Scientist who claims he created genetically edited babies drew backing from China biotech push

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

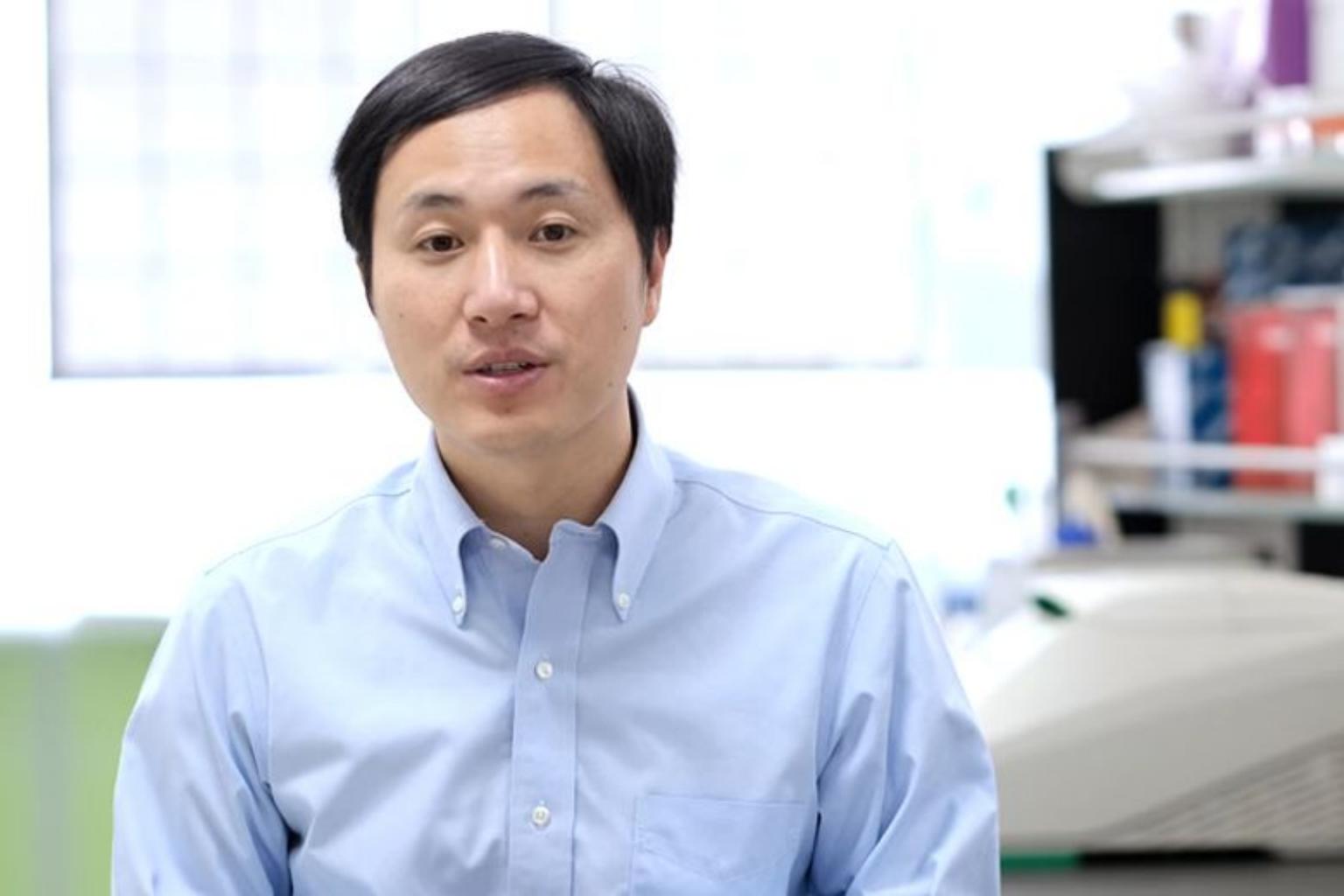

Dr He Jiankui pushed back against suggestions that he had been secretive about his work, saying that he had presented preliminary aspects of it at conferences and consulted with scientists in the US and elsewhere.

PHOTO: SCREENGRAB FROM YOUTUBE

BOSTON (BLOOMBERG) - The researcher who shocked the world with claims that he was the first to genetically modify human embryos drew early support from Chinese government initiatives designed to build up the country's nascent biotechnology industry.

Scientist He Jiankui, who said he edited the genes of twin girls to shield them from HIV, had participated in a programme designed to capitalise on training Chinese nationals get at Western universities.

Additionally, a company that Dr He founded has received government funding. It is not known how much Dr He's experiments cost or how they were paid for.

While it is not uncommon for researchers to have ties to state programmes in China, government officials have sought to distance themselves from Dr He after widespread condemnation from other scientists.

A Chinese official said on Tuesday (Nov 27) that the country prohibited gene editing for fertility purposes in 2003. In the United States and Europe, genetic editing of human embryos is barred.

The news arrived at a sensitive time in Chinese and US relations, with US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping days away from a pivotal trade summit.

China's efforts to nurture homegrown innovation has chafed US officials, who have warned against its talent-recruitment programmes and other support for rivals to important engines of the US economy.

The unfolding controversy over Dr He's research could heighten a battle for global technological dominance between the world's two largest economies.

THOUSAND TALENTS

The "Thousand Talents" initiative was designed to lure foreign-educated researchers back to China to fulfil Beijing's broader desire to become a global leader in high-tech fields. Dr He, who received his PhD from Rice University in Houston and did postdoctoral research at Stanford University, returned to China in 2012 and took part in Thousand Talents.

Participants in the programme with advanced skills receive the equivalent of about US$143,000 (S$197,000), with the possibility of additional research grants of roughly US$700,000, according to its website. They must work in China for more than nine months per year for three consecutive years. It was not immediately clear how much funding Dr He received.

Following his return to China, Dr He also founded a start-up called Direct Genomics that makes a type of DNA-sequencing machine. It too received government funding, according to the company's website.

Representatives for Direct Genomics and Dr He's laboratory did not immediately respond to e-mailed requests for comment.

China's biotechnology industry, which lags well behind the US in terms of approved drugs and global market power, has been one of the beneficiaries of Beijing's generous funding policies and recruitment efforts. A recent regulatory overhaul also has made it much easier to get drugs onto the market in China.

Researchers in China have also become adept at using Crispr, the gene-editing technology Dr He is reported to have used to alter human embryos. It has many potential applications, from agriculture to basic medical research. China is "particularly competitive" in Crispr, said a November report from the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, which oversees national-security risks posed by trade with China. The panel's report highlighted Crispr's potential applications in agriculture.

Alarm in Washington

China has made no secret of its ambitions to become a technological superpower in the 21st century. Its "Made in China 2025" blueprint outlines its plans to become a global player in artificial intelligence, robotics, and biomedical research, among other areas.

Those ambitions have set off alarms in Washington. Last week, US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer's office issued a report accusing China of downplaying its goals while continuing to steal American intellectual property. The report highlighted record Chinese venture-capital investment in the US biotech industry.

However, biotech transactions with Chinese investors are likely to face greater scrutiny. In October, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US announced a pilot programme through which the agency would be able to oversee minority-stake investments by foreign entities in certain critical US industries, including biotechnology.