Ancient traditions grow new roots: Monks in Thailand bring faith to fight against deforestation

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

Thai monks holding saplings as they walked around a temple building at Wat Pasukato in north-eastern Thailand on July 10 to mark Asalha Bucha, a sacred Buddhist holiday.

PHOTO: KIM JUNG-YEOP

- Thai "forest monks" are swopping offerings of candles and incense for saplings in a bid to fight deforestation.

- Across South-east Asia monks are employing creative conservation methods into rituals, like ordaining trees, leading reforestation drives, and using recycled materials for robes.

- Thailand's conservation efforts, alongside governmental policies, have shown improvement and stabilised forest cover.

AI generated

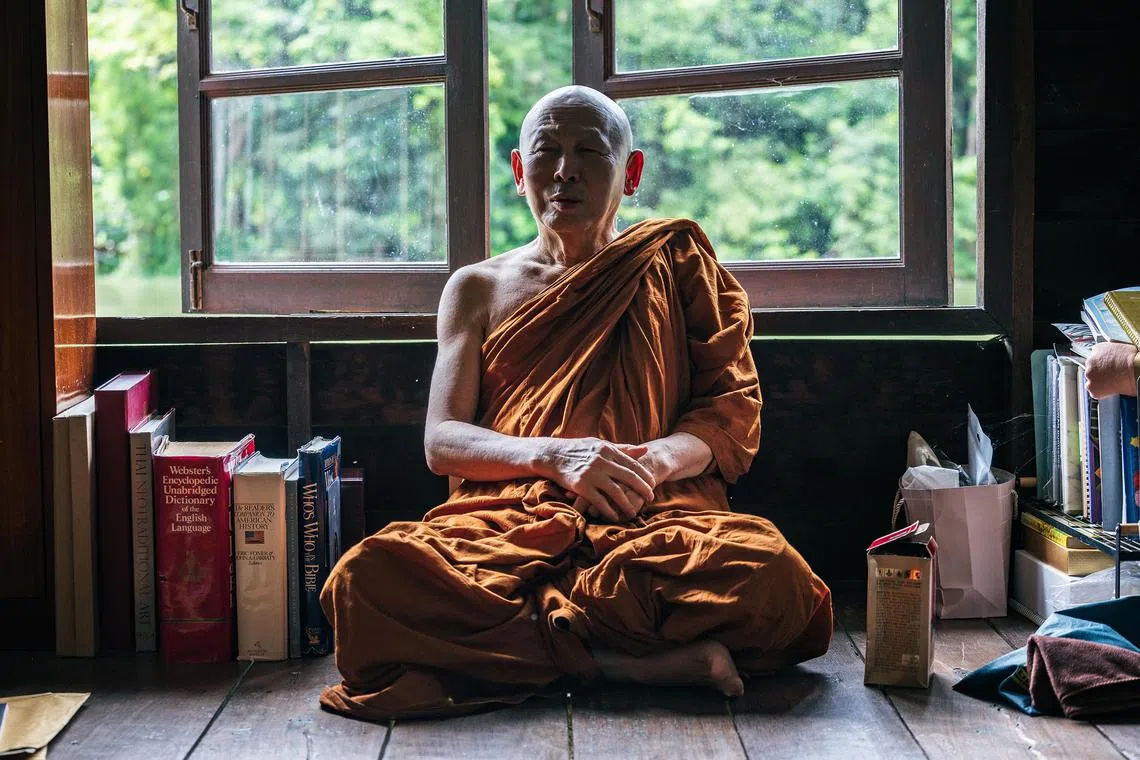

CHAIYAPHUM, Thailand – At dusk on July 10, monks at Wat Pasukato temple in north-eastern Thailand gathered for a quiet procession to mark Asalha Bucha, a sacred Buddhist holiday that commemorates Buddha’s first sermon more than 2,500 years ago.

The group of about 20 saffron-robed monks each carried a plant sapling. Walking three times around the temple’s main building, they chanted prayers – not only for spiritual awakening but also for the earth. Each round took the group roughly three minutes to complete.

“It is our duty to protect the forest,” said Venerable Paisal Visalo, abbot of Wat Pasukato and founder of Trees for Dharma – an organisation of Thai monks advocating reforestation and forest preservation. He was among the monks who took part in the procession.

He added: “The forest is the source of Thai culture and livelihood. Once the forest is protected, the livelihood of the villagers is also protected.”

The ceremony in Chaiyaphum province, just over five hours’ drive from Bangkok, is part of a growing movement in Thailand where “forest monks” are linking Buddhist practice with environmental activism.

For Asalha Bucha in 2025, monks at more than 90 temples across Thailand, including several in Bangkok, swopped candles and incense – typical offerings for the festival that are usually thrown away after one use – for young plants.

At Wat Pasukato, more than 100 saplings of plants, such as avocado, guava and ficus, were prepared. Ecology experts had carefully selected species suited to the region’s climate and biodiversity.

After the ceremony, monks and villagers took the saplings home to plant.

Much of northern Thailand, including Chaiyaphum, has suffered from deforestation linked to monocrop farming, logging and mining. A nearby wind farm built along an ecological corridor has also disrupted local biodiversity, say some monks from temples in the Chaiyaphum region.

Thai monks holding saplings as they walked around a temple building in Wat Pasukato to mark Asalha Bucha commemorating Buddha’s first sermon.

PHOTO: KIM JUNG-YEOP

Thailand lost over 6,000ha of forest in 2024 alone, according to Global Forest Watch, driven largely by land grabs and agricultural expansion.

In the hopes of making up for such losses, villagers, local students and devotees joined in for the July 10 event, some barefoot on the temple grounds, walking behind the monks with saplings in hand.

“The ceremony with the trees seems more active,” said Ms Sukanda Kruda, a local teacher in her 20s. “This year, I came with my nephews and niece.”

Religion meets climate reality

Thailand is not alone in this fusion of faith and environmental consciousness. Across South-east Asia, religious communities are reinterpreting rituals to meet the urgency of the climate crisis.

South-east Asia is home to almost 15 per cent of the world’s tropical forests, making it all the more alarming that the region has some of the highest deforestation rates in the world, losing 1.2 per cent of its forests annually.

To combat this deforestation crisis, Buddhist monks across the region have come up with creative methods to protect the environment.

In Vietnam’s Lam Dong province, one temple is built entirely from recycled material. Meanwhile, monks in Yangon, Myanmar, have participated in large-scale protests against the construction of dams. In Cambodia’s Oddar Meanchey province, village monks are often the last line of defence against illegal loggers, patrolling their towns day and night.

Thailand’s grassroots conservation efforts, alongside governmental policies to ban logging practices, have stabilised the country’s forest cover at around 38 per cent, according to data from the World Bank. This figure has increased from about 25 per cent in the 1990s. Meanwhile, Vietnam saw a 3.7 per cent increase in its forest coverage in 2024, according to the country’s statistics authority.

What unites these efforts is a view of nature not as a resource to exploit, but as something sacred. In Theravada Buddhism, the dominant form of Buddhism in Thailand, forests hold special significance due to their connection to Buddha.

“Buddha was born, found enlightenment and died under a tree,” said Venerable Dhamma Caro, whose Wat Pa Mahawan forest temple in Thailand’s ecological corridor in the north-east has spent decades reforesting and protecting the area. “Even for meditation, the tree is important. The loss of a forest is an environmental problem, but also important to Buddhism.”

Thailand’s forest monk tradition dates back centuries, with monks historically retreating into the woods for ascetic practice. Today, they remain guardians of forests – not just for spiritual reasons, but also to address ecological collapse.

Wat Pasukato’s abbot Paisal Visalo speaking to The Straits Times in Chaiyaphum in north-eastern Thailand.

PHOTO: KIM JUNG-YEOP

The activism takes many forms. Some monks ordain trees – wrapping orange robes around trunks and declaring them sacred. Others lead reforestation drives, teach ecological ethics in sermons or recycle plastic to create robes.

Still, challenges persist – dwindling religious populations and lack of government policy support.

“There seems to be less respect given to the robe these days,” said one such forest monk who has been reforesting trees in Thailand’s north-eastern region for the last decade. He declined to be named for fear of backlash. “Some businesses disregard our efforts.”

New ways of making merit

Replacing candles with saplings on holy days is a relatively recent addition, first proposed by Ven Visalo around five years ago. But the symbolism is powerful.

In Buddhism, planting trees generates merit and represents compassion in action. For devotees, the ceremony offers a tangible way to give back.

Wat Pasukato alone has reforested an area of approximately 1.5 sq km since the late 20th century. Other temples across Thailand have followed, planting trees on temple grounds and lands donated by the faithful.

“Planting the tree not only helps people, but it also helps the animals, and the overall environment,” said another monk who was part of the procession and did not want to be named as he wanted to steer clear of the public spotlight. “That is why it generates merit.”

Ven Visalo said: “In Buddhism, internal peace and external peace are not separate. If we want to find peace in ourselves, we need to work for the sake of society and the environment.”

He added: “For internal peace to be possible, we have to enable and develop peace in the environment around us.

“The less selfish we are, the more peace we achieve in our mind.”

The ceremony at Wat Pasukato was a first for some younger monks.

“It’s a first and new experience for me, so it’s pretty interesting,” said Venerable Huy, a Vietnamese monk ordained just five days before Asalha Bucha. “Forest means nature, and nature is dharma. So, to advocate for forests and reforestation is to protect nature, and to advocate for Dharma.”

In Buddhism, Dharma is an encompassing term, referring to the teachings of the Buddha, the cosmic law and order, and the path to enlightenment.

As the sun set behind the temple’s silhouette, monks and villagers carried their saplings home – quiet reminders that even ancient traditions can grow new roots.