Outspoken Laos lawmaker’s election exit sparks rare dissent

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

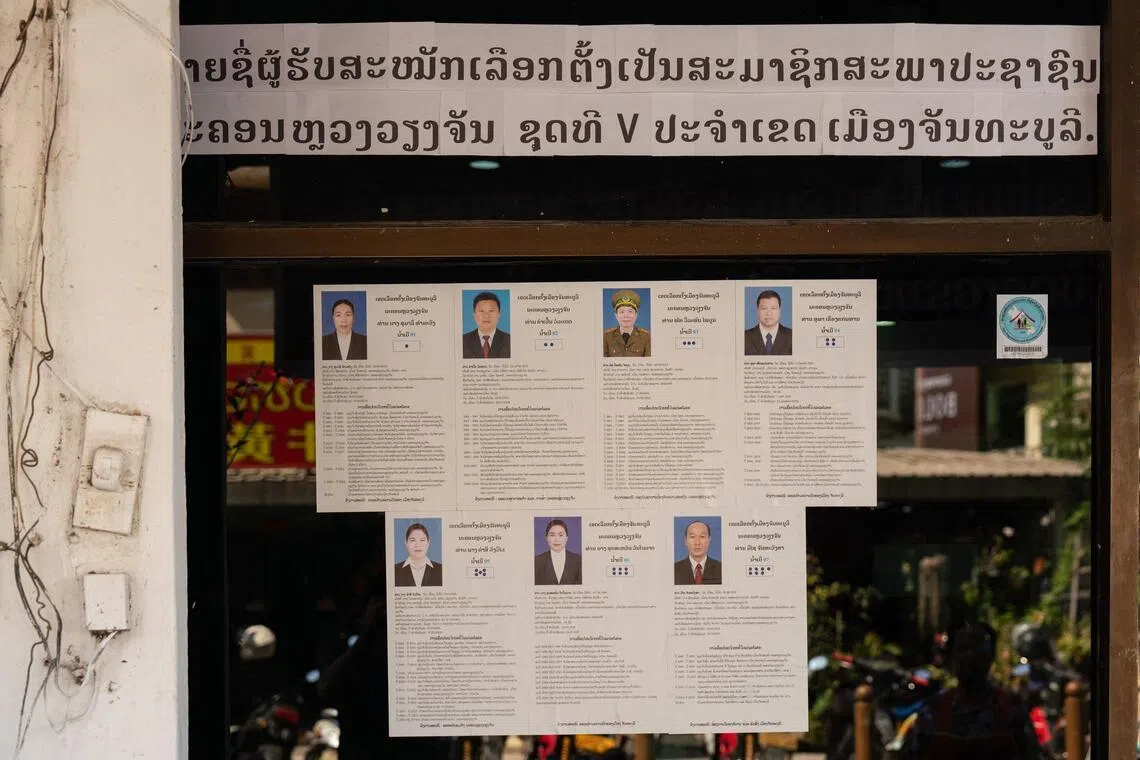

The Feb 22 election will see 243 candidates contest 175 seats after being pre-selected by the ruling communist party.

PHOTO: AFP

BANGKOK – When one of the few lawmakers willing to call out corruption in single-party Laos was left off the candidate list ahead of this weekend’s heavily managed election, a rare wave of dissent erupted.

Weeks after the candidates were publicised, outspoken MP Valy Vetsaphong announced she had removed herself from the ballot, ending her decade-long career in parliament – but some remain sceptical about her departure.

Her announcement came just days before Feb 22’s poll, in which all 243 candidates contesting 175 seats are pre-selected by the ruling communist party, making the exercise largely performative.

The South-east Asian nation has no opposition parties and no fully independent news outlets. The ruling Lao People’s Revolutionary Party has held power for more than 50 years.

Dissent is dangerous, protests are swiftly crushed and government critics are often jailed or disappear.

But after Ms Valy, one of only six non-communist party members allowed in the National Assembly, said she was quitting politics to focus on economic development work and allow herself “more personal time”, social media erupted.

Some users openly expressed support for her online, while others voiced discontent over her exit – revealing a rare crack in the state’s overarching control.

Comments referred to her as “number one in the hearts of the people” and warned that “those who speak for the people are often eliminated”.

“It’s sad to see this, as she was very vocal and really represented the Laos people,” said a 30-year-old development worker in the capital Vientiane.

Ms Valy, who serves on the board of Laos’ chamber of commerce, may have been allowed more space to speak out due to her business background, said the development worker, who requested anonymity for security reasons.

Despite the stiff restrictions in Laos, he pointed to signs of change, such as more online discussion about politics and younger candidates on the ballot compared to previous elections.

“It may look the same, but we do see some improvements, more openness from the government, and things are more relaxed compared to the past,” he said.

Laos state media this week also touted a shifting profile of candidates.

“Younger and middle-aged candidates make up the majority,” the Lao News Agency said, adding that the government was aiming to elect women to at least 30 per cent of seats.

But Ms Valy will not be one of them.

Speaking bluntly

The 57-year-old representative of Vientiane and medical clinic owner made her name with unusually blunt speeches in which she called on the state to step up anti-corruption efforts and enforce punishments for financial crimes.

Ms Valy once demanded corrupt officials be “punished and demoted as in other countries” rather than merely warned, and lobbied for a complete overhaul of the financial sector to address Laos’ currency crisis.

She also vocally opposed selling majority control of state-owned carrier Lao Airlines to China, criticised electricity price hikes and advocated for tourism police to better serve foreign visitors – all positions that resonated with Laotians frustrated by economic hardships and limited accountability.

In a lengthy Facebook post on Feb 16 explaining why she was not standing in the election, Ms Valy thanked party officials, saying she wanted to step back from politics and “give younger representatives the opportunity to step forward”.

“I have had the opportunity to be a voice for the people and to reflect their concerns to the relevant authorities,” the post reads.

“It is important to recognise that progress happens when leadership listens to the people through their representatives.”

Ms Valy declined an interview request from AFP.

‘The only hope’

Ms Emilie Palamy Pradichit, executive director of rights group Manushya Foundation, said it was unlikely Ms Valy “stepped down of her own accord”.

“We think she was put under pressure,” Ms Pradichit told AFP. “She’s not that old; she could have stayed on.”

But with a younger generation that is increasingly vocal on social media, Ms Pradichit said Ms Valy’s re-election “would have been problematic in the eyes of the one political party”.

“Her voice mattered a great deal, especially to young people,” Ms Pradichit added.

“Valy Vetsaphong really was the only hope.”

A 28-year-old Laotian living in Vientiane said many people had “expressed disappointment about not seeing her participate again”, which showed the “level of support she had built”.

About two weeks after the candidate list without Ms Valy’s name was released, prominent Laotian activist Joseph Akaravong publicly endorsed her anyway, sharing her CV to his nearly 700,000 Facebook followers.

Mr Akaravong, who fled Laos in 2018 and survived an assassination attempt in France in June, has long been critical of the government, and his page functions as a forum for debate about Laotian politics and society.

“She wasn’t selected,” he wrote of Ms Valy, “possibly because she had too much public support, which may have been seen as annoying.” AFP