Turning rice into low-carbon plastic: Hope for a struggling Fukushima town

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

Mr Takemitsu Imazu, president of Biomass Resin Fukushima, showing the plastic pellets that are made from rice.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Follow topic:

NAMIE, Japan – Mr Jinichi Abe grins as he watches diggers working the earth near his rice fields, knowing they are returning more fields to productivity after Fukushima nuclear reactors exploded sprayed the area with radiation more than a decade ago.

Even better, Mr Abe knows the rice that he and a cooperative grow will have a steady buyer, and his town of Namie, still struggling to recover from the March 2011 disaster, has a new hope: a venture that turns rice unsellable for consumption due to health worries into low-carbon plastic used by major companies across Japan.

Last November, Tokyo-based company Biomass Resin opened a factory in Namie to turn locally grown rice into pellets.

The raw materials are reborn as low-carbon plastic cutlery and takeaway containers used in chain restaurants, plastic bags at post offices, and souvenirs sold at one of Japan’s largest international airports.

“Without growing rice, this town can’t recover,” said Mr Abe, 85, a 13th-generation farmer, who said the rice – unsellable because of rumours about the health problems it could cause – had been used as animal feed, among other uses, in previous years.

“Even now, we can’t sell it as Fukushima rice. So having Biomass come was a huge help. We can grow rice without worries.”

Spreading down from the forested slopes of the mountains to the ocean, parts of Namie lie only 4km from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant run by Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco), which provided jobs for many – including Mr Abe’s son and grandson.

The plant’s chimneys are clearly visible from Ukedo beach, below a primary school gutted by the March 11, 2011, tsunami.

The same wave slammed into the nuclear plant, setting off meltdowns and explosions. Namie residents first evacuated inland on March 12 that year, but then, as radiation levels rose, were ordered out of town altogether with little more than the clothes they were wearing.

Nobody was allowed back to live in Namie until 2017, after decontamination efforts left tonnes of radioactive soil stored around the town for years, including in the fields across from Mr Abe’s.

Some 80 per cent of the town’s land remains off-limits and fewer than 2,000 people live there, compared with 21,000 previously.

The town has one major shopping centre, one clinic, two dentists, one combined primary and junior high school – and a dearth of jobs. In better times, there had been a thriving pottery business, and farming, along the coastal plain.

“Fundamentally, we want businesses that will create as many jobs as possible – basically, manufacturing,” said town official Satoshi Konno, who admits things are “still tough”.

Parts of Namie town in Japan lie only about 4km from the crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Since 2017, eight companies have come in, including a concrete plant, an aquaculture business and an electric-vehicle battery recycler, generating about 200 jobs. Discussions are under way with other companies, and research institutes may bring still more people.

Biomass Resin, whose tidy factory sits on land originally set aside for another nuclear plant, is one of the newest.

“Namie was hit by four disasters – the quake, the tsunami, the reactor accident and then rumours about radiation danger,” said Mr Takemitsu Imazu, president of Biomass Resin Fukushima.

“It’s mostly recovered from the quake and tsunami, but the other two are still heavy burdens... By building our factory here, we want to bring jobs and invite people back.”

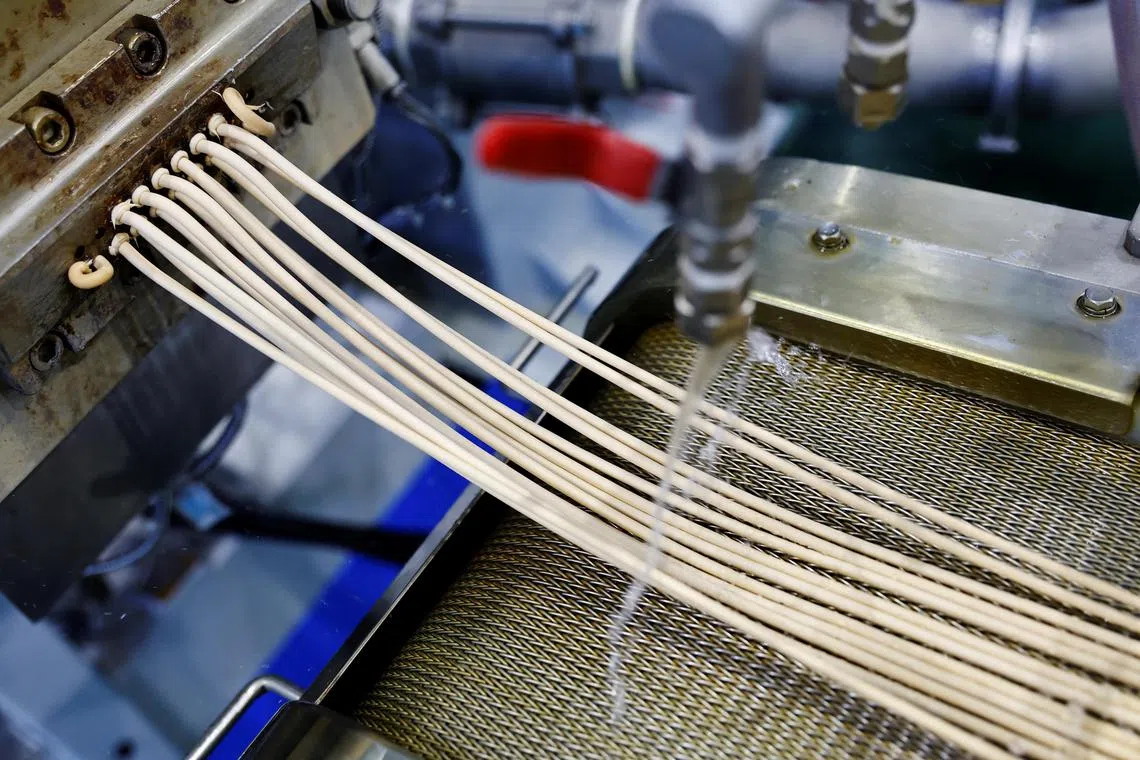

Rice combined with small plastic pellets, heated and kneaded, is extruded in long, thin rods before it is cut into tiny brown plastic pellets.

PHOTO: REUTERS

An aroma of toasted rice hangs around the factory line, where rice is combined with small plastic beads, heated and kneaded before being extruded in thin rods that are cooled and cut into tiny brown pellets.

The pellets, either 50 per cent or 70 per cent rice, are then sent to companies which manufacture plastic goods.

The plastic is not biodegradable, Mr Imazu said, but using rice cuts the petroleum products involved – and growing more rice in Namie reduces overall atmospheric carbon dioxide.

Atomic contamination experts said that rice naturally takes up little radioactive caesium. Additional testing has found no rice above strict limits, meaning the plastic is fine too.

“There’s no safety issue,” said Associate Professor Atsushi Nakao of Kyoto Prefectural University. “I really regret the rice isn’t consumed due to safety rumours, but I also understand it’s hard to completely refute aversions.”

Namie farmer Jinichi Abe in a field where contaminated soil from the fallout of the Fukushima nuclear plant disaster was stored. The land is now being converted back into a rice field.

PHOTO: REUTERS

Biomass Resin employs 10 people in Namie, including a 20-year-old who returned to live in the town, and the company hopes to expand.

It currently uses only about 50 tonnes of Namie rice; the rest of the 1,500 tonnes needed is mainly from elsewhere in Fukushima. But in 2024, it will buy more rice – grown on the freshly cleared fields – from Mr Abe and his cooperative.

Mr Abe, whose son will soon retire from Tepco and join him in growing rice, is hopeful. “This is an important thing to keep Namie going, a really good thing for the town,” he said. REUTERS