days, but the fact is that across the world, there is huge interest in knowing who might be winning before we know who has won,” said Mr Rajdeep Sardesai, a senior anchor at English news channel India Today.

At least a dozen organisations have been conducting exit polls to understand voter behaviour and choices in the world’s largest democracy.

Since April 19, Indians have been voting in national parliamentary elections in a seven-phase election for 543 constituencies. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is seeking a third term in the Lok Sabha, or Lower House of Parliament.

While pre-poll surveys showed Mr Modi remains popular,

While voting is under way, India’s Election Commission does not allow exit polls to be conducted, and their results published or publicised. So pollsters begin their work 30 minutes after the last vote is cast in every phase across the country.

After each phase, exit pollsters ask voters which political party they supported. Some also conduct opinion polls before the elections, as well as a post-poll survey, done a few days after each voting phase.

The final tally can be announced only after the last voting day.

Polling fever reached epidemic proportions in 2024 because nearly a billion voters are casting their ballots in the election, with a record 744 political parties and 8,360 candidates contesting.

In addition, because the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) won nearly all the seats in many states in the previous election in 2019, pollsters are seeing it as the Modi government’s election to lose.

Predicting election outcomes in a chaotic, diverse and unpredictable country like India is risky business. So exit polls do get it wrong.

Voters wait in line at a polling station during the sixth phase of voting for national elections in Delhi, on May 25.

PHOTO: BLOOMBERG

During the 2004 election, all exit polls predicted a comfortable victory for the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance, but Congress eventually emerged as the single largest party in the Lok Sabha.

In the exit polls of 2014, most polls predicted the winner correctly, but failed to assess the extent of the BJP’s victory.

Mr V.K. Bajaj, co-founder of Today’s Chanakya, a Delhi-based polling agency, said: “India is very complex – each state is like a country. All factors that influence voting change by region, caste, gender, age, phase of election, promises made by candidates, local history, and now, more than ever, what people see on social media.”

Voter behaviour has been “harder than ever to predict”, he added, as people refuse to divulge their preference to pollsters or mislead them out of suspicion, fear and a growing sense of privacy.

Polling organisations often tie up with the media organisations that also sponsor them. The day after polling ends – sometimes on the same night – news channels and newspapers announce their exit poll numbers in large font.

Mr Yashwant Deshmukh, founder of pollster C-Voter International, said that in recent years, television channels competed to be the earliest to announce exit poll results, or predict the number of seats, “but these are the dumbest ways to use exit polls”.

“Statistically, exit polling only allows you to project the share of votes each party will get, along with some detail about how people across demographics vote on certain issues. Predicting seats is a mathematical extrapolation that is not the purpose of exit polls,” he added.

More than seat projections, he said “the details in the exit polls are supposed to help us understand how the winners won, and why people voted the way they did”.

Mr Bajaj, whose polling firm Today’s Chanakya was the only one to predict the magnitude of the BJP’s victory in 2014 with great accuracy, dismissed such criticism.

“Vote share is important for a research organisation. But a common individual only cares who is going to rule the country, and how many seats they will win,” he said.

While Today’s Chanakya does not publicly share its sample size or methodology, Mr Bajaj said that its approach is interviewing the right voters, “by creating a sample, even if small, that is truly representative of caste equations, rural and urban balance, gender, age range and some regional parameters”.

Mumbai-based Axis My India, on the other hand, depends on an enormous sample. Established 10 years ago, it is also among the few Indian polling agencies to publish its methodology, which its media partner India Today carries on its website.

In 2019, Axis My India conducted face-to-face interviews with 742,187 respondents in nearly all parliamentary seats. In 2024, 1,500 surveyors will poll voters in more than 3,500 assembly constituencies that fall in the parliamentary seats, accounting for over 30,000 villages.

Employees crunch numbers at Axis My India’s Mumbai office before the polling agency releases its exit polls.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF AXIS MY INDIA

Mr Pradeep Gupta, managing director of Axis My India, which is also commissioned by political parties including the BJP, said: “We ask voters wholesome questions about social indicators, visibility of legislators, government schemes, and then ask who they voted for.”

Mr Gupta is known to break into a dance on news channels when his firm’s exit polls get it right, such as when it forecast the exact vote shares that led the BJP to win a second term in 2019.

For their “physical exertions and patience for voters rejecting them”, Mr Gupta said the six-member survey teams that correctly predicted each seat got rewards, such as a night’s stay at a five-star hotel, 500 rupees (S$8) each and meetings with celebrities.

“India loves cricket, Bollywood and elections, but it is only an election that affects all lives. To get close to understanding how Indians vote is a big thrill,” he said.

Concerned that “most exit polls have lost their rigour as they are driven by market pressures, rather than serious, academic, deep-rooted analysis”, Mr Sardesai called for greater regulation and disclosure of methodology and conflict of interest to eliminate “fly-by-night polling agencies”.

He added that in the past, some pollsters faced pressure from TV channels or political parties to “tone down” any projections that the ruling party is losing, “to avoid antagonising them, in case the forecast is wrong”.

“We need a statutory warning in this numbers game: Too many exit polls are injurious to health.”