Malaysian Mandopop fans turn to Malay in resistance against China’s ‘yellow cows’

Sign up now: Get insights on the biggest stories in Malaysia

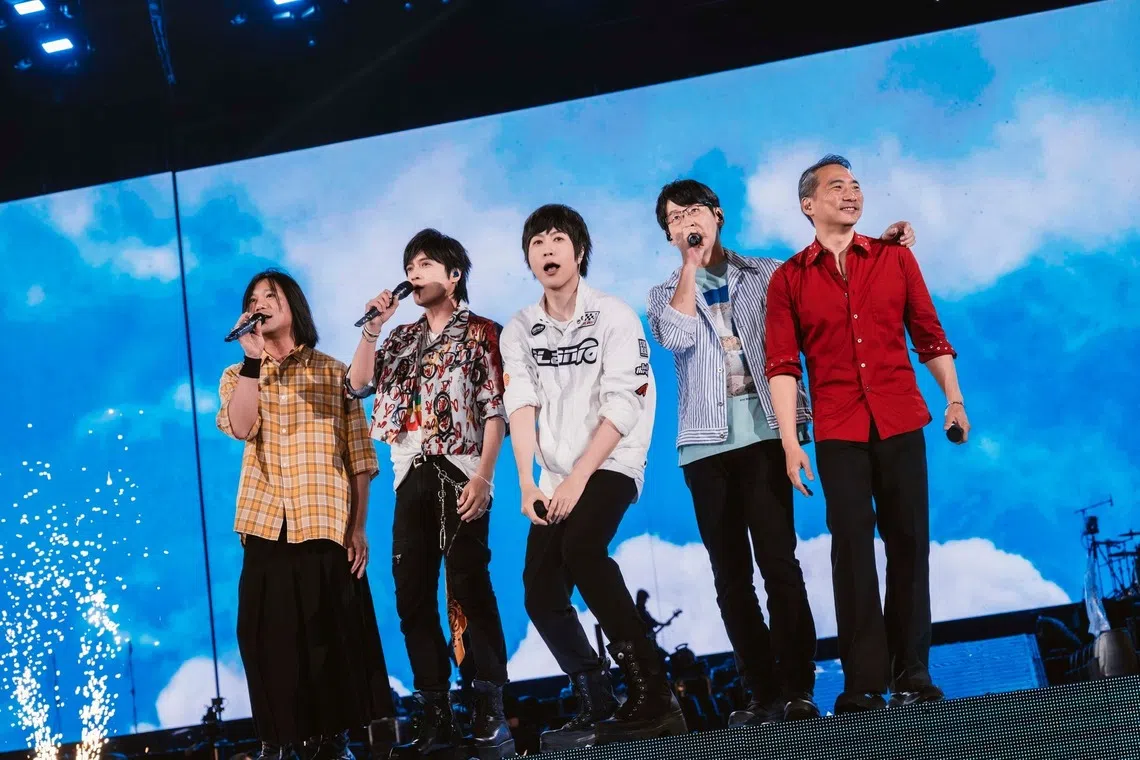

Malaysian fans say they find it hard to get tickets to Taiwanese rock band Mayday's 2026 concert in Kuala Lumpur.

PHOTO: B'IN MUSIC/FACEBOOK

- Malaysian Chinese concertgoers use Malay to criticise Chinese scalpers pricing them out of local shows, highlighting tensions over ticket access.

- Scalpers resell tickets at inflated prices, such as RM28,000 for G-Dragon's concert, leading to outrage and claims of non-Malaysian dominance.

- Real-name ticketing and ID checks, like in Korea, are suggested to prioritise locals and combat scalping, ensuring fair access.

AI generated

KUALA LUMPUR – Scroll down to the comments section of the Facebook page of concert promoter B’in Music, which is bringing Taiwanese band Mayday to Kuala Lumpur in January 2026, and you may find something remarkable: a sea of Malay words amid the usual Chinese comments.

One of the most frequently mentioned phrases was “lembu kuning”, which means “yellow cow” in Malay. The term riffs on the Chinese slang for concert scalpers, which originated in 20th-century Shanghai, where labourers mobbed ticket counters like frenzied oxen to hoard tickets and resell them at a mark-up.

Here, the Malay comments came from ethnic Chinese concertgoers from Malaysia, who weaponised the local language to express frustration that they had been priced out of their home shows by scalpers from China, who snapped up tickets via bots and proxies.

“Yes, we queued up and waited but got tickets far away at the back. Yellow cows are selling tickets for front seats, in the middle with better views,” user Ham ManChin wrote in Malay in a Dec 3 Facebook post.

“Too many yellow cows selling tickets. What can we do?” added another user, HappySong Jenny, also in Malay.

With Malay comments flooding the post, another user, Jannifer Hsiaomayi, joked by asking if the rock band actually sings in Malay instead of Mandarin.

Even the local concert promoter got in on the act, telling fans to “try again today” in Malay.

Ethnic Chinese make up just over 23 per cent of Malaysia’s population. The Malay language is a compulsory subject in both national and vernacular schools, although it may be taught as a second language in schools that teach in Mandarin.

When K-pop star G-Dragon performed in July 2025, Malaysian fans were fuming that over 90 per cent of attendees were non-Malaysians – mostly Chinese nationals – as reported by local newspaper China Press.

Locals were also outraged when VVIP tickets that cost RM1,339 (S$420) were scalped online for up to RM28,000, and reportedly snapped up by affluent Chinese nationals. The lack of Malay wording in signage and announcements was also criticised, causing the organiser to vow to make improvements in the future.

Frequent concertgoer Fish Lee, 30, said the influx of Chinese fans made her feel like she was not at a show in her own country. She cited the song-request session at Taiwanese Mandopop star Jay Chou’s concert in Kuala Lumpur in October 2024 as an example.

“Chinese fans made four out of five successful requests. The seats closer to the stage were locked by scalpers, who then sold the tickets to them. Many fans complained: ‘Is the show in Malaysia or China?’” the logistics executive told The Straits Times.

Malaysia has been attempting to position itself as an emerging destination for international performances. It is expected to hold 450 concerts

Malay language as demarcation

The anger towards Chinese fans feeding the scalping economy is just another example of Chinese Malaysians’ concerns about fierce competition posed by Chinese nationals at a personal level, political scientist Wong Chin Huat told ST.

“Mandarin literacy enables Chinese Malaysians to understand China, but it doesn’t erase the distinctions between them and China nationals. Part of Chinese Malaysians’ identity is their ability to speak Malay.

“When there is a need to distinguish themselves from Chinese nationals, speaking Malay becomes a natural means,” the Sunway University professor told ST.

An unintended consequence of Chinese scalping activity, Prof Wong suggested, is the uniting of Malaysians of different ethnic backgrounds as they use Malay, noting that “group competition against foreigners is more effective than official policy in promoting national identity and unity”.

This played out in another arena in September 2025, when Malaysia’s mixed-doubles aces Chen Tang Jie and Toh Ee Wei were heard discussing tactics in Malay when facing China’s World No. 1 pair Feng Yan Zhe and Huang Dong Ping in the semi-finals of the China Masters.

Ironically, “neijuan”, a term that originated in China to describe pointless competition

Since a visa-free arrangement with China began in December 2023, Malaysian businesses have complained of unfair or excessive competition from Chinese nationals in sectors ranging from manufacturing to service.

Concert fans feeling a similar exhausting competition for tickets hope that event organisers will implement a real-name ticketing system and ID checks similar to those used in South Korea.

Such ID checks compare the name on a ticket with a valid photo ID, to ensure the ticket holder is the actual purchaser, and help combat scalping.

Long-time K-pop fan Cheong Yi Fang, 23, said the ID check is necessary because Malaysian taxpayers’ money contributed to the construction of concert venue infrastructure, and therefore locals should not be left out.

“Real-name ticketing, priority access for locals when ticketing opens, or any form of action to prioritise locals would be a fair form of return,” Ms Cheong said.

Sign up for our weekly

Asian Insider Malaysia Edition

newsletter to make sense of the big stories in Malaysia.