In South Korea, questions about cram schools, success and happiness

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

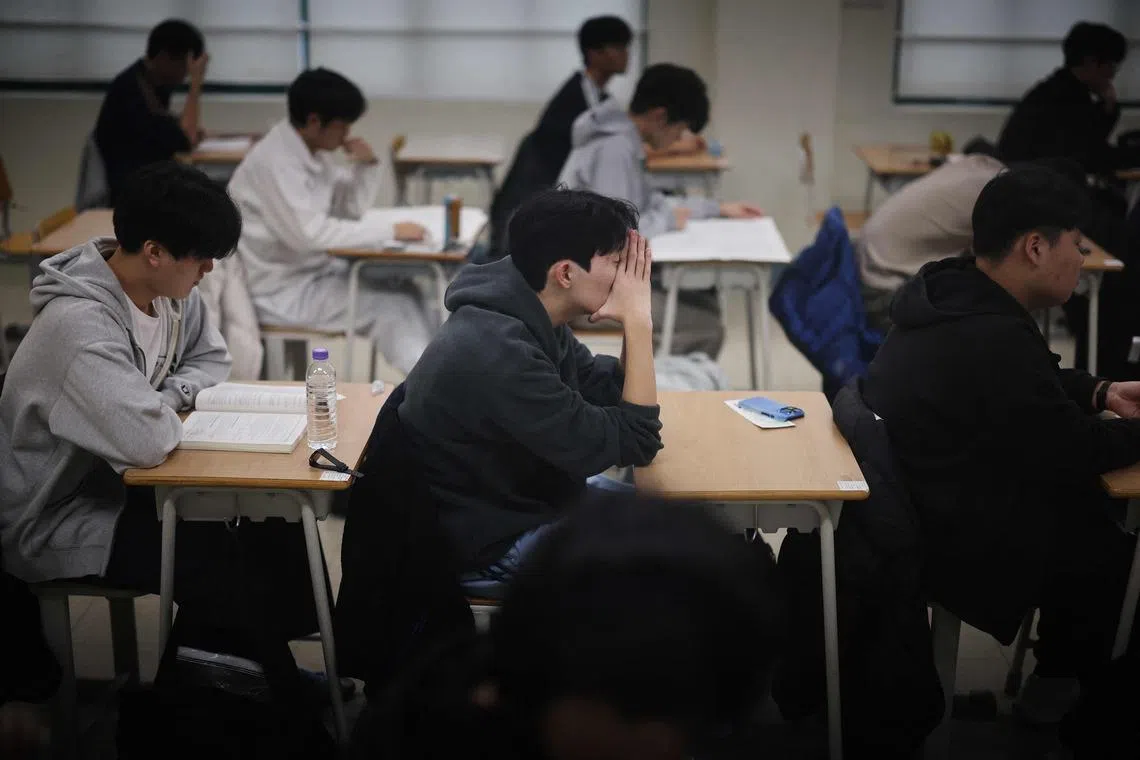

Students waiting for the start of the annual college entrance exam, known locally as Suneung, in 2025.

PHOTO: AFP

SEOUL – For years, Ms Lee Kyong-min’s life revolved around shuttling her two daughters from school to cram schools to home.

It was a routine followed by nearly every other parent she knew, all sharing the same goal: making sure their children got into South Korea’s best universities. The decisive element was their choice of hagwons, or private cram schools where students take extracurricular classes in math, Korean and English to prepare for the country’s infamously competitive college admissions exam.

Ms Lee, a former advertising professional, and her husband, who works in finance, had enrolled their children in the best they could find. Seven days a week, she waited for them late into the night at cafes packed with other parents doing the same. Sometimes, she saw little children with schedules so packed that they juggled homework and dinner in those cafes before hurrying off to their next class.

Extracurricular education, which expanded alongside the demand for university degrees as the country shifted to a white-collar economy in the 1990s, is now omnipresent in South Korea. It is also at the centre of long-running debates about the consequences of unchecked academic competition. Many parents wonder what alternatives, if any, exist.

When Ms Lee’s daughters questioned why they had to spend so much time studying outside school, she told them it was necessary because academic achievement equalled opportunity, which meant a happy life.

But her belief in this idea began to fracture when her eldest, then around 8, asked: “Mom, were you a bad student?”

“I realised she saw me as unhappy,” said Ms Lee, 46. “I felt like I’d been hit in the head.”

Now she wondered: What vision of life and happiness was she presenting to her daughters? It is a question more parents in South Korea are confronting.

Eighty per cent of South Korean school-aged students now receive some form of private extracurricular education, according to government data. While the schooling-age population has been shrinking for decades, this market grew to a record $20.3 billion in 2024.

Children are entering cram schools at younger ages. In some districts in Seoul, the capital, children as young as 4 take entrance exams for English-language preschools. Others enter medical school prep tracks in elementary school.

Even in a country long inured to intense academic competition, these developments have provoked alarm. South Korea’s human rights commission has said that subjecting preschoolers to such high-stakes testing is a violation of their rights. Lawmakers, blaming hagwons for an adolescent mental health crisis, have vowed to intervene.

But the system that created them, as Ms Lee would discover, is not so easy to change.

‘Level tests’

For Ms Lee, entering her children into the grind of hagwon education came with conflicted feelings. She and her husband both attended mid-tier universities, a fact that, in their well-credentialed world, was a source of both defiant pride and smouldering insecurity. Part of her wanted their daughters to have an enriching humanities education, and not be beholden to the college race. Another wanted them to be among its winners.

So in 2013, she enrolled her girls, then around 4 and 5 years old, in an English-language preschool. She declined to give specifics about her children, like their names, for privacy reasons.

But she said they attended numerous hagwons in Daechi, a wealthy neighbourhood in the Gangnam district of Seoul regarded as the pacesetter of educational achievement in the country. Daechi is home to 1,200 hagwons spread across an area roughly the size of Central Park.

Ms Lee grew up in Daechi and was no stranger to its reputation. Even so, she was struck by the endless loop of testing that awaited her daughters.

The most important were the “level tests”, or entrance exams held by hagwons for children as young as 4. Some, like those taken by third graders to enter Daechi’s most prestigious math hagwon, are so competitive that parents often send their children to another hagwon to study for it.

“The saying goes, if you want to send your child to medical school, you need to have them do six passes of the entire math curriculum to the high school level,” Lee said. Her eldest took the test but did not make the cut.

40 hours after school

Recently, the authorities have urged hagwons to refrain from such competitive admissions for young children.

But little has changed. Anxiety persists around the college admissions exam, the Suneung, a do-or-die test whose scope and difficulty has far exceeded standard school curriculums.

Parents are also increasingly grappling with the consequences of the system.

Ms Park Euna, a mother of three, said she got a wake-up call a few years ago, when a classmate of her eldest daughter, who was then in elementary school, died by suicide.

She recalled the classmate as a savvy and charismatic child who loved to dance but lacked a head for academics. She had been trying to get into the elite math hagwon in Daechi but had fallen short.

The episode prompted her to reconsider her children’s priorities.

“If they end up deciding they don’t want to go to college, I am fine with that,” she said.

Bad at Math

Dr Peter Na, a psychiatrist at Yale University, cautioned against drawing a straight line from pressurised academic environments to suicide, which can have complex causes.

Even so, he is troubled by the rise of depression symptoms in South Korean children under 10, as is evident in government data.

“Depression under 10 years old is not something that’s common” he said.

I don’t think it’s isolated from what’s going on in the private sector,” he said, referring to hagwons.

As Ms Lee’s daughters neared the end of middle school, her own concerns were growing because her eldest, whose gifts were in words but not numbers, was struggling.

“In the South Korean education system, if you aren’t good at math, you are seen as an idiot,” she said.

“The focus is always on what you’re bad at,” she added.

Fearful for her girls’ self-esteem, she and her husband pulled them from their multiple hagwons in 2024.

Ms Lee herself also made a career change. Now a qualified psychologist, she works as a therapist near Daechi.

A rip cord

The roots of such ratcheting competition run much deeper than merely overambitious parents.

South Korea has one of the highest rates – 76 per cent – of college enrolment in the world. But the economic insecurities that spurred this mass pursuit in the first place still persist: a weak national pension system, a shortage of high-quality blue collar jobs, limited upward mobility and yawning income disparity.

“There are no second chances in South Korea,” said Prof Byun Soo-yong, a Penn State University professor who studies the hagwon industry. “Not just where you go to college, but also the first job you get after that – all of these have huge impacts on your mobility as an adult.”

Those who can afford it have a rip cord: leaving the country. This was the path Ms Lee ultimately settled on, enrolling her daughters in a private boarding school in the United States in 2024.

She was rueful, recognising it was a privilege that few others have. “It feels like I no longer have the right to talk about the problems of this system,” she said.

Now her daughters are thriving at their new school. Her eldest is no longer seen as a slouch in math.

“Go to the US after studying math in Daechi to the eighth grade level or so,” she said, with a bittersweet laugh. “People will call you a genius.” NYTIMES