Citizenship for foreign talent: How this footballer from Brazil became Vietnam’s favourite ‘Son’

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

Nguyen Xuan Son, or Rafaelson Fernandes, salutes wearing the Vietnam national team colours.

PHOTO: NGUYEN XUAN SON

Follow topic:

- Brazilian-born striker Rafaelson or Nguyễn Xuân Son's journey from rural Maranhão to Vietnam’s premier football league mirrors the country’s embrace of skilled foreign talent as it moves to modernise the nation.

- Vietnam amended its nationality law, effective from July 1, 2025, to ease citizenship for skilled foreign workers. In addition, dual citizenship is now permitted to attract global talent.

- The South-east Asian nation faces a brain drain but efforts to attract foreign talent and overseas Vietnamese raises concerns about the quality of migrants.

AI generated

HANOI – As the final whistle blew at Bangkok’s Rajamangala Stadium in January, and cheers of victory erupted for Vietnam’s third Asean Championship title, the star of the show – Brazilian-born striker Rafaelson Fernandes, also known as Nguyen Xuan Son – was noticeably absent, having been stretchered away earlier due to a serious leg injury.

But his heroics had already lit the path to triumph: The 1.85m-tall striker powered his way to seven goals in his international debut, an unrelenting presence on the pitch with a fighting spirit that galvanised the team – earning him the Most Valuable Player and Top Scorer awards at the end of South-east Asia’s top international football tournament, and winning him more new fans in his adopted country.

“I am blessed to become a Vietnamese citizen,” Son, 28, told The Straits Times in July from Bahia, Brazil, where he was undergoing rehabilitation. He is expected to resume training in September and return to action in early 2026.

Born in Maranhao state in north-eastern Brazil, the professional footballer moved to Vietnam in December 2019 and signed with local premier club Nam Dinh FC the following year. Less than five years later, he was a naturalised Vietnamese citizen representing the national team, just one of two to do so.

Moving from wintry Denmark where he was living since April 2019 to hot and humid Vietnam after a 14-hour flight, the curly-haired striker recalled the warm welcome from the Vietnamese people, including his club teammates, from day one.

“I feel such a connection with the people in Vietnam,” he said. “I believe my heart is Vietnamese. I play for the team like a (true) Vietnamese person.”

Granting citizenship to foreign-born talent like Son is part of the government’s broader effort to modernise the country and attract investments.

Vietnam amended its nationality law effective from July 1, 2025,

The new law also allows Vietnamese citizens living abroad and foreigners to hold dual citizenship, removing the previous requirement to renounce foreign nationality for those seeking Vietnamese citizenship.

The change in nationality law is seen as the first step in attracting more foreigners to live and work in Vietnam.

Striker Son is one of the most recognisable faces among football-mad Vietnam’s newly minted citizens. His tally of 40 goals makes him the local league’s top scorer for 2024.

While he initially struggled with the local climate, he has since settled down well in Vietnam, along with his wife – fellow Brazilian Marcele Seippel – and two young sons. They live in a rented house in Nam Dinh city, and neighbours have grown accustomed to seeing the Son family members riding around on a scooter, or enjoying their favourite banana fritters from a roadside stall.

Foreign-born talent like Son are among the reasons behind Vietnam’s recent move to amend its law on nationality, aimed at boosting its skilled workforce, in line with the National Strategy on Attracting and Applying Talent to 2030.

The country’s Parliament, known as the National Assembly, swiftly passed the amended law, which creates more flexible conditions for foreign investors, scientists and other highly skilled workers seeking Vietnamese citizenship.

Nguyen Xuan Son and his wife Marcele Seippel, who is wearing the Vietnamese traditional dress called an ao dai.

PHOTO: NGUYEN XUAN SON

No doubt the authorities are keen to boost the country’s skilled workforce in the longer term, given the shrinking birth rate for the South-east Asian nation, which has a population of about 100 million.

Vietnam recently abolished a longstanding policy limiting families to having no more than two children as the nation grapples with a declining birth rate – posing a demographic crunch that could undermine future growth prospects. Under the new regulation approved by the National Assembly Standing Committee in Hanoi on June 3, couples will now have the right to decide when to have children, how many to have, and the spacing between births, the official Vietnam News Agency reported.

The Vietnamese authorities are working on a law on population, but its population policy experts predict that by 2039, the country will reach the end of its “golden population” period, which is defined by the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) as having 30 per cent of the population aged below 14, and 15 per cent of the total aged 65 or above.

This means that Vietnam will have fewer working-age people and more in retirement age, which can lead to an onerous burden on society. Vietnam stands third in the region, after Thailand and Singapore, for the proportion of population aged 65 and over, while its income per capita ranks only sixth in the region.

Amended law permits dual citizenship

According to the new nationality law, individuals who “have made significant contributions to Vietnam’s development and defence, or whose naturalisation benefits the Vietnamese state”, can bypass language proficiency and other minimum residency requirements.

Such individuals do not need to speak fluent Vietnamese. They are also not required to be currently residing permanently in Vietnam or to have lived in the country for five years or more at the time of applying for citizenship.

Additionally, those with a spouse or child who is a Vietnamese citizen, or those with a parent or grandparent who is a Vietnamese citizen, are all eligible to apply for citizenship under the same conditions.

One of the most significant amendments, however, is that the law permits dual citizenship, meaning applicants no longer have to renounce their foreign nationality. Vietnamese-only nationality is still required for government officials, members of the military and security personnel.

Some South-east Asian countries such as Thailand, Cambodia and the Philippines generally allow dual nationality, based on criteria like family ties, descent, local language and residency requirements.

Despite his limited command of the local language, Son became a Vietnamese citizen in September 2024 – before the nationality law was amended – as the footballer was deemed by government officials to be a special case, thanks to his athletic talent and avid fan base.

While he has no official fan club, there are several Nguyen Xuan Son Facebook pages, each with a few thousand followers and as many likes for every post, and his Instagram account has around 140,000 followers.

In response to occasional sledging from opposing clubs’ players and supporters during matches, calling him not a “real Vietnamese”, the footballer who insists he has a “Vietnamese heart” responds good-naturedly with smiles and the V-sign hand gesture – for Vietnam and for victory.

Over the last 17 years, since the previous Law on Nationality was passed in 2008, Vietnam has granted citizenship to just 7,014 people, according to the Ministry of Justice. Of those, only 60 were allowed to hold dual citizenship, in cases specifically approved by the state president.

The number is expected to rise with the new law helping to “attract high-quality human resources to contribute to the country’s development in the new era,” said Justice Vice-Minister Nguyen Thanh Tu in July.

The amended nationality law also aims to facilitate the regaining of Vietnamese citizenship, stipulating that any individual of Vietnamese descent without Vietnamese citizenship living outside the country can now apply for citizenship.

This is particularly relevant to the overseas Vietnamese, known as Viet Kieu, who left the country after the Vietnam War (1955 to 1975) and settled overseas, but now wish to regain citizenship for themselves and their descendants.

Recent policy changes relaxing the nationality law and allowing dual citizenship are aimed at drawing the Vietnamese diaspora – along with other skilled foreign talent – to the country, as part of sweeping economic reforms eyeing higher-value industries.

Facing the brain drain challenge

Like many developing countries, Vietnam faces a brain drain challenge, where skilled individuals choose to leave the country or not return home, resulting in a loss of talent and expertise. This trend is concerning for Vietnam’s economic development, especially as it transitions towards a more technology-driven economy.

Vietnamese authorities and observers warn that the brain drain in the country has reached a concerning level. The Vietnam Migration Profile 2023 noted that between 2017 and 2023, over 250,000 Vietnamese were studying overseas. Up to 80 per cent of them chose not to return to Vietnam, opting instead to stay and work in their host countries.

The report, which was released in 2024, estimated that 70 per cent to 80 per cent of self-funded international students do not return to Vietnam after completing their studies, choosing to remain abroad for higher-paying jobs and better benefits.

According to the report, during that same six-year period, nearly 860,000 went abroad for employment under contract, averaging more than 100,000 people a year.

The Vietnamese government estimated that there are roughly six million Viet Kieu living in 130 countries. Around 600,000 of them are highly qualified professionals who should be given incentives to “return to the country to invest and do business, while also promoting the development of science, technology and innovation”, it said.

Dr Son Pham, 40, chief executive and chief scientist of BioTuring, a San Diego-based start-up specialising in bioinformatics, told ST: “One of the biggest challenges in working in Vietnam is the lack of a culture of science and technology innovation… but things need to start somewhere.”

His company, which has been operating in Vietnam for about six years, recently announced an artificial intelligence model that is able to quickly create detailed visualisations of cancerous tumours – an innovation that could greatly improve screening methods for early cancer detection.

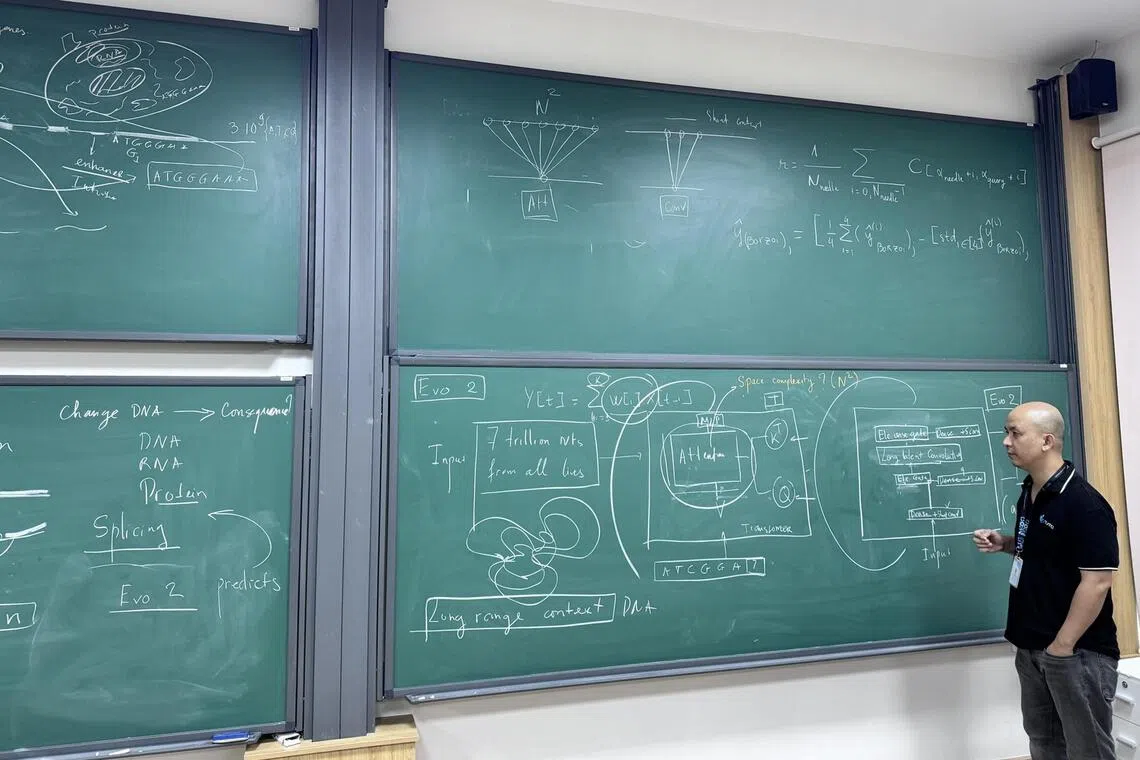

Dr Son Pham delivers a lecture on decoding DNA sequences.

PHOTO: DR SON PHAM

The scientist left Vietnam as a teenager in 1999 to study computer science in Russia, and went on to further his studies on a scholarship in 2008 in the US, where he is based. Dr Son travels regularly to Vietnam for work.

Some other returnees, however, argued that there are still not enough incentives for Viet Kieu talent, some of whom were not even born in Vietnam, to live and work in the country.

“Young people these days care a lot about their living standards – earning a proper salary, having good healthcare and education for their children,” said Vietnamese-American chef and restaurateur Nikki Tran, who returned to Vietnam to open a restaurant in Ho Chi Minh City in 2014. “They don’t come back to Vietnam to pursue an ideology, like in the past.”

The chef, who declined to give their age, left Vietnam as a teenager 30 years ago for the US and returned to “challenge Vietnam’s traditional cuisine principles and present Vietnam’s street food, but not as you know it”.

Chef Nikki Tran has appeared on several Netflix food shows including Street Food Asia, Ugly Delicious and Somebody Feed Phil.

PHOTO: NIKKI TRAN

Worries about lax standards with the new law

The new nationality law amendments are but small initial steps, and Vietnam needs to develop a broader strategy to attract skilled labour, both foreign and Viet Kieu, said Dr Giang Thanh Long, director of the Institute of Public Policy and Management at the National Economics University in Hanoi.

“More importantly, it is about creating the kind of environment they’d want to work in, such as the jobs themselves, the working conditions, and opportunities for personal development,” Dr Long said.

In his opinion, Vietnam can learn from China, which suffered from brain drain in the 1980s. The situation reversed in the early 2010s, as Beijing significantly improved the conditions offered to overseas talent.

There are no statistics yet on new applications since the amended nationality law came into effect, but a few foreigners living in Vietnam who spoke to ST said they were keen to apply for Vietnamese citizenship should the opportunity arise.

With Vietnamese passports, foreign nationals will no longer need a work visa and will gain full access to property ownership and banking services currently available only to Vietnamese citizens.

Some critics say the relaxed regulations, if not closely controlled, could open the floodgates to lower-quality migrants. A local official based in Hanoi, who declined to be named as he was not authorised to speak to the media, said there have been cases of foreigners marrying Vietnamese women in order to obtain citizenship.

“It’s not a big problem yet, but it could become a serious issue in the future if there are more and more foreigners coming to live in Vietnam,” he told ST.

Yet, there are many cases of foreigners who genuinely fall in love with Vietnam and its people, and want to stay in the country for the long term.

In 2023, there were about 19,000 marriages registered between locals and foreigners, up nearly 36 per cent from about 14,000 in 2022.

Mr Hasan Dogan, a 36-year-old marketing executive from Turkey, is learning Vietnamese. He would very much like to settle down in Vietnam, where he has lived and worked for the past five years, but does not believe he has the significant skill set to qualify for citizenship. For now, he sees only one option in order to remain here: marriage.

“Maybe I’ll meet a nice Vietnamese woman and start a family with her – who knows,” he said, with a grin.

Nga Pham is a multimedia journalist in Hanoi, with over 15 years’ reporting experience in South-east Asia.