Blog

Myanmar-Thailand road cuts through last wilderness

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

Across the open door of the immigration office, a black dog sleeps, his ears twitching. It is a slow day at the border, under the tropical afternoon sun.

The incessant whine of cicadas off the bumpy red dirt road at my back, snaking through the hills from the west, will soon give way to the roar of traffic and a smooth Thai highway to Bangkok in the east.

But first the Myanmar immigration officers spring to life, taking off the plastic covers of their computer monitors when I appear through the door, stepping around the dog. It is not often that a foreigner comes through here. But the development of Dawei, from where I have just come, could in a few years change all that.

In the colonial period, Dawei was called Tavoy, and the state Tenasserim; today the state is called Tanintharyi.

Dawei was so isolated then, that the British exiled King Mindon's chief queen - the Lady of the White Elephant and mother-in-law of Myanmar's last King Thibaw - to Tavoy. The yellowed former university building where she lived out her days in exile is today an educational institute filled with the laughter of young women.

PHOTO: WORLD WIDE FUND FOR NATURE

Today, Dawei is still not on the national electricity grid. It is connected with Yangon by air, with a few flights a day; the alternative is almost an entire day's road trip. Dawei is 678km from Yangon.

But it is only 350km from Bangkok. Therein lies its appeal, especially to Thailand. The juggernaut of the long-delayed Dawei Special Economic Zone project (SEZ) - first proposed in 2008 and only this year in a fresh agreement, given a new lease on life - has begun to roll.

The project will be years in the making, not least because the attitude of a range of local residents interviewed in Dawei ranged from neutral to negative, and Dawei has strong civil society advocacy groups wary of big corporate interests and demanding transparency and impact assessments.

But one of the first aspects to be developed is the road I had just travelled on.

I had started in the lush green coastal plains of Dawei, fringed by the Andaman Sea on one side and rising hills on the other, driving through swamps and rice padis and alongside lazy swollen streams.

The red dirt road snaked into the hills, at times potholed, at times narrowing to small bridges across mountain streams. This is the road to the Thai border at Phu Nam Ron, where after you cross Myanmar Immigration you drive through a stretch of no man's land and then reach Thailand Immigration.

Its 138km are set to be developed into a two-lane highway to serve the Dawei SEZ, reducing travelling time to Bangkok from the current seven hours, to closer to four hours. This section will be part of the so-called Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Southern Corridor, offering a land connection for heavy trucks from Dawei in the west, through Thailand and Cambodia, to the coast of Vietnam in the east.

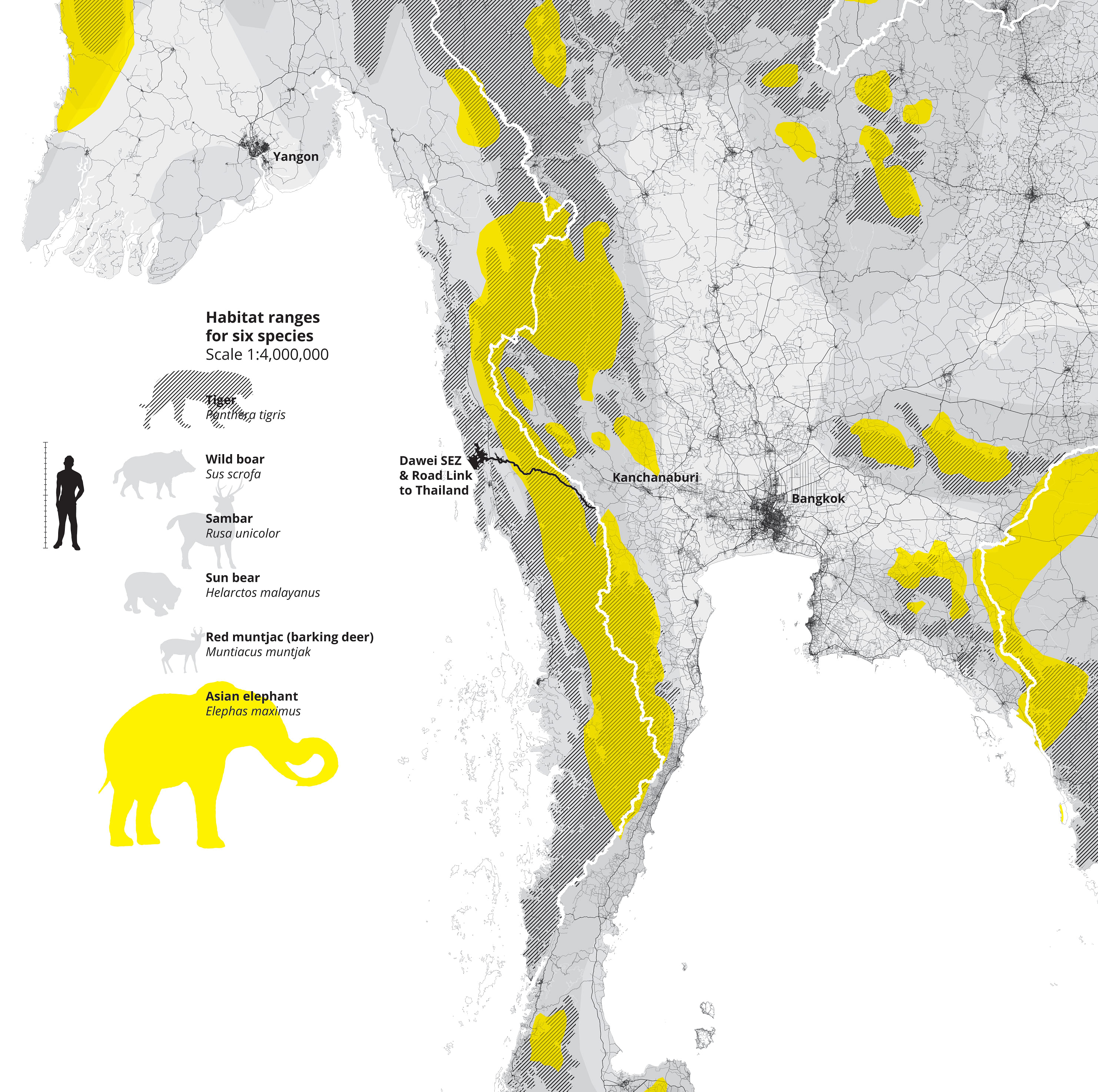

It also bisects what is almost certainly mainland South-east Asia's last great relatively intact, biodiversity-rich wilderness - one that is in parts contiguous with Thailand's chain of national parks called the Western Forest Complex - and one that could be lost very rapidly if measures to limit environmental risk are not taken ahead of time.

Roads alter landscapes. They can alter water flow and trigger erosion and landslides, especially in unstable mountainous terrain. They block all manner of wildlife movement.

And they also open up previously relatively untouched wilderness to commercial exploitation - which multiplies the damage many times over.

There is significant deforestation - mostly for rubber plantation - along the road already. In places, entire hilltops are bald. A researcher who had surveyed some areas, told me he once walked off the road for three hours through open land before finally seeing the forest "almost like a mirage" on the horizon, so great has been the clearing.

The conversion to plantations goes well beyond the road. All Myanmar's oil palm concessions are located in Tanintharyi, where nearly 28,000ha of rainforests had been cleared or burned in 2010 and 2011 to make space for the crop, a report by the independent organisation Forest Trends said.

According to the March report, Myanmar's oil palm concessions are owned by about 40 Myanmar businesses with strong ties to political and military leaders, the Ministry of Industry and the Union of Myanmar Economic Holdings - the military's business and investment arm.

Myanmar is in danger of losing what a paper in the journal Conservation Biology calls a "rare survival in a biodiverse but otherwise heavily degraded region".

"Their lowland topography, one of the attributes that makes them so valuable for biodiversity, also renders them extremely vulnerable to logging, land speculation, hunting, and the expansion of agriculture and agro-industrial plantations. This vulnerability is exacerbated by their long border with mainly deforested and resource-hungry Thailand," the paper says.

Tanintharyi is at the meeting point of the Indochinese region and the Malaysian Peninsula and has an astonishing level of biodiversity, including the near-vanished Gurney's Pitta, Malayan tapirs, tigers and potentially, Sumatran rhino.

The development of the road presents multiple challenges. Some of the area it passes through is under the control of the government, and some is controlled by a section of the Karen National Union (KNU).

The KNU is in a ceasefire with the government, and may sign a more inclusive ceasefire soon which would, in effect, turn it into a legal group and enable many more international agencies - including the United Nations and of course, corporations - to engage in the area.

A clutch of international non-government organisations from the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) to the Wildlife Conservation Society and Flora and Fauna International are busy working to map the biodiversity of the area, identify critical parts that need protection, and train local people, including the KNU, in forest and wildlife protection.

A WWF report released in June this year, titled "A Better Road to Dawei", made a series of recommendations on planning, design and mitigation measures such as wildlife crossings and stabilising slopes in key areas.

An e-mailed query to Italian-Thai Development (ITD), which is developing the road and the SEZ, asking if the company was considering any of the recommendations, had not been replied to by the time of publication.

Analysts and environmental experts familiar with the issues say while mitigation measures would cost money, ITD could both avoid environmental risks that would be expensive down the road, as well as avoid reputational risk and be seen as model, environmentally sensitive road builders, if they built in measures from the outset to limit the effect of the road on the environment.

Ms Hanna Helsingen, an environmental policy expert with WWF based in Yangon, in an interview said locals had told researchers they sometimes saw sun bears strolling on the road. And on a recent field trip, she saw a flock of Great Hornbills fly high above the road at sunset, filling the sky with the sounds of the powerful beat of their big wings.

"There is a lot that needs protection," she said. "And it is not too late at all."

nirmal@sph.com.sg