Who should run KL? Study into local poll stirs fears over demographics

Sign up now: Get insights on the biggest stories in Malaysia

Since 1974, the city has been administered by the Kuala Lumpur City Hall, while led by a mayor appointed by the Federal Territories Minister with the consent of the King.

PHOTO: BERNAMA

- A government study explores electing Kuala Lumpur's mayor, reviving a sensitive debate over federal control versus residents' say in city governance.

- Malay-Muslim groups fear mayoral elections could weaken Malay political influence and federal control due to Kuala Lumpur's diverse demographics and voting patterns.

- Proponents argue electing a mayor addresses Kuala Lumpur's "democratic deficit" providing accountability and direct representation for residents in city administration.

AI generated

KUALA LUMPUR – In most democracies, choosing the mayor of a capital city is routine. But in Malaysia, reintroducing local elections

A new government-commissioned feasibility study into electing Kuala Lumpur’s mayor has revived a long-running debate over who should control the country’s political and economic nerve centre: the federal government, or the city’s two million residents.

The fight over electing KL’s mayor isn’t just about local politics – it’s about whether Malaysia’s most ethnically mixed city can balance democratic representation with the delicate power-sharing between races that has shaped the country for decades. The debate reveals deeper fears about who controls urban centres and whether ethnic demographics should decide who runs a modern capital.

“Introducing a mayoral election in this situation could lead to voting based on racial sentiment, where the larger group dominates the smaller one,” Mr Mohd Zai Mustafa, chairman of hardline Malay-Muslim coalition Gerakan Pembela Ummah, told The Straits Times.

He warned that a direct vote could affect ethnic harmony and reduce Malay influence in the Federal Territory, handing control towards the community which they claim have already dominated its wealth.

Mr Zai also argued that KL’s administration requires close coordination with the federal government, as it houses foreign embassies, the national palace, and key federal agencies. An elected mayor, he argued, could complicate policy alignment and development planning.

Federal Territories Minister Hannah Yeoh previously said the study, conducted by the International Islamic University of Malaysia (IIUM), is merely examining the legal and practical implications of introducing a mayoral election.

The proposal has drawn political attention partly because the Chinese-led Democratic Action Party (DAP), a key component of the ruling coalition that has long backed restoring local government elections, has performed strongly in urban constituencies such as KL.

“There is no need to worry, this study is not carried out by DAP members. It is by IIUM, and I am confident in the quality of their research,” Ms Yeoh told reporters on Feb 3.

No vote, no voice

The sensitivity partly stems from KL’s constitutional position, since its governance has a unique “democratic deficit”. While most Malaysians vote for federal and state representatives, KL has no state legislative assembly.

Since 1974, the city has been administered by the Kuala Lumpur City Hall, while led by a mayor appointed by the Federal Territories Minister with the consent of the King.

Residents have a say in who sits in the Parliament, but zero say on who runs their own streets, manages their nearly RM3 billion (S$975 million) annual budget, or approves the skyscrapers changing their skyline. Electing a mayor would alter that arrangement.

Local government elections in Malaysia were suspended in 1965 under the Emergency (Suspension of Local Government Elections) Regulations during the Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation, when the federal government invoked emergency powers amid security concerns and political tensions. Although local councils had previously been elected, the suspension halted municipal polls nationwide, and elected bodies were gradually replaced with appointed administrators and temporary boards in the years that followed.

Rather than restoring elections after the emergency period, Parliament entrenched the change through the Local Government Act 1976, which abolished the legal basis for local government elections and formalised a system of appointed councillors. Since then, local authorities have remained appointed by state government or the federal government in the Federal Territories, with successive administrations citing administrative, legal and political considerations for not reinstating local polls.

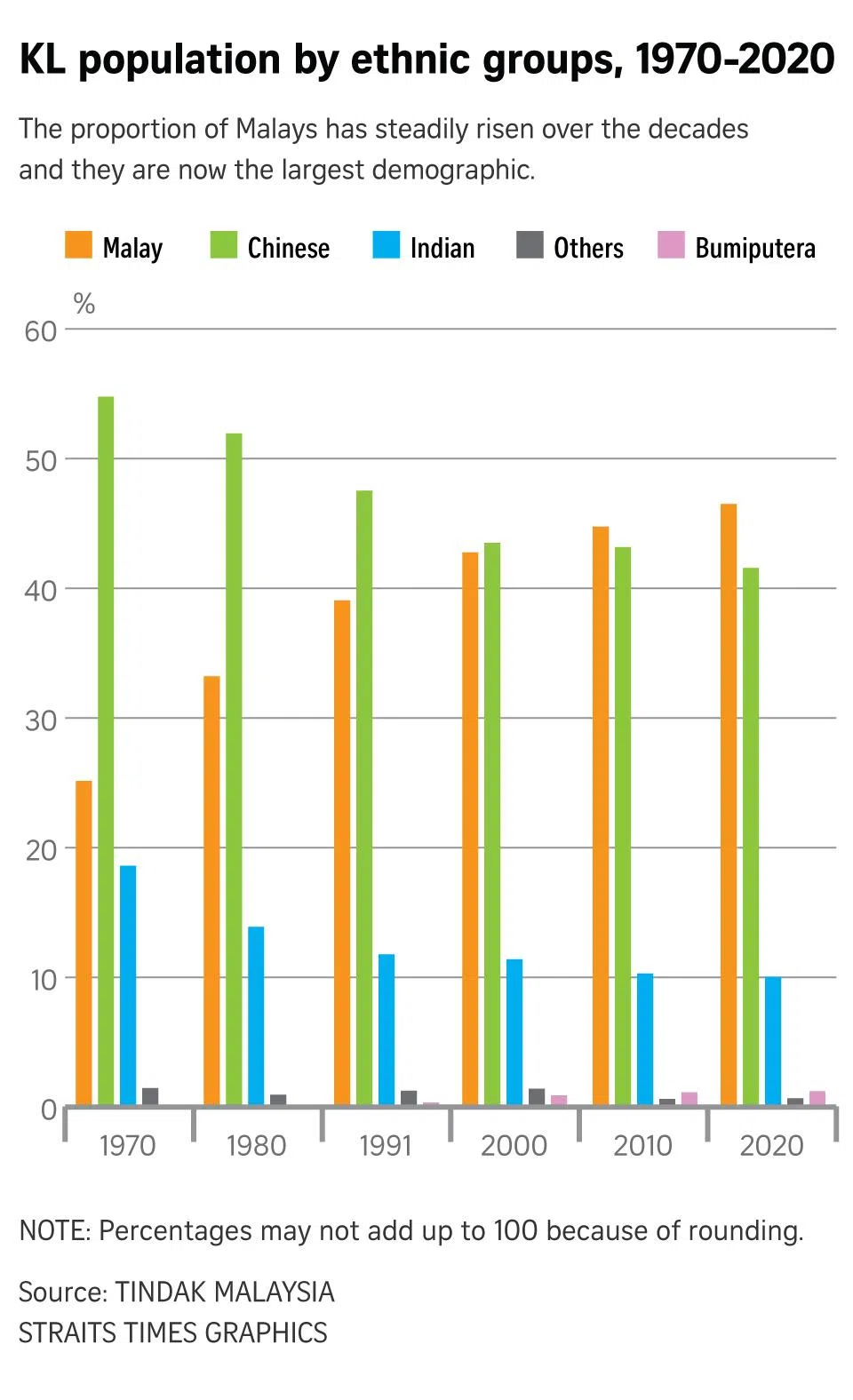

Demographics sharpen the debate. According to the Department of Statistics Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur had about a population of 2.1 million in 2025 based on mid-year estimates.

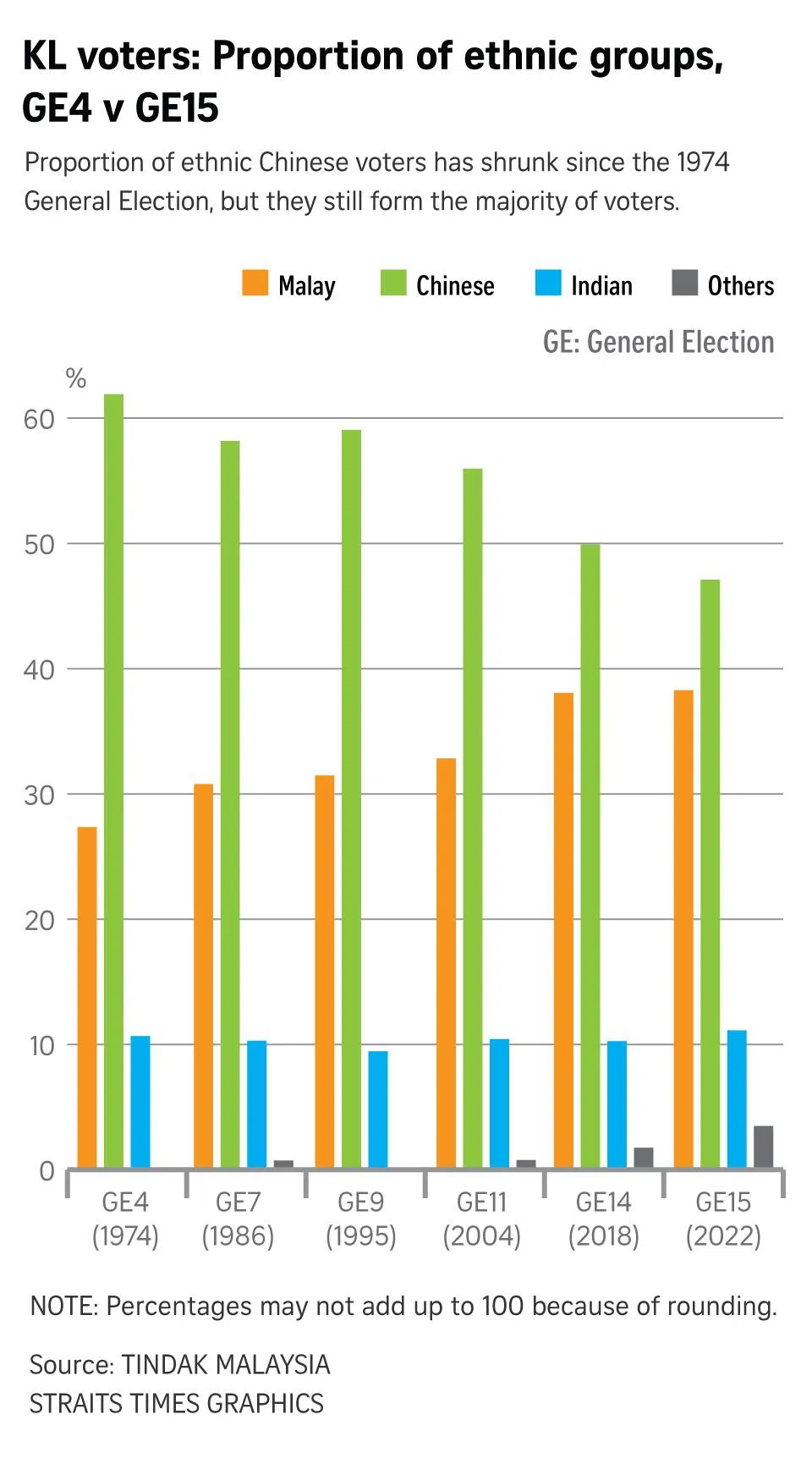

Government data showed 47.7 per cent Malay or other Bumiputera, 41.6 per cent Chinese, 10 per cent Indian and 0.7 per cent others. Malays do not form an outright majority. Non-Malay communities together account for slightly more than half of the population.

The political backdrop helps explain the anxiety. In the 2022 general election, the DAP won five of KL’s parliamentary seats, largely in commercial and inner-city constituencies where Chinese voters were concentrated.

Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s party, Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR), also won five seats, in Malay-majority residential areas and government-linked communities in the fringes of the city. UMNO won one seat, while opposition bloc Perikatan Nasional secured two. The results reflect the city’s geography.

Learning from neighbours

Constitutional scholar Professor Shad Saleem Faruqi, former holder of University Malaya’s Tunku Abdul Rahman chair, acknowledged these concerns but said Malaysia should not avoid discussing local elections.

He noted that local government elections were suspended in the 1960s and later abolished in 1976, and that any reintroduction would require legal changes.

Datuk Shad suggested that if reform is considered, Malaysia could study systems such as Singapore’s group representation constituency (GRC), where teams of candidates are elected together to reflect the diversity of a community. Such an approach, he said, may help ensure diverse representation in urban areas.

“This is not only about ethnicity. It is about making sure the needs of people living in Kuala Lumpur are properly represented,” he told ST.

Danesh Prakash Chacko, chairperson of Persatuan Bertindak Pilihan Raya Bebas Dan Saksama (Tindak) an electoral reform group, said local elections need not mirror the electoral system used at federal or state level and could be designed to reflect KL’s demographic realities.

“The fear that one ethnic group will take over the city is increasingly outdated, misplaced and increasingly losing steam,” he said adding that elected councils would be directly answerable to the voters for any decision making process.

Mr Amirul Ruslan, a KL-based urbanist, said electing a mayor would bring visibility and accountability to a city administration that currently operates largely out of public view, with residents having no direct say in choosing its leadership.

“Even if key powers remain with the federal government, having a mayor that voters choose would give a clear face and name to the city’s direction,” he told ST.

He pointed to the departure of former mayor Maimunah Mohd Sharif

“The way she was moved to another role felt opaque and underscores why direct elections would matter,” said Mr Amirul.

But for some residents, the issue is straightforward.

Chatting to ST at a coffee shop in the city Mr Barry Tan, 46, who runs a tyre shop in Sentul, said leadership ability matters more than race.

“Change is good. Race is not the issue as long as the person is capable of leading Kuala Lumpur,” he said.

Sign up for our weekly

Asian Insider Malaysia Edition

newsletter to make sense of the big stories in Malaysia.