S. Korea faces increasing complaints of abuse from migrant workers even as reliance on them grows

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

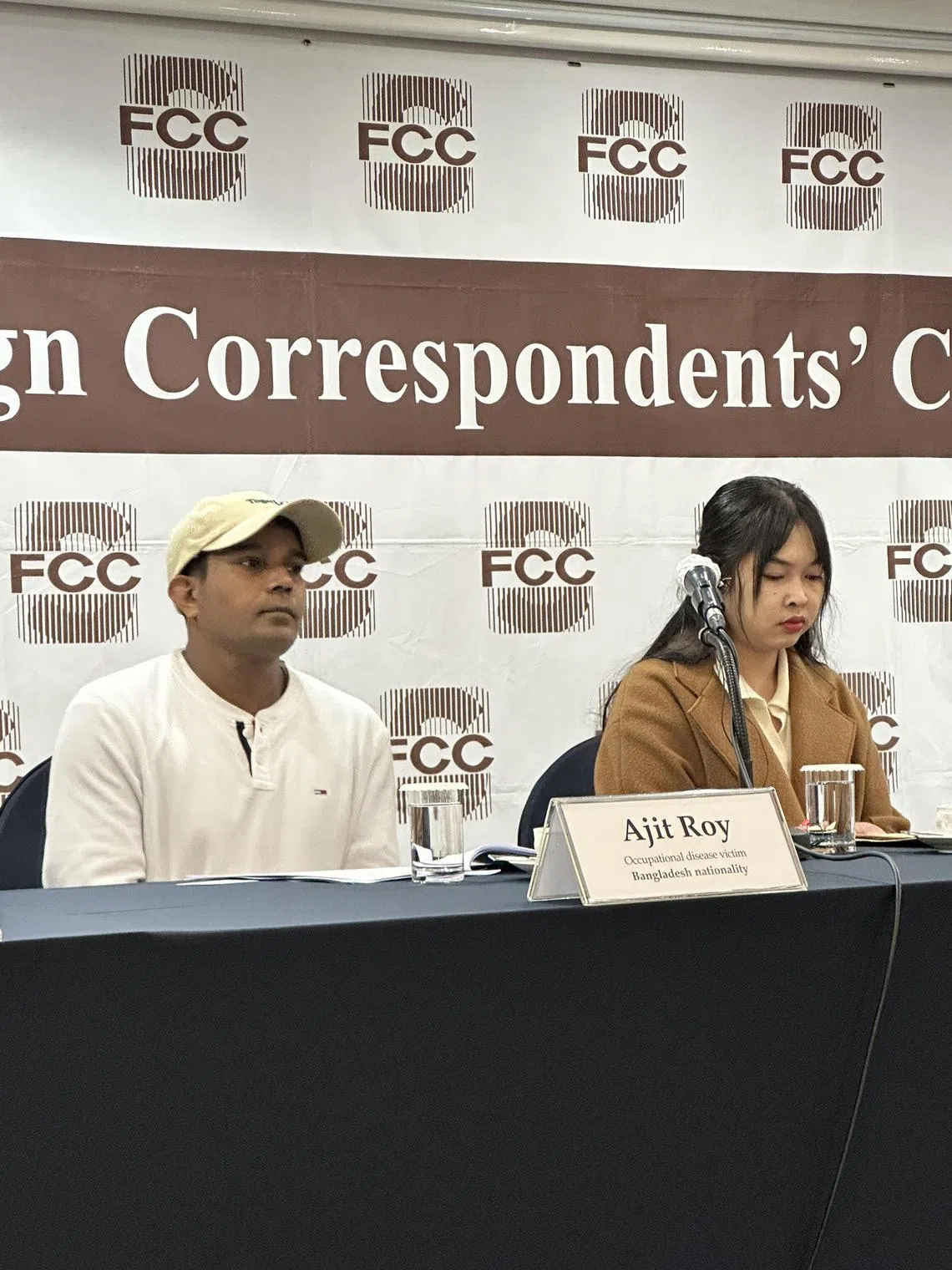

Bangladesh national Ajit Roy was diagnosed with interstitial lung disease eight months after he started work at a South Korean agricultural machinery factory, where his duty was to grind down metal parts.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF AJIT ROY

Follow topic:

SEOUL - Six months after he started work at an agricultural machinery factory in South Korea in 2021, Mr Ajit Roy, who is from Bangladesh, started having a severe cough that would not go away.

His work at the factory in Anseong city, an hour’s drive from Seoul, required him to sand down metal parts for more than eight hours a day, and he was provided with only a cotton mask as protection.

The industrial practice for such a task usually includes hearing protection, safety glasses, a face shield, gloves and flame-resistant clothing.

When Mr Roy finally sought medical attention at a hospital in Seoul after his symptoms became worse and he had trouble breathing, he was diagnosed with interstitial lung disease – an ailment commonly associated with extended exposure to hazardous particles.

The disease causes lung damage that is often irreversible and worsens over time.

After undergoing surgery, Mr Roy is now left with only 60 per cent lung function. He is unable to work and remains in South Korea for treatment. He has been told that the life expectancy for patients like him is four years from diagnosis if he does not undergo treatment.

He is receiving shelter at a church which takes care of his living and medical expenses. In return, he helps to interpret for other migrant workers in need.

Mr Roy, now 39, is among the growing number of foreign workers in South Korea who are helping to plug the country’s labour shortfall caused largely by an ageing population and falling birth rates.

The foreign workers take on low-paid manual jobs in labour-intensive industries such as manufacturing, agriculture and fisheries that are shunned by locals.

But as the number of foreign workers rise – with the yearly quota for new work permits for such workers more than doubling from 60,000 in 2022 to 165,000 in 2024 – a growing number of cases of migrant worker abuse such as that faced by Mr Roy are also coming to light.

Apart from facing discrimination and language barriers, migrant workers are being owed wages, endure poor working conditions and are exploited by job brokers who charge high commissions.

Brokers’ exploitation of workers is so rife that it prompted the National Human Rights Commission of Korea to issue a statement on Nov 5, calling on the government to come up with measures to protect foreign workers from unscrupulous brokers. Foreign workers rely on brokers to find employment in South Korea.

The commission said the current system lacks a central oversight that would better protect such workers.

A coalition of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) held a press briefing for foreign media on Nov 27 to highlight the plight of migrant workers and to push for reform of the foreign labour employment scheme which began in 2004.

Mr Udaya Rai, who heads the migrant workers’ union under the influential Korean Confederation of Trade Unions, said at the briefing: “The scheme has changed a lot over the past 20 years, but most of the changes are favourable to the employers and the pain and difficulties experienced by migrant workers have not improved much.”

South Korea’s migrant worker scheme sources workers from 16 Asian countries including Bangladesh, China, Cambodia, the Philippines and Vietnam, with 560,000 currently in the country.

When Philippine national Mary Kris Omangay came to South Korea in May 2024 for three months of seasonal farm work, she was hoping to earn money to support her youngest sister through nursing school.

The understanding with her broker was that she just needed to transfer half of her monthly salary of 1.28 million won (S$1,228) to the broker as commission, over a period of three months, which Ms Omangay complied with.

But when the 35-year-old’s contract was extended for a further three months, the broker continued to demand the commission, which Ms Omangay felt was too much and refused to comply.

“He threatened to send me back to the Philippines if I do not cooperate,” said Ms Omangay at the briefing.

Cambodian national Thleng Tepy (left) and Filipino national Mary Kris Omangay faced wage issues while working in South Korea. Ms Tepy is claiming back wage arrears to the tune of 29 million won while Ms Omangay is trying to claw back excessive commission paid to her broker.

ST PHOTO: WENDY TEO

She stopped working from September, and has since lodged a complaint with the labour authorities against the broker, to recover the extra month of commission paid.

She is being assisted by the non-governmental organisation 1218 For All that helps migrant workers in need, whose representative Ko Gi-bo told The Straits Times that while the amount is small, the action is about taking steps to stop brokers’ exploitation of workers like Ms Omangay.

Mr Ko thinks that the rising demand for migrant workers has led to local governments being unable to cope with the management of the workers.

He said: “The work should be better coordinated at the regional or national level, or even with a dedicated government agency established to prevent intermediaries from wielding too much authority while profiting at the same time.”

A graver issue facing migrant workers is wage arrears.

Labour ministry data released in September 2024 showed that wages owed to some 15,000 foreign workers in the first seven months of 2024 amounted to a record 70 billion won. This works out to each foreign worker being owed at least 4.6 million won.

On Nov 18, the ministry released a statement pledging “swift and strict investigations” into such complaints, while doubling down on on-site inspections where migrant workers are employed.

Earlier in June 2024, the ministry had launched a multilingual counselling service to provide support to foreign workers, such as helping them to adjust to life in South Korea and to arbitrate employment-related disputes, at 27 local labour offices across the country.

Among those seeking payment of owed wages is Ms Thlang Tepy from Cambodia, who has been waiting for the past two years to recover 29 million won from her former employer. The 28-year-old had come to South Korea four years ago to work on a farm. Although she worked more than 11 hours a day, her employer paid her for only eight hours of work and deducted up to 40 per cent of her monthly wage for living expenses.

She was housed with three other workers in a container on the farm.

When she asked her employer for a raise two years ago, she was threatened with the cancellation of her work permit, and was forced to give her employer one million won to get out of her contract. As she had left before the monthly payday, she was not paid for that month of work and did not receive her severance pay.

The 29 million won include her owed wages, severance pay and the one million won she gave her employer.

“My complaint was filed a year ago, but my former employer refuses to cooperate with the authorities and the authorities say they cannot do much,” she said through an interpreter.

She has been unemployed in the meantime and worries about her future.

“But if I leave now, I will lose all my money. I feel like I’m stuck in limbo!” said Ms Tepy, who is being assisted by two NGOs.

Like Ms Tepy, Mr Roy is also still waiting for a resolution of his case.

He had applied for industrial accident compensation from his employer two years ago but his application was rejected by the Korea Workers’ Compensation And Welfare Service, a government agency in charge of labour welfare and social security issues, which had reviewed the case based on the employer’s statement.

Mr Ajit Roy (left) has only 60 per cent of lung function left, after eight months of working at a factory grinding down metal parts with only a cotton mask for protection. His application for industrial accident compensation has been rejected and he is in the process of appealing.

ST PHOTO: WENDY TEO

Mr Roy and his pro-bono lawyer Choi Jung-kyu say that the factory had cleaned up its workplace practices for the agency’s inspection. They are appealing for a review.

“My plan was to work for just two years in South Korea and then go back to my country to become a public official. But now with my lung disease, all my hopes are dashed. My only wish now is to live longer despite my terminal disease,” said Mr Roy, who broke down while talking and needed time to compose himself.

He now takes eight pills a day and goes for a check-up every six months. Mr Roy says he cannot return to Bangladesh yet as he would not be able to receive the treatment he needs there.

“It is the only way for me to live longer, to hopefully get better and have a job again to support my family back home.”

Mr Ko, whose NGO started helping migrant workers in 2022, said: “There has been intense local media attention on the migrant workers’ plights since we started, but still nothing has changed.”

Calling for reform, he said that the foreign labour employment scheme’s “failings should be scrutinised to strengthen public interest and ensure procedural transparency and accountability”.