BRANDED CONTENT

The University of Tokyo is reminding the world to save our planet

Its Center for Global Commons aims to provide the necessary stewardship to expedite protection of the world’s land, oceans, biodiversity and beyond

PHOTO: THE UNIVERSITY OF TOKYO

Follow topic:

Fact: We only have 10 years left to reverse global environmental damage, and hand a healthy planet over to the next generation.

The world's global commons - shared resources such as oceans, biodiversity and land that are foundational to human and other lives - remain under attack by greenhouse gas emissions, pollution, overfishing, harmful agriculture and other unsustainable practices.

To draw attention to the commons' undervaluation and over-exploitation, as well as their poor and worsening condition, the University of Tokyo is stepping up to effect positive environmental change.

Leveraging its ability to mobilise large-scale social change based on its standing of trust, it established the Center for Global Commons (CGC) last August. The initiative to equip stakeholders with knowledge, policy framing, processes and tools to halt and reverse the degradation of the commons. It also intends to study international stewardship, spur policy debate and transform key socio-economic systems to protect them.

And its online edition of the annual Tokyo Forum event held last December - co-hosted by South Korean knowledge-sharing platform Chey Institute for Advanced Studies - was aptly themed "Global Commons Stewardship in the Anthropocene".

A forum to safeguard the future

The two-day virtual forum, aimed at letting its audience acquire the broad concept of "global commons" in the "Anthropocene", gathered high-level government, business and academic delegates. They included Mr Sunny Verghese, co-founder and chief executive of Olam International; Dr Lee Hoesung, chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; and Ms Helen Mountford, vice-president of climate and economics at the World Resources Institute.

Event highlights were a high-level special dialogue, four panel discussions and a student session, with participants delving into topics such as the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the global commons, and best practices to conserve them.

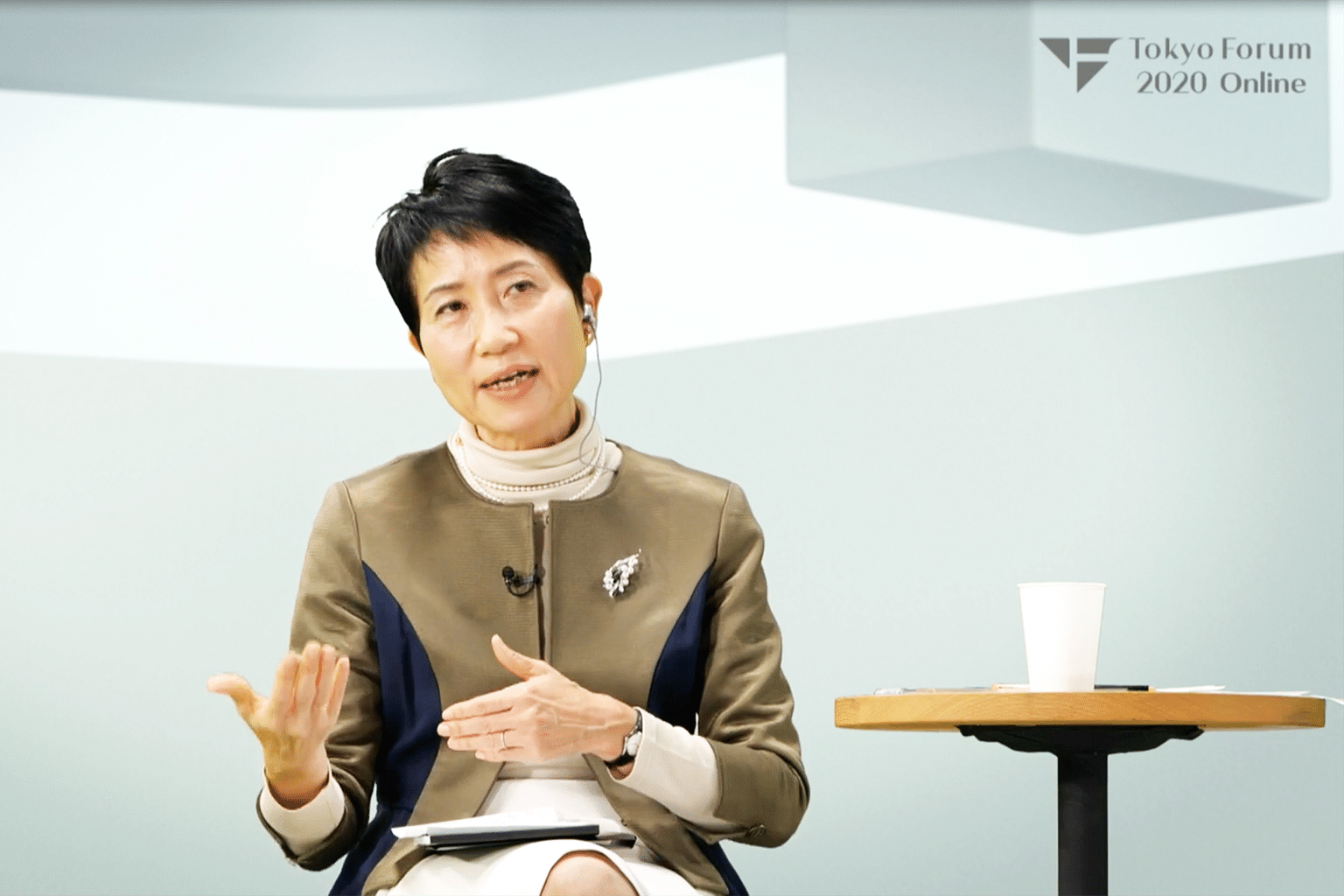

Dr Naoko Ishii, the CGC's director and executive vice-president, was a speaker at the forum. She noted that the attendees recognised the urgency of the fight to defend the commons.

"The narrative has changed over the years. In the past, we didn't want to overwhelm people about the threat to the commons in case they felt frozen and hopeless. But years later, nothing has changed. We decided that we need to make the point much clearer: we have only 10 years left to change our course, or we will fall off a cliff," she says.

Creating opportunities for research and rectification

At one of the four panel discussions held, CGC's pilot Global Commons Stewardship index was showcased.

Designed to be a tool for drawing attention to countries' impact on the commons and for devising better ways to manage them, it consists of six indicator categories: aerosols, biodiversity, land, water, oceans and climate change. In the biodiversity category, for example, the index considers how a country's domestic production and imports threaten terrestrial and freshwater biodiversity, among other factors.

The index also assesses countries' stewardship of the global commons by tracking how they affect the environment and deplete natural resources, both through domestic activities and international impact.

According to Dr Ishii, accounting for the latter is crucial; some countries may try to achieve decarbonisation targets by outsourcing the production of items such as cement and steel which emit high levels of greenhouse gas - only to import these items as final goods.

"Beyond trade-related environmental harms, it is also important to track transboundary physical flows, such as air and water pollution, where production or consumption in one nation spills over onto neighbouring countries and beyond," she explains.

Leveraging data to enable transformations

To date, the index has already discovered several key findings. For example, most developed countries generate large negative impact on the commons, and international spill-overs play a significant role.

Switzerland, for example, emitted six tonnes of carbon dioxide-equivalent per person through domestic activities, but imported 4.8 tonnes per person - which makes up 44 per cent of its total footprint - through the products and services it consumes.

Another key finding is that the world's largest economies - China, the United States, India, Japan, the EU and Russia - cause the greatest absolute negative impact.

The pilot index will continue to be fine-tuned to reduce its data gaps, says Dr Ishii. But she is heartened that it has "sparked plenty of interest, and many discussions about its implications, and what policies need to be taken", and hopes that it will better direct people's decisions in terms of consumption and investment.

Crucial changes for the global commons

Beyond its work on the index, the CGC is collaborating with other institutions on other major undertakings.

These include scenario modelling to show how countries can achieve the sustainable world by 2050, creating methods and policies to catalyse system change, and finding ways to use fast-developing digital technologies and data to accelerate such transformations.

"We are also focusing on how to spread awareness of the global commons, and communicate the need for change to policymakers, companies and citizens. We have the opportunity to change our course, but everybody must work together - governments, businesses, citizens and investors.

"The more science-based data and knowledge people have, the more they can make informed choices. We need a sense of urgency about the task ahead of us. We used to think that we had until 2050 to make a difference, but science is telling us that we only have 10 years to shift our course, if we want to meet our 2050 goals."

Following the forum, plans are in the pipeline to work on the modelling, improve the index and partner with the business to promote systems change. Adds Dr Ishii: "The tide has been changing; the message of urgency has gained a lot of traction. We hope this will help pave a way for stewarding the commons."