News analysis

Megawati makes power gamble with party leaders’ pullback from Indonesian President Prabowo’s retreat

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

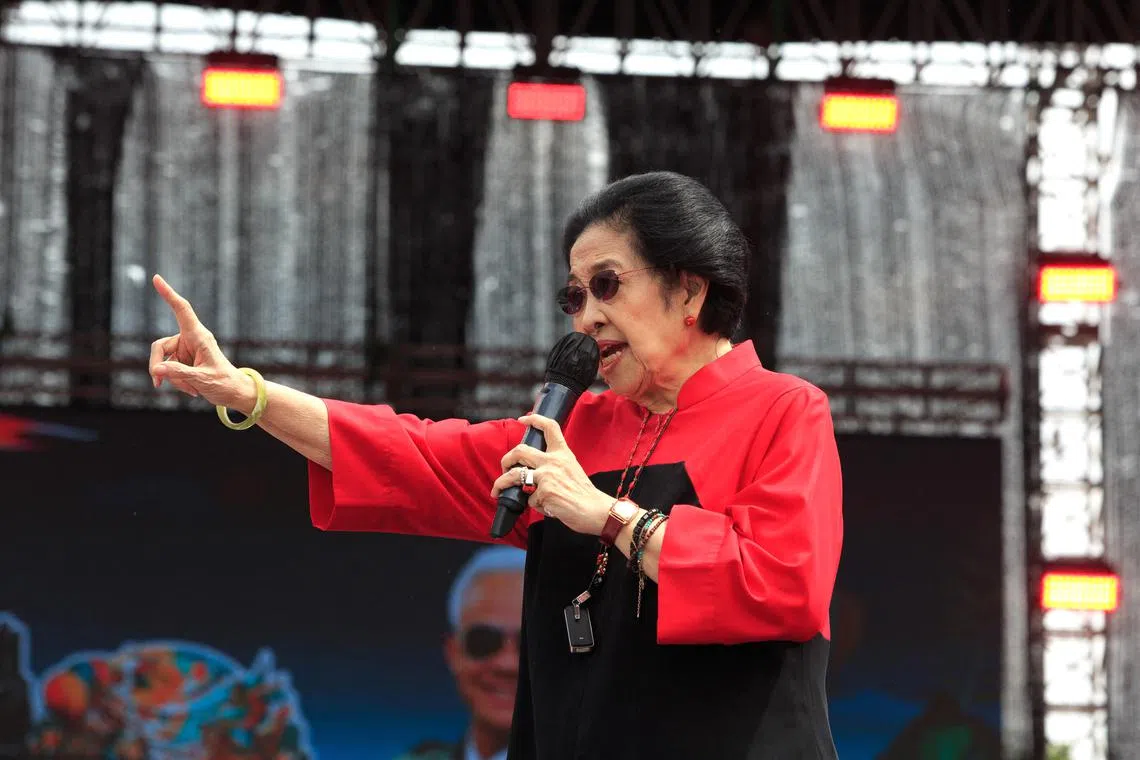

Ms Megawati Soekarnoputri, chairwoman of Indonesia’s largest political party, at an election campaign rally for the party’s candidates in Central Java in February 2024. PDI-P emerged the top party in the 2024 legislative election.

PHOTO: AFP

JAKARTA – Hours after her trusted aide’s arrest

The newly inaugurated representatives from the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDI-P) were told to delay their travel to the retreat, and, for those on their way, to stop and wait for further instructions from the party chair.

The party was “monitoring the evolving dynamics of national politics following the legal criminalisation of PDI-P secretary-general Hasto Kristiyanto” by the Indonesian Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK), they were told.

This saw many of them gathered in a cafe in the Central Java city of Magelang, instead of at the military academy where the Feb 21 to 28 “boot camp”

However, most eventually attended the event, where senior officials briefed leaders on the President’s vision.

The deadlock was broken on the fourth day by PDI-P loyalist Pramono Anung, the new Jakarta governor and former Cabinet secretary, who “communicated and coordinated” talks between the central government and the party leadership, confirmed PDI-P spokesman Ahmad Basarah in a press conference on Feb 25.

Mr Basarah stressed that Ms Megawati “never disallowed” their attendance at the retreat, and their eventual participation was with her knowledge.

He added: “PDI-P’s position remains that we have no issues with President Prabowo.”

Of Indonesia’s 503 regents, mayors and governors, 97 – nearly one-fifth – are from PDI-P, which also emerged the top party in the 2024 legislative election, securing 110 of the 580 parliamentary seats.

Analysts say Ms Megawati’s directive points to an ongoing power struggle

Mr Arif Susanto, a political analyst at Jakarta-based Exposit Strategic, told The Straits Times that he believed Ms Megawati’s instructions were a knee-jerk reaction to the arrest of her close ally Mr Hasto.

In December 2024, the KPK named Mr Hasto a suspect

His arrest in February prompted the party to question why a six-year-old incident was being dragged out now, suggesting that this was an attempt to weaken the party.

“Losing Hasto meant something personally for Megawati. But her reaction was emotional, hasty and less than strategic,” said Mr Arif.

The Indonesian anti-corruption agency named Hasto Kristiyanto as a graft suspect in December 2024.

ST PHOTO: WAHYUDI SOERIAATMADJA

The November 2024 regional election saw troubling allegations of central government bias

Political analyst Djayadi Hanan from the Indonesian Survey Institute said that, if it was not an emotional reaction, Ms Megawati’s directive could have been part of her strategy to demonstrate that she can take a “firmer stance” and try to put Mr Prabowo in a “defensive position”.

“Megawati knows that the retreat in Magelang is a priority for Mr Prabowo. He wants to show everyone that he is in command. If many subnational leaders from PDI-P (did not attend), that could be a dent to Prabowo’s political legitimacy,” he said.

PDI-P, the only party in Indonesia’s Parliament that is not in Mr Prabowo’s coalition, has long been expected to take an opposition role after a public feud with Mr Widodo

The relationship between Ms Megawati and Mr Prabowo, her running mate in the 2009 presidential election that she eventually lost, has been marked by ups and downs.

Since the 2024 elections, a meeting between the two politicians has been anticipated, with observers suggesting it could pave the way for PDI-P, now the de facto opposition, to join the government.

Though they have yet to meet, Ms Megawati has repeatedly emphasised her good relationship with Mr Prabowo. On Jan 23, he sent her a bouquet of flowers for her 78th birthday, despite missing the celebration because of a state visit to India.

But Mr Hasto’s arrest has left the PDI-P chairwoman in a bind.

In January, Ms Megawati said in an address at the party’s 52nd anniversary celebrations: “People think (Mr Prabowo) and I are enemies. That’s not the case. But I did tell him, since we are both chairs of our own parties, how would he feel if his party members were treated unjustly? I’m sure he would feel the same way.”

PDI-P is expected to announce its official stance towards the Prabowo administration during its upcoming congress in April, which will also include a race for the party chairmanship.

Analysts believe it is more likely that Ms Megawati and her party will stay on the opposition bench, which is some party members’ preference. Another reason is the continued influence that her political rival, Mr Widodo – better known as Jokowi – has in the Prabowo administration, in which his son Gibran Rakabuming Raka is Vice-President.

PDI-P also enjoys support from the public, particularly civil society, who want an influential ally in government to champion their issues.

“But, at the same time, Megawati has other party members saying it is better for PDI-P to be part of the government, saying, ‘If we want to fight against Jokowi, it’s better to fight him inside the government. If we’re not part of it, Jokowi will become much, much more influential,’” Dr Djayadi said.

Dr Djayadi noted that within the Prabowo administration, there are differing views on whether PDI-P should join the government too, adding: “It seems that they are in an ongoing, indirect negotiation process. I don’t think the question of whether Megawati will be in opposition will be resolved soon.”

Mr Arif stated that Ms Megawati will “remain in opposition without being confrontational” and will leverage Mr Pramono, a neutral figure respected by her political rivals, to negotiate a “win-win solution” if any future issues arise, safeguarding her political standing without provoking her adversaries.

“On the ground, the PDI-P still holds significant influence. However, the highly personalised nature of Indonesian politics means Jokowi’s power remains strong. The real challenge is she faces limited funding, with oligarchs now aligned with both Jokowi and Prabowo,” he said.

Dr Djayadi highlighted that while Ms Megawati highly valued Mr Hasto, defending him could prove costly, as the KPK, the Supreme Court, and the police are all under Mr Prabowo’s influence.

“Ultimately, the legal process is controlled by Prabowo’s government. Putting everything on the table to defend Hasto against Jokowi could be an unwise strategy,” he said.

Analysts say Mr Prabowo and Mr Widodo are close and need each other politically for now, but the dynamics could shift if Mr Widodo poses a threat to the current Indonesian leader.

Mr Arif said: “The situation could change in two years. By then, the government will have completed half of its term. If Prabowo succeeds as a leader (and gains public approval), his power will be consolidated; if he fails, Jokowi’s influence will grow even stronger.”

He added: “For Jokowi, he has a lot at stake and must maintain his political influence. He has put everything on the line, politically and economically, and his family is also deeply involved in politics. The stakes are too high; he simply cannot fail.”

Arlina Arshad is The Straits Times’ Indonesia bureau chief. She is a Singaporean who has been living and working in Indonesia as a journalist for more than 15 years.