Field Notes from Pahang

In Malaysia’s ‘jungle railway’, a colonial-era train signalling ritual still survives

Sign up now: Get insights on the biggest stories in Malaysia

Kuala Krau station master Mohd Akmal Jamal (left), 31, handing a key token to the driver of an incoming train.

ST PHOTO: BRIAN TEO

- KTM's eastern railway uses a century-old "cota" signalling system with token exchange for safety on its single-track "Jungle Railway" since 1885.

- Station masters exchange physical tokens with train captains, ensuring only one train occupies a track section as a manual safety measure.

- While KTM modernises, the "cota" system remains relevant for safety, although railway enthusiasts fear it may be replaced.

AI generated

KUALA KRAU, Pahang – At a rural railway stop in Kuala Krau, Pahang, station master Mohd Akmal Jamal stands at the platform’s edge holding a weathered leather pouch with a horseshoe-shaped handle.

Midway down the platform, his assistant raises his elbow as if to throw a punch. As the train rolls in, the driver positions himself at the cockpit door and hangs a similar pouch around the assistant’s raised arm.

The driver then raises his own elbow and receives Mr Akmal’s pouch as the train continues moving.

Rarely seen any more, this century-old train signalling procedure is still practised in Malaysia’s eastern railway, even though operator Keretapi Tanah Melayu (KTM) has phased out traditional locomotives for diesel engines.

KTM modernised its fleet of traditional locomotives with diesel-powered trains in 2021.

Older locomotives are still in use today on the route solely for the daily “sleeper” overnight service from Tumpat in Kelantan to Johor Bahru, and for seasonal trips during festive holidays.

The railway company’s chief operating officer Afzar Zakariya said the route – which runs from Gemas in Negeri Sembilan to Tumpat in Kelantan – is the only one in Malaysia where this signalling system is still in use.

It is a safety mechanism to ensure that only one train is allowed to proceed from one station to another on the single-track line.

Called “cota” in Malay, it is a relic of the colonial-era Federated Malay States Railways, used since 1885.

The route spanning 526km on the eastern side of the peninsula is also known as Malaysia’s “Jungle Railway” since it passes through dense jungle and districts along the Taman Negara national park.

It is a single-track railway where only one train can pass in either direction at a time.

For railway enthusiasts, especially those from Singapore, the “railway token exchange”, as it is known, evokes memories of Singapore’s Tanjong Pagar railway station before it ceased operations in July 2011.

The token is exchanged between train drivers or crew and signifies clearance to proceed, based on security and traffic conditions.

ST PHOTO: BRIAN TEO

So what is in the pouch?

According to KTM, the signalling system permits only one train on the single-track line at a time.

The “key” is a token in a leather pouch passed between station masters and train captains. Each track segment has a unique token that is inserted into a box to signal the train’s arrival or departure.

At the Kuala Krau stop, Mr Akmal showed two red token boxes in his office, used for trains travelling to and from the station. Attached to them is an old telephone, which is still in use.

The cast-iron token boxes bear the label Tyer & Co, an old British company that produced railway instruments since the 1870s. Known as the Tyer No. 9 signal box, it is connected to other stations on the line via cables.

Two red token boxes from the 19th century are still employed in the Kuala Krau station.

ST PHOTO: BRIAN TEO

Mr Akmal explained that when a token is taken out of the box and given to the train driver, it will signal to the next station that a train is approaching.

“This method was widely used in train networks during the British era in the 19th century as a safety measure on single-tracked railways which are reliant on human communication and manual procedures,” he told The Straits Times.

But why the elaborate routine involving the elbows? Mr Akmal said that in the past, trains were longer, sometimes even exceeding the length of the train platform.

“This meant that station masters needed to walk quite a distance, even outside the station to fetch the token,” he explained.

For example, in the past in Tanjong Pagar, station masters even had to cycle just to fetch the tokens from the train cockpit.

Mr Akmal added that station masters could risk passenger safety if they left their posts. This is especially so in the eastern route, where sometimes locals could be seen by ST crossing or walking along the train tracks.

The elbow grab manoeuvre, Mr Akmal explained, allows station masters to pass the token to train captains without them moving out of their positions.

A close-up of the Tyer No 9 signal token box at Kuala Krau railway station.

ST PHOTO: BRIAN TEO

Is there future for the ‘cota’ system?

Railway enthusiast Zac Cheong, 47, told ST during a KTM media trip in January that the token system retains KTM’s old charm.

But he was worried that it may eventually lose its place to modern signalling systems. “It’s nice they still have it here, but if the tracks are due for an upgrade, there could be a chance it may be replaced as well,” he said, pointing to new electric railroad switches at the Kuala Krau stop in Pahang.

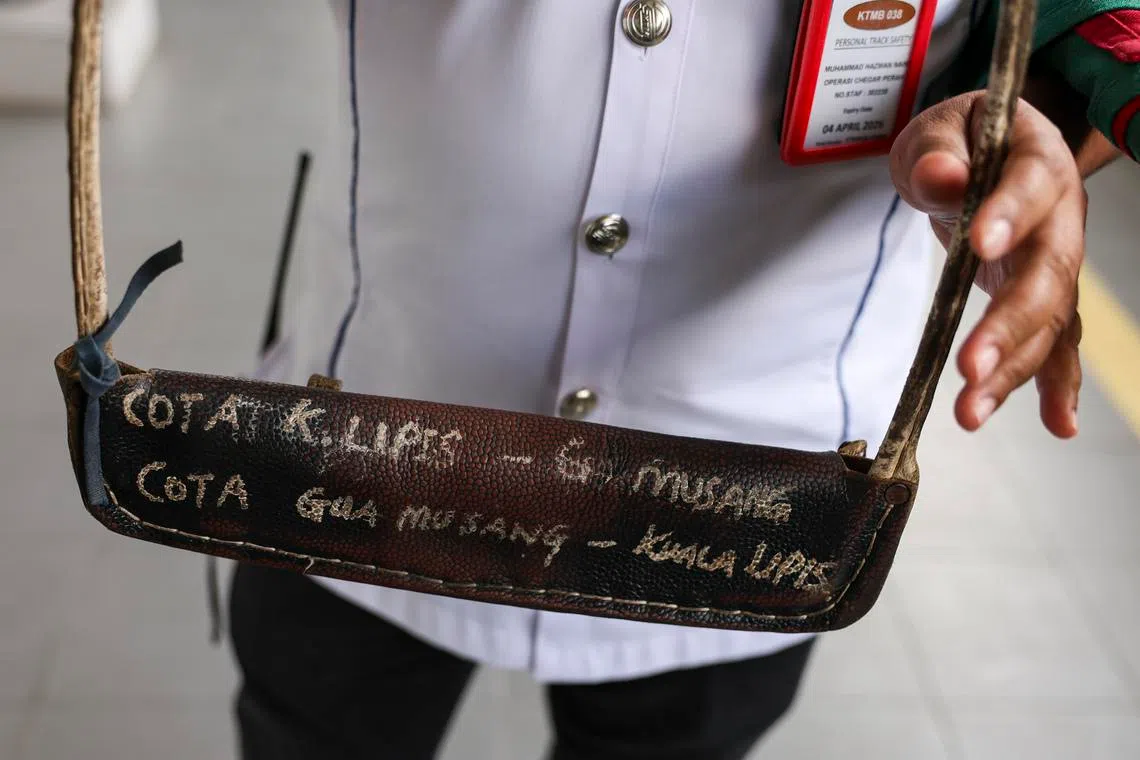

Kuala Lipis station master Muhammad Hazman Naim Hasan, 33, holding the key token which signifies clearance.

ST PHOTO: BRIAN TEO

There is, however, some hope that this relic of the past might be preserved – at least for now.

Mr Afzar said the use of the token system is still relevant for the operational needs of the single-track eastern railway to ensure the “safety and coordination of train movements”.

“Even though rail systems and equipment have evolved according to the times, the foundation of the one train, one token, one block at a time token system is still being used. This is to ensure safety in railways that have yet to transition fully to modern electric signalling systems,” he said.

Sign up for our weekly Asian Insider Malaysia Edition newsletter to make sense of the big stories in Malaysia.