So near yet so far: Sabah grapples with water woes ahead of election

Sign up now: Get insights on the biggest stories in Malaysia

Kunak community leader Chong Pak Kong said blue plastic tanks have become essential to overcome low water pressure.

ST PHOTO: LU WEI HOONG

- Sabah faces a chronic water shortage with only 80.5% access to treated water, lower than other Malaysian regions, worsened by infrastructure collapse.

- Many Sabah residents, like Rosimah, rely on expensive treated water or collect rainwater, while E. coli levels in treated water exceed safety limits.

- The Sabah government plans to corporatise the Water Department and start new projects, aiming to resolve water issues by 2050; Warisan suggests importing water.

AI generated

SEMPORNA/KUNAK, Sabah – Flushing the toilet after answering nature’s call is often taken for granted.

But in Semporna, a popular seaside resort town often dubbed the “Maldives of Malaysia”, this Straits Times correspondent found himself scrambling for water after being greeted with a dry tap and a “No Water” notice.

Such incidents are not isolated. Water shortages are a chronic problem plaguing Sabah.

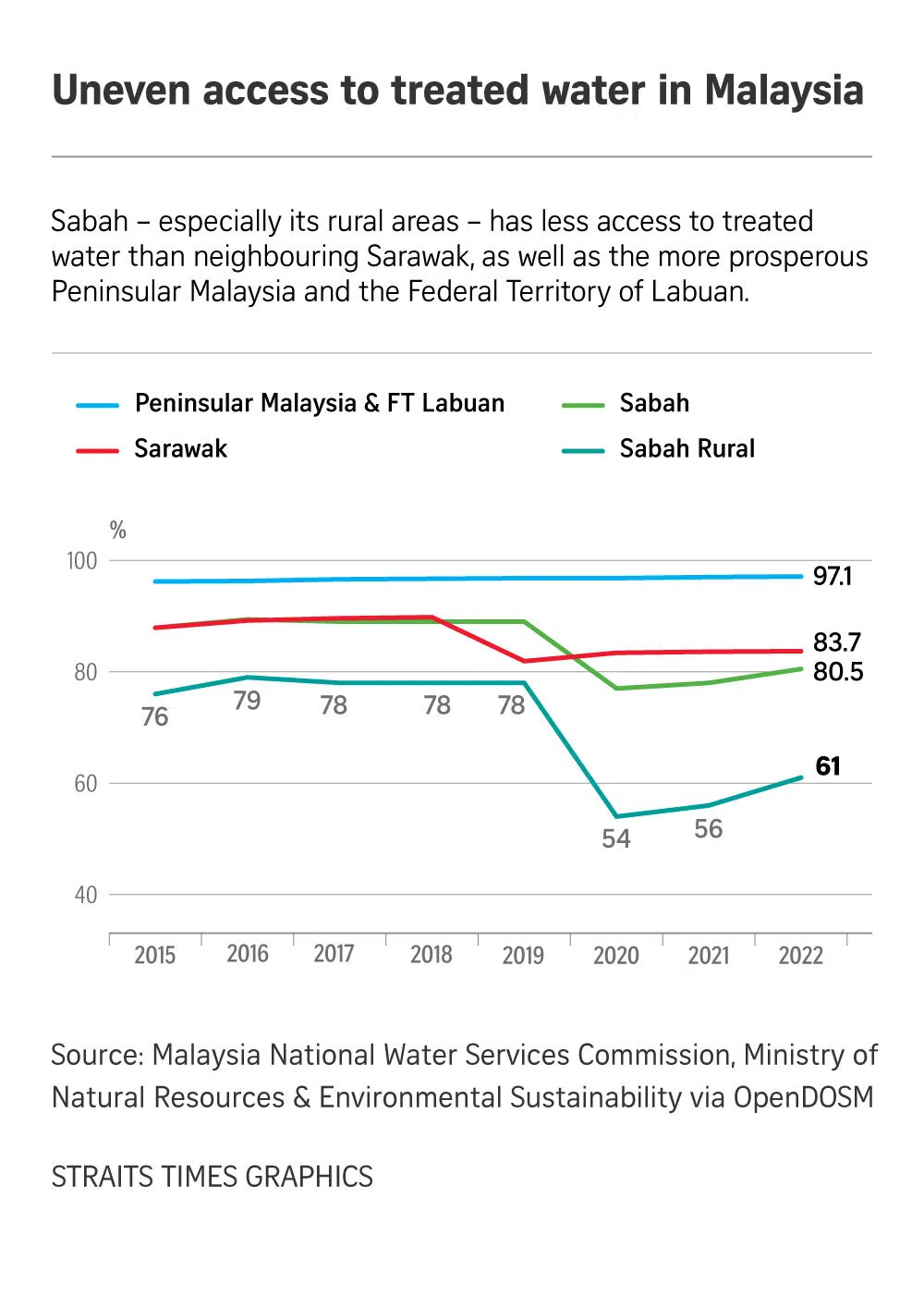

The second-largest state in Malaysia has the lowest access to treated water, at 80.5 per cent of households in 2022.

In neighbouring Sarawak, 83.7 per cent of households are connected to the piped water network, while the figure in Peninsular Malaysia along with the Federal Territory of Labuan stands at 97.1 per cent.

Worse still, a landslide in mid-September caused the collapse of a transmission tower in central Sabah, knocking out the power supply – including that of water treatment plants. This has exposed a deep structural vulnerability in the state’s water infrastructure.

Public anger over the crisis forced Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim to pledge to resolve the so-called “AJK issues” – air (water), jalan (roads) and karan (electric current in local slang) – on Nov 9, just weeks before the Sabah election on No v 29.

Administrative clerk Rosimah Mohd Amin, 33, lamented that her home in Blok Tarapuli, a hilly suburb 20km from Semporna, remains off the Sabah water supply grid.

Her family of 12 lives about 1.5km from the nearest water pipe and 900m from the closest river – so near, yet so far.

“We are forced to buy treated water for RM45 (S$14.20) to fill a 560-litre tank, which lasts only two or three days,” the mother of three told ST.

If Ms Rosimah were connected to the water grid, she would pay only around 15 Malaysian sen under the Sabah Water Department’s domestic rate – a 300-fold difference.

During the monsoon season, the family saves money by relying in part on rainwater collected in a blue plastic tank, commonly seen in Sabah households in varying sizes. However, the water collected in their 909-litre tank rarely lasts more than a week.

Another option for Ms Rosimah is to use well water, but the mineral-rich groundwater is suitable only for washing clothes and bathing.

“It can’t be used for cooking as the rice would turn green (when cooked),” she said.

Sabah’s 89 water treatment plants have a total capacity of 1,400 million litres of water per day (MLD). But demand has reached 1,600 MLD – a shortfall of 200 MLD – the state’s Deputy Chief Minister and Works Minister Shahelmey Yahya said in January 2024.

The electric water pump is a common feature in commercial shop lots along Sabah’s East Coast, where water disruptions are frequent.

ST PHOTO: LU WEI HOONG

Making matters worse, 57 per cent of treated water is currently lost before reaching consumers, either through leaking underground pipes or theft via illegal connections supplying squatter settlements and construction sites.

The average across states in Peninsular Malaysia is 32 per cent.

In Sabah, cartons of plastic bottled water can often be found stacked in front of sundry shops.

ST also observed Sabah’s east coast residents queueing day and night to refill containers at vending machines dispensing drinking water across town, a lifeline for those without reliable water access.

Yet, the quality of this treated water falls below the national minimum standard.

Cartons of bottled water displayed at the entrance of a petrol station in a town in Sabah East Coast.

ST PHOTO: LU WEI HOONG

According to the Malaysia Auditor-General’s Report 2/2024, E. coli levels in Sabah’s treated water hit 2.35 per cent – 16 times higher than the permissible limit of 0.15 per cent. The bacteria can cause abdominal cramps and diarrhoea.

Even for households connected to the water grid, supply is far from consistent.

In Kunak, a transport hub about 60km north of Semporna, shoplots and residential areas receive water only twice a day, for up to two hours in the morning and again in the evening. The taps stay dry for the rest of the day as treatment plants cannot keep up with demand.

Local community leader Chong Pak Kong, 69, said an electric pump is essential to overcome low water pressure. “I have five 400-litre water tanks, and I still don’t know if they’ll ever be full. It was even worse three years ago – I used to get less than an hour of water supply per session,” he said.

Mr Chong credited Gabungan Rakyat Sabah (GRS) assemblywoman Norazlinah Arif for “banging the table” at the Sabah Water Department to push for better service quality. GRS is the senior partner in the caretaker Sabah government coalition.

To address Sabah’s chronic water woes, caretaker Chief Minister and GRS chief Hajiji Noor announced in September a plan to corporatise the Sabah Water Department to improve efficiency and add 18 new water supply projects to raise overall capacity.

His deputy, Mr Shahelmey, estimated that the Sabah water woes could be resolved by at least 2050.

Opposition party Warisan has promised a new water dam in Lahad Datu, about 140km north-west of Semporna, should it form the state government.

The dam, potentially serving both hydroelectric power and water supply needs, would be a long-term project designed to meet the growing demand along Sabah’s east coast, including Semporna, Tawau and Lahad Datu.

“In the short term, we may consider importing water from neighbouring Sarawak, which has a surplus from the Bakun Dam,” incumbent Warisan assemblyman Jamil Hamzah told ST.

Sign up for our weekly

Asian Insider Malaysia Edition

newsletter to make sense of the big stories in Malaysia.