Philippines v China in the South China Sea: All you need to know ahead of The Hague ruling

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

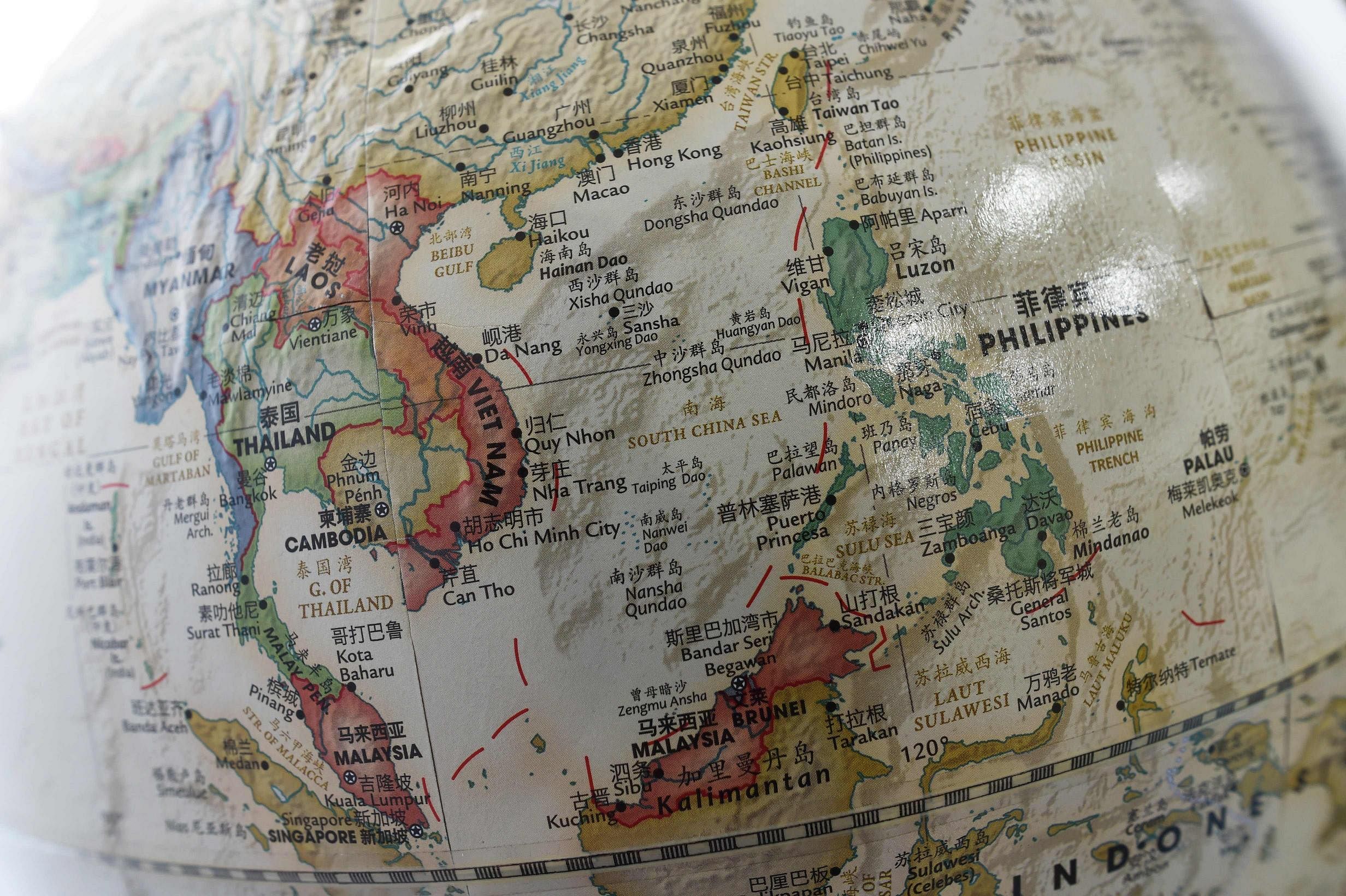

Activists hold up signs during a protest over the South China Sea disputes outside the Chinese Consulate in Makati City, Metro Manila on June 12, 2015.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Follow topic:

On July 12, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague will hand out its judgment on a case lodged by the Philippines challenging China's claims in the South China Sea.

The PCA is an intergovernmental organisation that organises arbitral tribunals to resolve disputes among its 121 member states.

Its ruling on the Philippines-China dispute will be much scrutinised not just by the two nations involved but also their neighbours in East and South-east Asia, as well as the United States.

WHAT IS AT STAKE HERE?

The 3.5 million sq km South China Sea is critical to the world’s economy and to regional security.

These waters cover over 250 islands, atolls, cays, shoals, reefs and sandbars, mostly uninhabited and either partially or wholly underwater.

Some US$5 trillion (S$6.6 trillion) in ship-borne goods pass through the South China Sea each year, connecting Asia’s fast-growing economies with the US, Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

The South China Sea is also believed to hold reserves equivalent to 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.

The US is concerned that China, if left unchallenged, may seize control of these vital international shipping lanes and resources with a chain of man-made islands it has been creating across the South China Sea. Most of these islands have airstrips, harbours and other structures meant to support the Chinese military and extend its reach.

China was not the first to station troops or reclaim land in the South China Sea.

The Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia and Taiwan have all built airstrips on the disputed islands under their control.

Vietnam has five tanks on Spratly island, Taiwan has about 500 soldiers securing Itu Aba, while the Philippines has a contingent of Marines securing a community of some 200 civilians on Thitu Island. Malaysia has transformed Swallow Reef into a resort island.

But what has raised red flags is China's recent surge of activity - it has reclaimed 17 times more land in 20 months than the other claimants combined over the past 40 years, accounting for 95 per cent of all reclaimed land in the Spratlys.

Defence analysts believe Beijing may soon deploy warplanes and missiles to islands it has built on reefs it occupies in the Spratlys archipelago, near the Philippines, as it prepares to control the airspace above the South China Sea and disrupt “freedom of navigation operations” by the US and its allies.

Ultimately, the case is a test for both the US and China, how these two super-powers can co-exist and maintain peace in the fastest-growing corner of the world.

For the US, it will be a test of its credibility as an ally and whether its friends in Asia can continue to rely on it to maintain stability to the region.

For China, the ruling will be a test of how as a rising regional power it is willing to be bound by a tribunal sanctioned by existing international law.

WHAT IS THE CASE ALL ABOUT?

While the specifics of the case goes into maritime rights conferred by the disputed rocks and reefs, in essence it is also about the challenge posed by China’s “nine-dash line”.

SO WHAT IS THE NINE-DASH LINE?

The nine-dash line marks the boundaries of China’s claims over the South China Sea. It was first drawn as an 11-dash line by cartographers of the Kuomintang regime in 1947.

It covers nearly all of the South China Sea; over 2 million sq km of it. It protrudes from China’s southern Hainan island, loops 1,611km away towards Indonesia, and then links back to the mainland in a cow-tongue shape.

WHAT'S THE ISSUE WITH THIS NINE-DASH LINE?

The nine-dash line overlaps with some 531,000 sq km of waters that the Philippines considers part of its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and extended continental shelf.

An EEZ is a United Nations-adopted concept that grants a coastal state exclusive rights to explore for and exploit marine resources inside a band extending 200 nautical miles (370km) from its shore.

The nine-dash line also overlaps with territories in the South China Sea claimed by Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and Taiwan.

WHY IS CHINA CLAIMING NEARLY ALL OF THE SOUTH CHINA SEA?

China has refused to clarify the exact geographical coordinates of the nine-dash line, or say whether it considers the South China Sea to be Chinese territorial waters, an EEZ or some other legal designation.

It has instead used historic facts and ancient maps to support its claims. It cites extensive records of visits, mapping expeditions and habitation from the Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD), right through the modern period.

China also contends that the 1943 Cairo conference, 1945 Potsdam conference and 1951 San Francisco peace treaty - all held under the auspices of the US, Britain and Russia - restored to it territories taken by Japan, including the Paracel and Spratly archipelagos in the South China Sea.

WHAT IS THE PHILIPPINES' MAIN ARGUMENT AGAINST THE NINE-DASH LINE?

The Philippines contends that the nine-dash line is inconsistent with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos).

WHAT IS UNCLOS?

Unclos, a treaty the Philippines ratified in 1986 and China in 1996, outlines a system of territorial and economic zones that can be claimed from continental shelfs, islands, islets, shoals, reefs, atolls, cays, sandbars, and other rocky outcrops.

Unclos allows a nation to:

- Exercise sovereignty over waters 12 nautical miles from its coast;

- Exercise economic rights over waters on a nation's continental shelf, and up to 200 nautical miles from its coast, that is the EEZ.

But it says reefs that are entirely submerged at high tide cannot be used to justify any maritime rights.

Unclos cannot be used to determine who owns what land; in other words, it cannot determine sovereignty.

The Philippines has been careful to frame its complaint in a way that sidesteps the question of who has sovereignty over the islands and reefs.

That is why the 4,000-page, 10-volume plea on the South China Sea that it submitted to the PCA in 2014 reads more like a lengthy dissertation on geography, geology, and topography, rather than a legal brief.

WHY IS THE PHILIPPINES CLAIMING THAT THE NINE-DASH LINE IS INCONSISTENT WITH UNCLOS?

The Philippines argues that under Unclos, the nine-dash line has to emanate from land, not from historic rights or ancient maps.

It says there is no land mass or clumps of islands and rocks in the South China Sea that are large enough to generate maritime or economic rights that can encompass the 2 million sq km that the nine-dash line spans.

It says there is no land mass or clumps of islands and rocks in the South China Sea that are large enough to generate maritime or economic rights that can encompass the 2 million sq km that the nine-dash line spans.

The South China Sea is mostly sea. Most of the over 250 islands, atolls, cays, shoals, reefs and sandbars there are uninhabitable rocks that do not even break the surface of the water, even at low tide.

Without land that can generate maritime rights, the nine-dash line does not have legs to stand on, the Philippines argues.

In the Spratly archipelago in the southern half of the South China Sea, China controls seven reefs: Subi, Gaven, Hughes, Johnson South, Fiery Cross, Cuarteron and Mischief.

The Philippines says at most, these reefs – being either partly or mostly submerged at high tide – can each claim a boundary of just 12 nautical miles under Unclos. This is the most that China can claim, it says, not 2 million sq km.

China has dredged rock and sand to transform the seven reefs into islands. (Islands, under Unclos, are entitled to a 200 nautical mile EEZ.)

But the Philippines insists Unclos also does not confer maritime rights to artificial islands.

An atoll north of the Spratlys known as Scarborough Shoal, in Chinese hands since 2012, meanwhile, generates only “territorial sea”, says the Philippines. The rocks are visible even during high tide, but the shoal, too, cannot be used as an anchor for the nine-dash line, it says.

KEY POINTS OF CONTENTION AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS

If the tribunal court decides that maritime rights emanate from land and not from historic rights or ancient maps, it will, by extension, be declaring that the nine-dash line is invalid.

That reduces the scope of the dispute to the Spratlys.

The only other land feature outside the Spratlys covered by the Philippines’ case is Scarborough Shoal. The atoll’s 12-nautical mile territorial sea does not overlap with any other rocky outcrop. The only overlap is with the nine-dash line. If the line is declared void, then there will be no dispute over Scarborough’s borders as these would not be overlapping with anyone else’s.

But in the Spratlys, the reefs, shoals, and islands there are being occupied not just by China and the Philippines, but also by Vietnam, Taiwan and Malaysia.

The tribunal will have to determine the maritime rights of all rocky outcrops there. It has to determine which land features are entitled to 12 nautical miles, 200 nautical miles, or not entitled to anything at all.

One land feature that is proving problematic for the Philippines is the 48ha Itu Aba, which Taiwan occupies.

Taiwan has filed an intervention in the Philippines’ case to argue that Itu Aba, 2,000km south of Taipei but just 416km west of the Philippine island province of Palawan, is an island entitled to a 200-nautical mile EEZ, which extends all the way to Palawan’s coasts.

The Philippines, on the other hand, insists that Itu Aba, despite its size, cannot be considered an island under Unclos because it lacks a naturally occurring source of fresh water that can sustain a small population.

If the arbitration court rules that Itu Aba is not an island, then no other rocky outcrops in the South China Sea can be considered an island.

In any case, Itu Aba, even if it is declared an island with a 200 nautical mile EEZ, cannot, on its own, justify China’s nine-dash line.

WHY IS CHINA NOT PARTICIPATING IN THE PROCEEDINGS?

China insists that the Philippines is seeking a determination of who owns what in the South China Sea; in other words: sovereignty.

Sovereignty, it argues, falls under the purview of the International Court of Justice, not the arbitration court convened under the auspices of the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (Itlos), and any case involving sovereignty will require its consent.

China has been consistent in claiming “indisputable sovereignty” over the South China Sea.

It insists that it can reject compulsory arbitration on “maritime delimitation” – essentially a determination of sea borders – under a 2006 UN declaration.

It insists that it can reject compulsory arbitration on “maritime delimitation” – essentially a determination of sea borders – under a 2006 UN declaration.

The arbitration court has rejected these arguments.

WHAT HAPPENS IF THE COURT RULES IN FAVOUR OF CHINA?

Should the Permanent Court of Arbitration recognise China’s historic rights and ancient maps and affirm the nine-dash line, the ruling will technically give China legal ground to use force to push its rivals out of the South China Sea.

Such an outcome would deal a severe setback to the US in its geopolitical contest with China and increase Beijing's dominance of the region.

Analysts, though, believe this is the most unlikely outcome.

WHAT HAPPENS IF THE COURT RULES IN FAVOUR OF THE PHILIPPINES?

The arbitration court may decide that China cannot use its historic rights and ancient maps to justify the existence of the nine-dash line.

It may also agree with the Philippines that maritime rights emanate from land, and that none of the rocky outcrops in the South China Sea, including Itu Aba, can be considered islands. This being the case, disputes will be limited to smaller areas involving rocks, with maritime rights limited to 12 nautical miles.

While it would be a deadly blow to China's claims, Beijing is more likely to dig in and fortify its holdings in the South China Sea, rather than comply.

Again, this scenario will likely lead to an escalation of tension and raise the risks of conflict in the region.

HOW ELSE CAN THE TRIBUNAL DECIDE ON THE CASE?

Most observers believe the arbitral tribunal is unlikely to rule fully in favour of the Philippines or China.

It will most likely declare the nine-dash line as inconsistent with international law, but it may decide on maritime rights in the South China Sea in a way that may open other avenues for more discussions.

Here are three more possible rulings:

1. Everything above water at high-tide is an island entitled to a 200 nautical mile EEZ.

This will lead to a massive overlap of maritime boundaries as most of the disputed land formations in the Spratlys are clumped close together. Overlapping boundaries will have to be resolved via compulsory conciliation, again with Unclos as guide, but with a different set of judges. With the reefs it controls in the Spratlys, China can lay claim to a large swathe of the South China Sea, though it may be smaller than the area covered by its nine-dash line, and engage claimants individually in resolving border overlaps.

2. The smallest features, including Scarborough shoal, are rocks that get a 12-mile boundary and territorial seas.

The court will leave open for discussion whether the larger land features - particularly those with vegetation – can be considered islands with a 200-nautical mile EEZ. That will still leave a very large area in dispute, and may yet give China’s artificial islands an EEZ, but it will at least put everyone on the same page as to how claims should be made under Unclos. Again, it opens up a path to negotiations with China.

3. Everything in the South China Sea are rocks, except Itu Aba.

The tribunal may dismiss the Philippines’ claim that Itu Aba is not an island because it does not have naturally occurring freshwater. (Taiwan has been mounting a media campaign to show that Itu Aba does indeed have its own water source.)

Itu Aba’s 200-nautical mile EEZ will be recognised, but its borders will have to be determined via compulsory conciliation, as these will overlap with a large chunk of the Philippines’ south-western border.

Itu Aba’s 200-nautical mile EEZ will be recognised, but its borders will have to be determined via compulsory conciliation, as these will overlap with a large chunk of the Philippines’ south-western border.

This is the ruling most pundits are betting on. This concedes to Taiwan’s position, and reduces the dispute to waters around Itu Aba.

HOW WILL THINGS UNFOLD AFTER JULY 12?

Tensions and rhetoric have been rising ahead of the ruling.

China conducted military exercises around the Paracel Islands in the north of the region this past week, while US destroyers had been patrolling around Chinese-held reefs and islands in the contested Spratly Islands to the south. A carrier group around the USS Ronald Reagan has also been patrolling the South China Sea.

China is unlikely to back down in the face of an unfavourable ruling. It has already said it will not “take a step back”, as it reiterated its position that the court proceedings are a “farce”, and the tribunal’s forthcoming ruling “illegal, null and void from the outset”.

As a push-back, China is expected to declare an air defence identification zone (ADIZ) over the South China Sea and deploy warplanes to its artificial islands in the Spratlys. An ADIZ will require all aircraft flying over the South China Sea to submit their flight plans to Chinese security officials.

China may also attempt to build an island on Scarborough Shoal, a red line as far as the US is concerned, and reimpose a blockade around Philippine troops stationed at a beached World War II transport ship on Second Thomas Shoal in the Spratlys.

The US response will likely be to step up freedom-of-navigation patrols close to Chinese-claimed islands, as it rallies its allies to compel China to respect the tribunal’s ruling.

It may send its warships to waters just beyond 12 nautical miles off China’s islands to assert rights of sovereign states to sail their ships, without interference, in international waters.

Pressure may come from Vietnam, another claimant to parts of the South China Sea, which may file its own case for arbitration.

Even non-claimants like Indonesia may take advantage of the ruling to discourage China from encroaching on uncontested waters.

Even non-claimants like Indonesia may take advantage of the ruling to discourage China from encroaching on uncontested waters.

Japan is also expected to send more ships to the South China Sea to support the US’ freedom-of-navigation patrols.

HOW WILL THE OUTCOME AFFECT ASEAN?

The row has driven a wedge into Asean. China has succeeded twice in preventing Asean from issuing a joint statement critical of its more assertive posture in the South China Sea.

In 2012, the Philippines and Vietnam had insisted on including references to their territorial disputes with China in a communique, but Cambodia blocked it, ending that year’s foreign ministers’ meeting without a joint communique for the first time in Asean’s 45-year history.

Last month, in a meeting hosted by China in Kunming, Asean’s foreign ministers signed off on a joint statement expressing “serious concerns over recent and ongoing developments, which have eroded trust and confidence, increased tensions and which may have the potential to undermine peace, security and stability in the South China Sea”.

But the statement was not released to the media, after Laos and Cambodia objected to it.

Still, Malaysia leaked the statement, only to retract it hours later.

Asean will have to decide now what to do with the ruling.

The US has been pressing the group to issue a strong statement telling China that the arbitration court’s ruling is binding. That is, however, unlikely.

Ironically, the Philippines itself, which lit the fuse but is now under a new, Beijing-friendly president, has advised against any statement that will be “provocative”.

Analysts are expecting that after the initial fireworks following the ruling, Asean will try to find a way to get China on the same page to bring some semblance of peace and stability in the South China Sea.