What’s behind powerful earthquake in Myanmar

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

Rescue personnel at work at the site of a building that collapsed after a strong earthquake struck central Myanmar.

PHOTO: REUTERS

SINGAPORE – A powerful earthquake of magnitude 7.7 centred in the Sagaing region near the Myanmar city of Mandalay caused extensive damage in that country

How vulnerable is Myanmar to earthquakes?

The country lies on the boundary between two tectonic plates and is one of the world's most seismically active places, although large and destructive earthquakes have been relatively rare in the Sagaing region.

“The plate boundary between the India Plate and Eurasia Plate runs approximately north-south, cutting through the middle of the country,” said Professor Joanna Faure Walker, an earthquake expert at University College London (UCL).

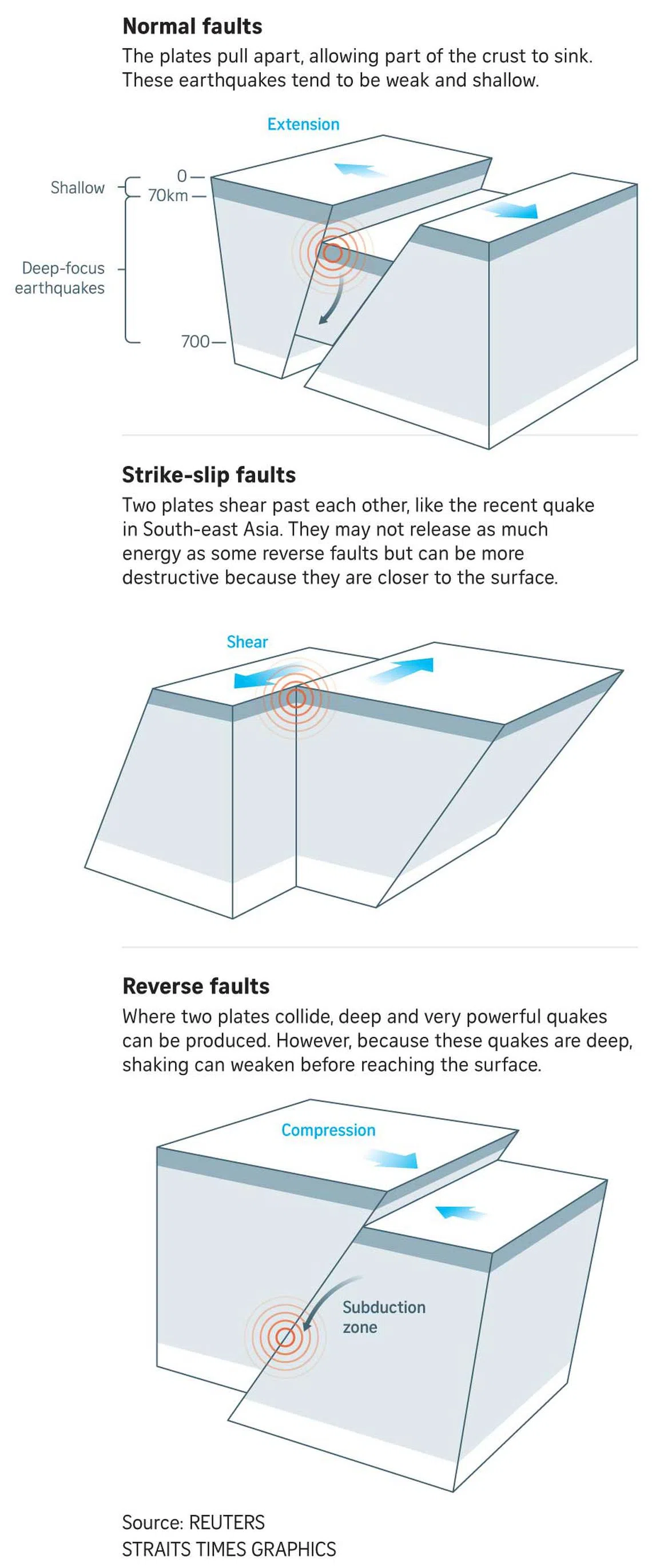

She added that the plates move past each other horizontally at different speeds. While this causes “strike slip” quakes that are normally less powerful than those seen in “subduction zones” like Sumatra, where one plate slides under another, they can still reach magnitudes of 7 to 8.

Why was the March 28 earthquake so damaging?

Sagaing has been hit by several quakes in recent years, with a 6.8-magnitude event causing at least 26 deaths and dozens of injuries in late 2012.

But the March 28 event was probably the biggest to hit Myanmar’s mainland in three quarters of a century, said Professor Bill McGuire, another earthquake expert at UCL.

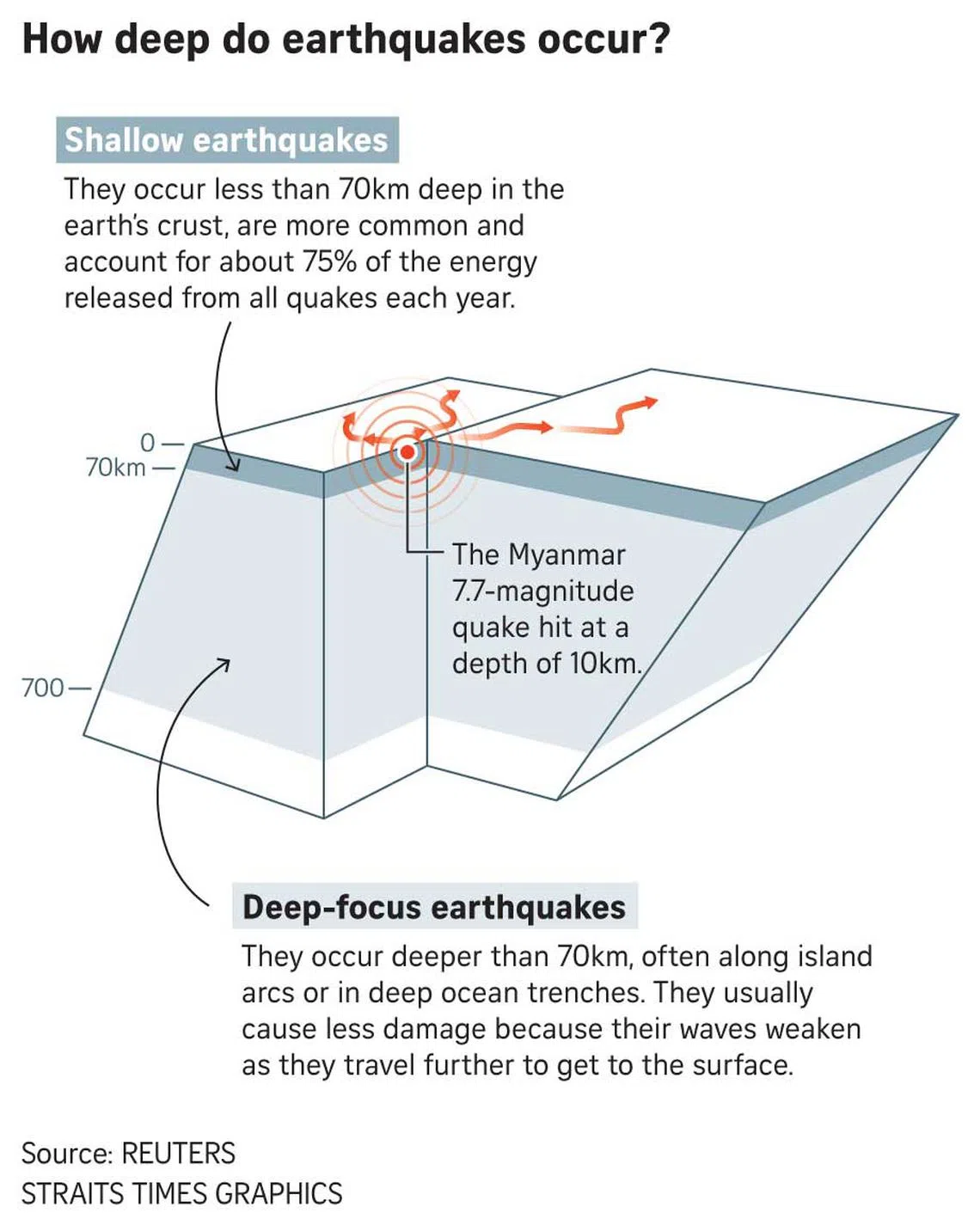

Dr Roger Musson, honorary research fellow at the British Geological Survey (BGS), said the shallow depth of the quake meant the damage would be more severe. The quake’s epicentre was at a depth of just 10km, according to the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

“This is very damaging because it has occurred at a shallow depth, so the shock waves are not dissipated as they go from the focus of the earthquake up to the surface. The buildings received the full force of the shaking.”

“It’s important not to be focused on epicentres because the seismic waves don’t radiate out from the epicentre – they radiate out from the whole line of the fault,” he added.

Dr Rebecca Bell, a tectonics expert at Imperial College London, suggested it was a side-to-side “strike-slip” of the Sagaing fault.

This is where the Indian tectonic plate, to the west, meets the Sunda plate that forms much of South-east Asia – a fault similar in scale and movement to the San Andreas fault in California.

“The Sagaing fault is very long, 1,200km, and very straight,” Dr Bell said. “The straight nature means earthquakes can rupture over large areas – and the larger the area of the fault that slips, the larger the earthquake.”

How prepared was Myanmar?

It has been hit by powerful quakes in the past.

There have been more than 14 earthquakes with a magnitude of 6 or above in the past century, including one near Mandalay in 1956, said Dr Brian Baptie, a seismologist with the BGS.

The USGS Earthquake Hazards Programme said on March 28 that fatalities could be between 10,000 and 100,000 people, and the economic impact could be as high as 70 per cent of Myanmar’s gross domestic product.

Dr Musson said such forecasts are based on data from past earthquakes and on Myanmar’s size, location and overall quake readiness.

The relative rarity of large seismic events in the Sagaing region – which is close to heavily populated Mandalay – means that infrastructure had not been built to withstand them. That means the damage could end up being far worse.

“Most of the seismicity in Myanmar is farther to the west whereas this is running down the centre of the country,” he noted.

Dr Ian Watkinson, from the department of earth sciences at Royal Holloway University of London, said what had changed in recent decades was the “boom in high-rise buildings constructed from reinforced concrete”.

Myanmar has been riven by years of conflict and there is a low level of building design enforcement.

“Critically, during all previous 7-magnitude or larger earthquakes along the Sagaing fault, Myanmar was relatively undeveloped, with mostly low-rise timber-framed buildings and brick-built religious monuments,” he added.

“Today’s earthquake is the first test of modern Myanmar’s infrastructure against a large, shallow-focus earthquake close to its major cities.”

Dr Baptie said at least 2.8 million people in Myanmar were in hard-hit areas where most lived in buildings “constructed from timber and unreinforced brick masonry” that are vulnerable to earthquake shaking.

Dr Ilan Kelman, an expert in disaster reduction at UCL, said: “The usual mantra is that ‘earthquakes don’t kill people; collapsing infrastructure does’.”

“Governments are responsible for planning regulations and building codes. This disaster exposes what governments of Myanmar failed to do long before the earthquake, which would have saved lives during the shaking.” REUTERS, AFP