Malaysia national service can be valuable experience, say past recruits ahead of proposed revival

Sign up now: Get insights on the biggest stories in Malaysia

Ms Chai Jia Yu was 18 when she was drafted to join Malaysia’s National Service Training Programme (PLKN) in 2006. Like many others in her cohort, she was uncertain about what to expect at the beginning of her three-month stint in the camp.

“At first, some people really did not like the feeling of living away from home, in groups of 10 to a room,” said the Johor-based digital marketer, who is now 35.

But looking back, she is grateful for the experience. In fact, she said many other trainees who reported to the camp crying also left in tears, but for very different reasons.

“After getting used to the environment and enjoying the experiences, they left the camp in tears again, this time because they could not bear to leave behind their friends,” Ms Chai said.

While Ms Chai has fond memories of her national service training, recent proposals to revive the programme for Malaysians have sparked a range of reactions, from disbelief to derision.

Older millennials in their early 30s were initially concerned about being drafted into the programme after Defence Minister Mohamad Hasan said in Parliament that potential recruits would include Malaysians as old as 35 years old.

They said their lifestyle would face more disruption than school-leavers should they be enlisted.

Many were also worried whether they could cope with the exercise regimens involved.

But their concerns were largely assuaged after the Defence Ministry clarified last Friday that only teenagers would be called up for in-camp training.

They can request for deferment if they have a valid reason, but the maximum age to serve as a trainee is 35, the ministry added.

Malaysia selected its first batch of 85,000 PLKN male and female trainees in 2003 using a ballot system.

The programme was paused in 2015 due to cost concerns, but was reintroduced in 2016 with a focus on work skills.

In 2018, the newly elected Pakatan Harapan administration abolished the programme

While many remain doubtful about the need to bring back a costly programme amid the current economic uncertainties, past enlistees like Ms Chai said the experience it offered was priceless, for it allowed young Malaysians to make friends across the racial divide.

“There were many people, especially Chinese independent school students, who had never interacted with other races at length during their school years,” she said.

But at the camp, all trainees were expected to go through physical training and character-building lessons together.

There were also cultural exchange components, with Malay trainees putting on silat shows and Indian trainees showing off their dances, she said.

“Team-building activities such as obstacle courses and competing with other groups at the camp required teamwork and pushed us to be united.”

Safety at the camps had previously been flagged as a concern, after more than 20 reported deaths have been tied to the programme over the years.

There were also some reports of sexual harassment and food poisoning.

But Mr Kee Jia Jun, who was enlisted to Pagoh, Johor in 2006, said cases of abuse and poor hygiene might have been isolated ones.

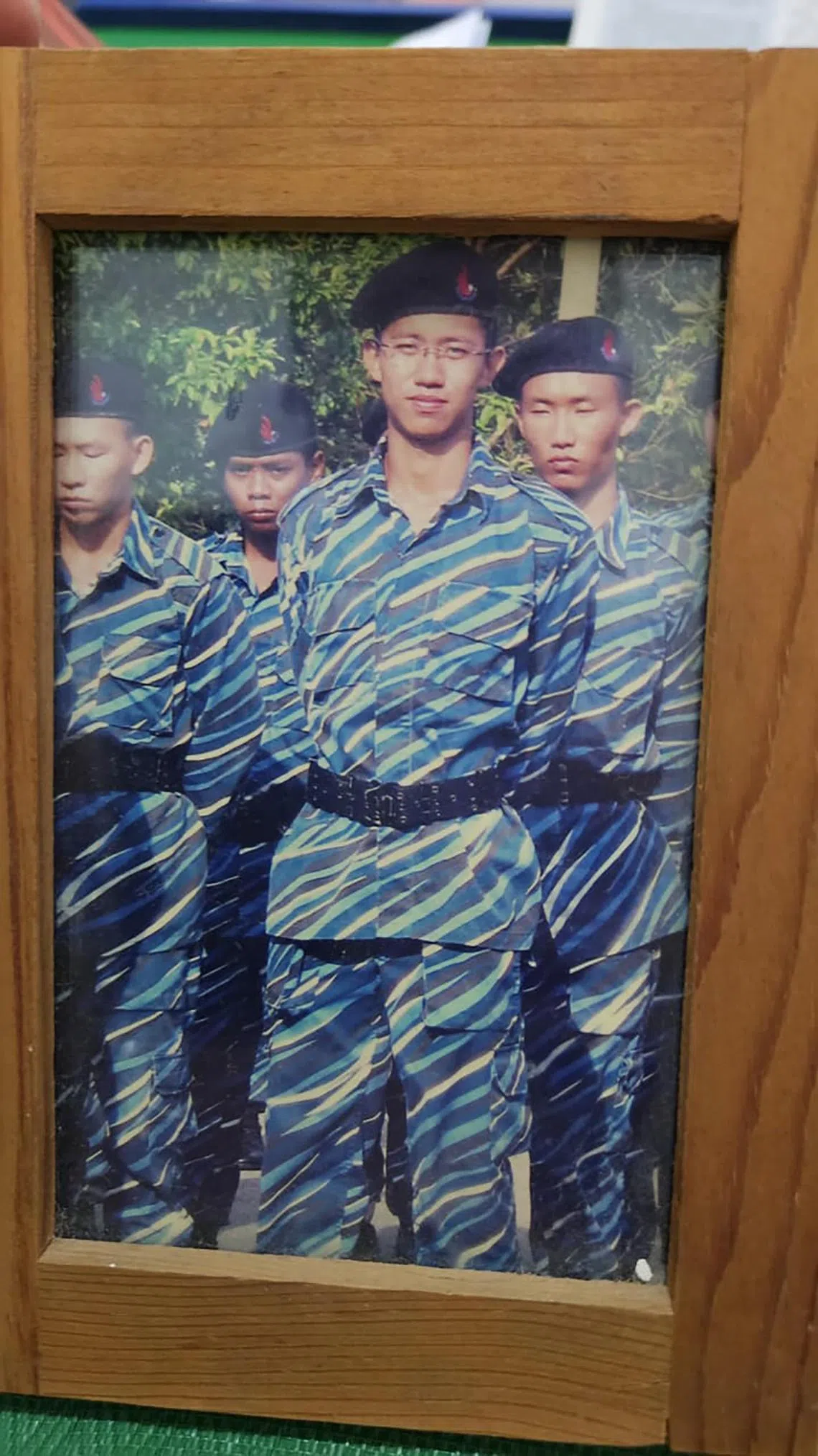

Mr Kee Jia Jun wearing a trainee uniform during his national service stint at 18 years old.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF KEE JIA JUN

“Some of the coaches would punish us to do push-ups or roll on tarmac roads, which could be painful,” he said.

“Overnight guard duty could be tough, but training was reasonable, it never crossed the line.”

Now a businessman, the 35-year-old added that those at his camp were well-fed with up to six meals a day. He also met his wife who hailed from neighbouring state Melaka at the camp.

Having a chance to learn to be independent was another valuable takeaway for him.

“It was a good opportunity to build self-reliance and not depend so much on your family,” he said.

A batch of Malaysian national service trainees at Mr Kee Jia Jun’s camp in Pagoh, Johor.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF KEE JIA JUN

Mr John Chua, who was assigned to a camp in Balik Pulau, Penang, in 2008 said his experience helped prepare him for adulthood and hone his discipline.

While he appreciated the opportunity to meet trainees from all walks of life, he said the three-month stint would not be enough for deep friendships to flourish.

“Over a short period covering a few months, I feel achieving cross-racial integration is still limited,” he said.

The new PLKN 3.0 is slated to be held at 13 existing training centres, a departure from its previous runs when multiple new sites including activity grounds and living quarters were built to host trainees.

A working proposal will be sent to the National Security Council in 2024.

If approved, the training will be cut from three months to 45 days, partly to reduce the annual budget from RM500 million to around RM100 million.