Indonesia’s seawall project set to expand – good for some, but gloomy for others

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

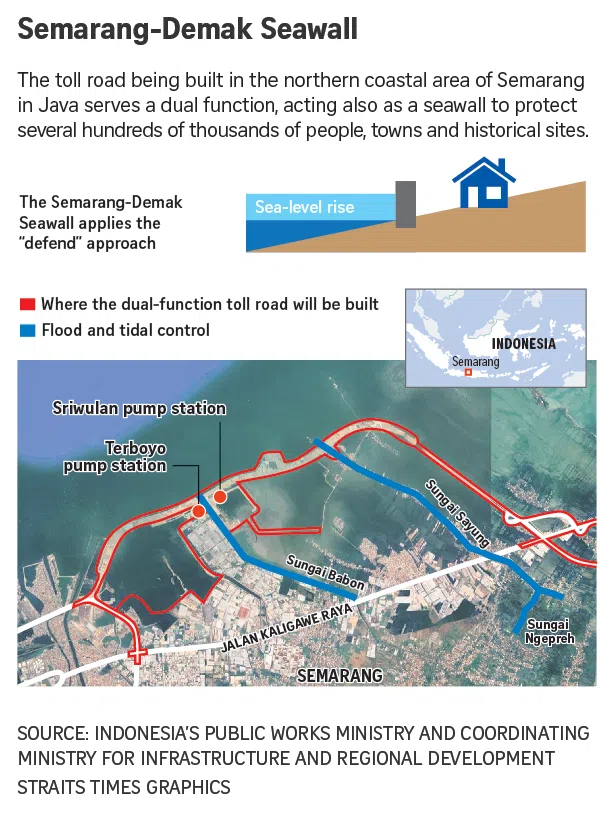

The Semarang-Demak seawall serves a dual function as a toll road that extends from the mainland, crosses the sea, and connects back to the land.

ST PHOTO: WAHYUDI SOERIAATMADJA

- Indonesia is building seawalls along Java's coast to combat rising sea levels, with the Semarang-Demak section doubling as a toll road.

- The seawall project has drawn mixed reactions, with some residents welcoming it, while fishermen report reduced catches due to the construction.

- The government plans customised sea defence structures, prioritising populated areas like Jakarta and Semarang, avoiding a 'one-size-fits-all' approach.

AI generated

SEMARANG/DEMAK, Central Java province – Ms Pangestuti, a mother of one, has become used to cooking in her kitchen while standing knee-deep in seawater. It has been like this for almost 10 years.

“We trust the government will help us. I pray things will return to normal some day,” said the 41-year-old housewife, who like many Indonesians goes by one name. She lives in the coastal village of Bedono, which has been affected by rising sea levels for years.

But relief is on the horizon with the 6.7km Semarang-Demak Seawall that also serves as a toll road. It looked to be half-completed when The Straits Times visited on Oct 2.

As Indonesia accelerates efforts to protect the northern coastal areas of Java – its most populous island, home to more than half of Indonesia’s 284 million population, and the hub for over 55 per cent of the national economy – by constructing seawalls, early sections of the infrastructure have already drawn mixed reactions.

Small-boat fishermen have voiced unhappiness, complaining of reduced catches, while other residents, especially those whose front and back yards are now permanently inundated with seawater, welcome the project as long overdue. Semarang is among the Indonesian cities grappling with severe land subsidence after decades of excessive groundwater extraction.

Work on the Semarang-Demak Seawall along the coast of Central Java, which started in 2023 under the Jokowi administration, is set to be completed in 2026. The smaller seawall will be part of a massive structure stretching hundreds of kilometres along the nation’s main Java island to prevent flooding and coastal erosion.

Construction of a giant seawall is expected to cost US$80 billion (S$104 billion) and take about 20 years to build, President Prabowo Subianto said in a speech to investors at the International Conference on Infrastructure in Jakarta on June 12. It will span at least 500km from the island’s westernmost city of Banten to Gresik regency in East Java.

The government will not apply a “one-size-fits-all” approach by building a uniform seawall along the Java coast from end to end, Mr Rachmat Kaimuddin, Deputy Coordinating Minister for Infrastructure and Regional Development, told The Straits Times on Oct 4 in Jakarta.

“We are not building one resembling the Great Wall of China that stretches continuously for hundreds of kilometres from Banten to Gresik,” he said, adding that different regions will have their own customised structures.

Mr Rachmat told ST that the areas to be prioritised are those with a large population or with high economic or historic value, with Jakarta and Semarang topping the list, followed by coastal cities Cirebon (West Java province) and Pekalongan (Central Java province).

In August, Mr Prabowo set up an agency called the North Java Coast Sea Wall Management Authority to oversee the giant seawall project, which has been part of Indonesia’s national blueprint since 1995 yet has never been developed.

Plans for a smaller seawall along the coast of Jakarta have also been discussed for over a decade, with the capital being one of the fastest-sinking cities in the world. The Jakarta segment of the seawall alone would take about eight years to complete, the President said.

Mr Rachmat said the government will put together previous reports on the seawall construction plan and come up with one main masterplan.

“We have done a lot of discussions and there were a lot of studies conducted. Now, President Prabowo wants to execute it,” he added.

In Semarang-Demak, the approach is to set up fortress-like barriers, Mr Rachmat said. But in other areas that are not as densely populated, the government will adopt a retreat strategy, involving moving the population farther inland and planting mangroves to serve as a natural defence against the rising tide. Yet another way might be to rely on a system of hilly dikes to keep certain areas dry, he added.

A satellite image of the Semarang-Demak Seawall.

PHOTO: SCREENGRAB FROM GOOGLE MAPS

Mr Dedi Kusuma Wijaya, managing director of Karsa City Lab, a Jakarta-based think-tank that advises on urbanisation and climate change, hailed the customised approach on the matter.

“That’s the proper approach. Oftentimes, we force ourselves to aim for a gigantic project and we never start realising it,” Mr Dedi told ST.

While the seawall is intended to protect cities from floods and land subsidence, some experts have flagged concerns about the potential economic harm for fishermen and local communities who rely on the sea, as well as the disruption to the marine ecosystem.

In Bedono village in Demak, the seawall project has garnered a mixed reception.

Ms Pangestuti, a resident of Demak, is thankful for the seawall that the government is building and believes some day that life will return to normal.

ST PHOTO: WAHYUDI SOERIAATMADJA

Some villagers are looking forward to seeing their living conditions improve.

“We look forward to seeing the seawall completed. Water rose about a decade ago and our house has been permanently flooded. Some neighbours who could afford it have moved elsewhere. We cannot afford to,” said Mrs Fauli Munawar.

The 60-year-old, who lives with her son, daughter-in-law and a 12-year-old granddaughter, used to run a shoe store with her late husband but now relies on her son, who works as a lorry driver and is the family’s sole breadwinner.

But others say the construction of the seawall has had an adverse impact on their livelihoods.

Villager Sutrisno Nurman, 58, complained that the partially completed seawall has affected his milkfish farm as it blocks seawater from entering his farm’s pond, which is highly reliant on brackish water.

“Not only did the fish grow slowly, but their weight also did not reach the maximum. Buyers have complained that my fish tastes muddy,” Mr Sutrisno told ST, adding that such problems started to emerge in June.

Mr Sutrisno Nurman pointing to the seawall that he blames for affecting his milkfish farm, which requires brackish water.

ST PHOTO: WAHYUDI SOERIAATMADJA

When asked about this, Karsa City Lab’s Mr Dedi warned: “No one should feel overlooked... The government should find a creative way to make sure everyone’s interests are protected.”

He pointed to a 2019 case in north Jakarta involving the relocation of spinach farmers after their land was acquired by the government for a stadium. The municipal government helped the farmers make the shift to hydroponic farming – a method of growing plants without soil by using water-based mineral nutrient solutions.

In the meantime, some Bedono villagers continue to grapple with declining income.

Traditional fisherman Abdul Latif, 31, a father of a pre-schooler, said he has lost three-quarters of his income because fish is no longer as easy to find. He said: “Last time, it wasn’t hard to get fish, crab and mussels, and pocket 300,000 rupiah (S$23) a day. It’s no more like that now.”

Fisherman Abdul Latif has caught fewer fish, crab and mussels since the construction of a nearby seawall.

ST PHOTO: WAHYUDI SOERIAATMADJA