Japan to discharge treated Fukushima water into the Pacific

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

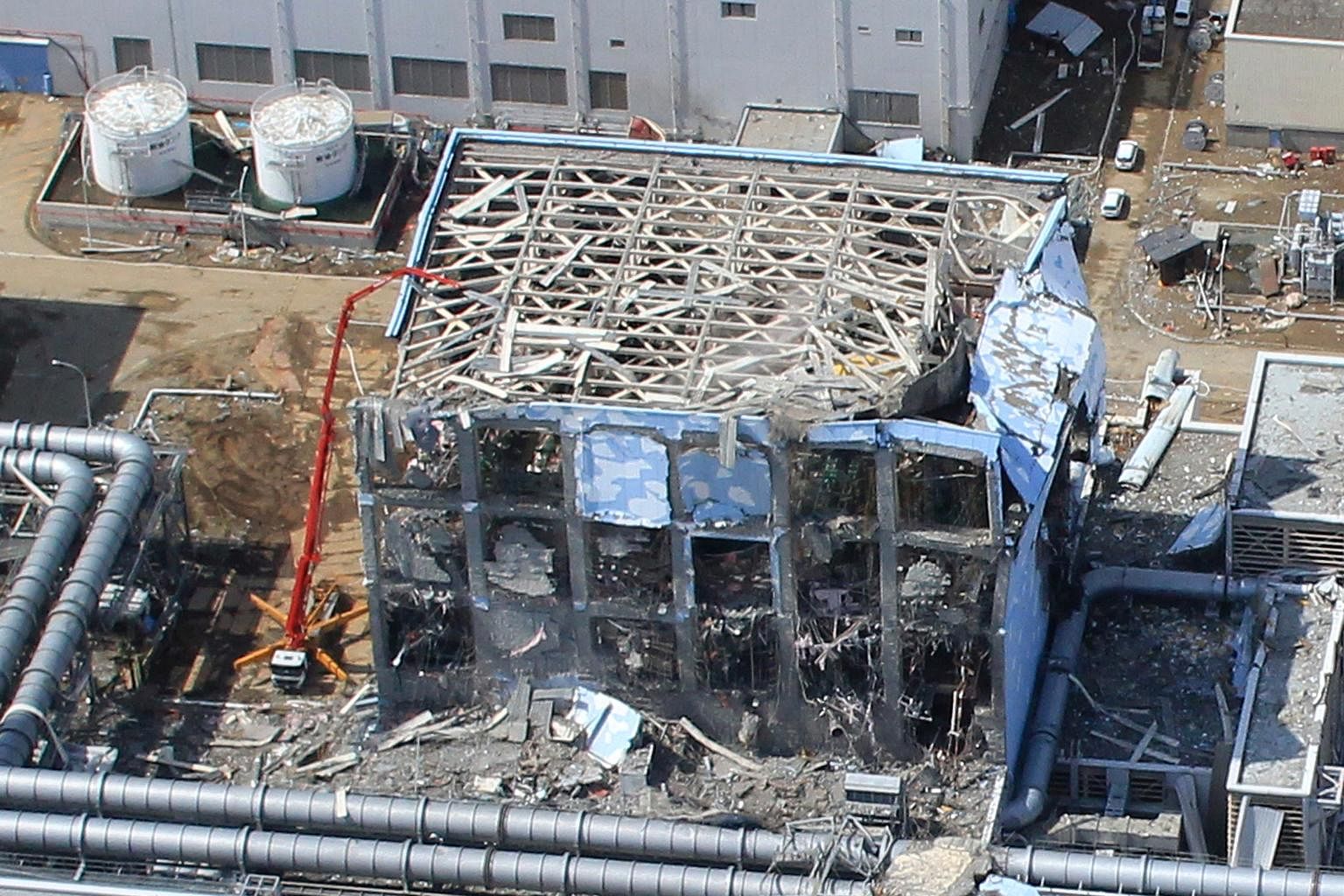

There are now more than 1,000 storage tanks, each 10m tall, at the Fukushima Daiichi complex, holding a total of about 1.25 million cubic m of water.

PHOTO: EPA-EFE

Follow topic:

TOKYO - The cooling water that has been accumulating at the crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan will be released into the Pacific Ocean after it has been treated to remove all harmful radioactive substances, Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga's Cabinet decided on Tuesday (April 13).

The discharge will begin in about two years, after the necessary preparations are complete, and take place over 30 years.

The formal decision, coming after years of agonising talks, confirms what has long been seen as a fait accompli despite the plan being a political tinderbox.

Despite the backing of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the plan has met with vehement opposition from local fishermen who fear the damage on the reputation of marine produce.

Mr Suga emphasised that this is an unavoidable matter that "cannot be put off forever", and vowed transparency in the process.

"We take it seriously that many are concerned about the damage caused by rumours and falsehoods. The entire government will work to dispel these concerns and offer sincere explanations," he said.

The United States has backed the plan, with State Department spokesman Ned Price saying: "In this unique and challenging situation, Japan has weighed the options and effects, has been transparent about its decision, and appears to have adopted an approach in accordance with globally-accepted nuclear safety standards."

But Japan's neighbours have hit out.

China's Foreign Ministry, saying that the ocean is the "common property of mankind", added: "This approach is extremely irresponsible and will seriously damage international public health and safety and the vital interests of the people of neighbouring countries."

South Korea, expressing "strong regret", called the decision a "one-sided measure made without sufficient consultation and understanding". It summoned Japan's ambassador over the decision.

But the IAEA said that Japan's plan is in line with global practice.

Before discharge, the water will be treated using the advanced liquid processing system, which can remove all radioactive material except tritium, an isotope of hydrogen that is relatively harmless even in large quantities.

Such treated water is routinely discharged into the sea as a byproduct by nuclear power plants all around the world, IAEA said.

There are more than 1,000 storage tanks, each 10m tall, at the Fukushima Daiichi complex, holding about 1.25 million cu m of water as at February. The planned capacity of 1.37 million cu m will be reached late next year.

But the water tanks are impeding the decommissioning process, and need to be torn down so the space can be used to store spent fuel and melted fuel debris that will be extracted from the damaged reactors.

The government has pledged financial aid to fishermen if their livelihoods are affected by the plan.

But Mr Kanji Tachiya, 69, a fisherman of 53 years who now heads the Soma-Futaba Fisheries' Cooperative, told The Straits Times of his fears that the decision will kill the industry, given the bad publicity.

He added that the repeated setbacks in decommissioning the plant, as well as opacity on the part of nuclear plant operator Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco), do not inspire trust.

"The most hard-nosed consumers will stick to their own beliefs even in the face of scientific evidence to the contrary," he said. "Over the last 10 years we have been trying to rebuild our livelihoods, and the decision will set us back by years."

Protestors hold slogans as they take part in a rally outside the Prime Minister's office in Tokyo against the Japanese government's decision to release treated water into the sea.

PHOTO: AFP

What is tritium

Tritium, an isotope of hydrogen, exists naturally and is found in rainwater, seawater and even the inside of the human body as a form of "tritiated water".

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) said that tritiated water poses little to no risk to human health even if one imbibes the water so long as the concentration is low, as the tritium would soon be excreted.

There is also no risk if the water comes in contact with skin.

Tritiated water is routinely discharged into the oceans by nuclear plants around the world, including in the United States, China, France and South Korea.

But Japan, wary of the fears linked to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, is taking extra steps. It has pledged to dilute the water to be released into the Pacific Ocean to 2.5 per cent of the tritium limits required under international standards for sea discharge.

This level is equivalent to one-seventh of World Health Organisation guidelines for tritium levels in safe drinking water. Drinking up to two litres of tritiated water a day is said to still be well below the amount of radiation exposure that would affect one's health.

The discharge process in Japan is expected to take three decades. But United Nations calculations show that even if the entire volume of treated water is discharged in one year, the impact would be no more than 0.1 per cent of the background natural radiation in Japan, at 2.1 millisieverts per year. This is lower than the global average of 2.4 millisieverts per year.

IAEA director-general Rafael Grossi has stressed the scientific analysis behind the decision to discharge the water, adding that it would not affect the environment.

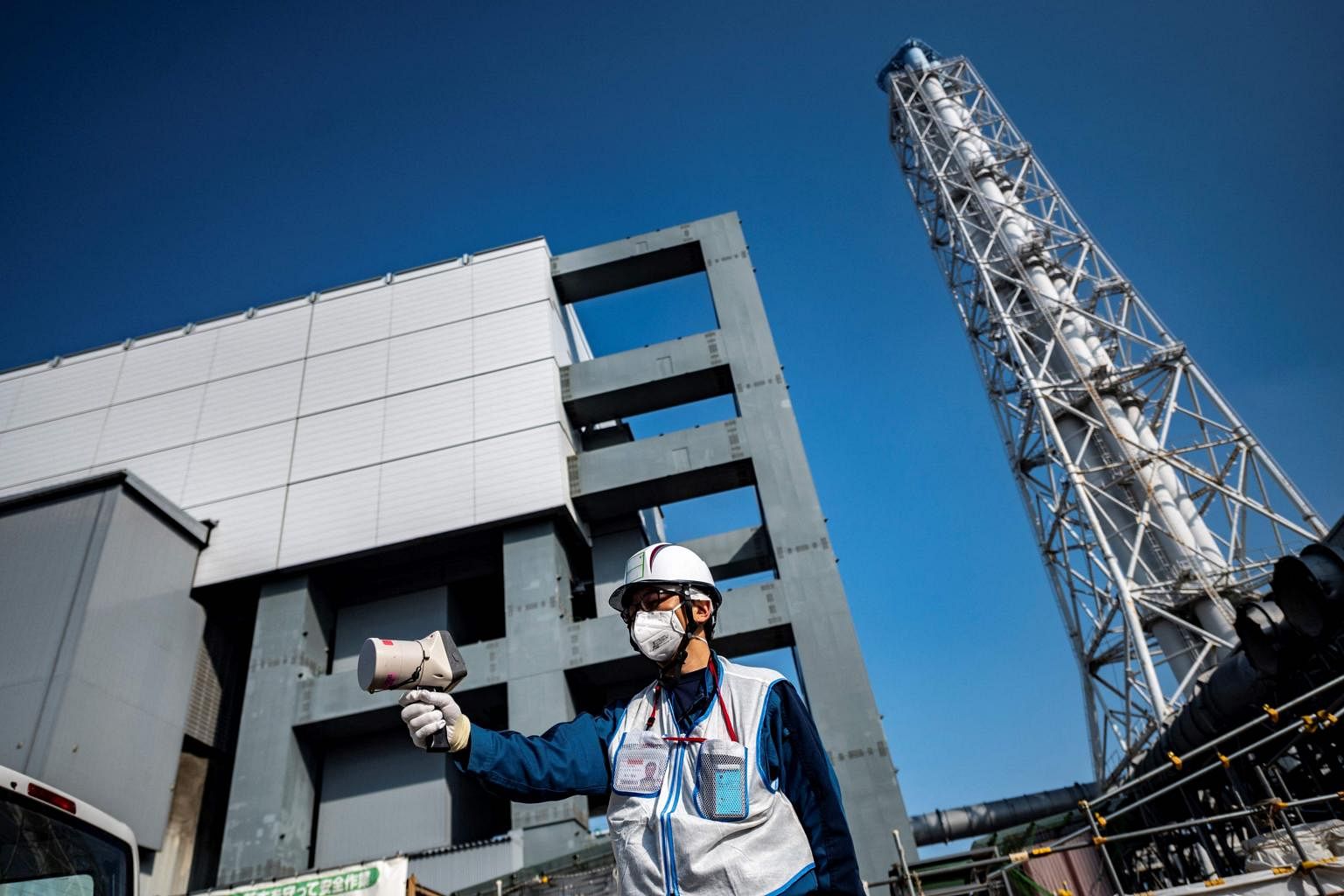

The move marks a key step in the plan to complete the decommissioning of the Fukushima Daiichi plant between 2041 and 2051.

Japan had mulled over five ways to dispose of the water:

1. By injection into deep geosphere layers 2,500m underground through a pipeline;

2. By controlled discharge into the ocean;

3. By controlled vapour release;

4. By release as hydrogen gas into the atmosphere;

5. By mixing it with a cement-based solidifying agent for burial.

Only two have been tried and tested - the disposal into the sea or evaporating the water into the air.

But the preferred option was to discharge the treated water as it would be easier to monitor its flow and subsequent impact, as opposed to how the vapour would diffuse in the air.