Letter From Hsinchu

Fast cars, speed dating: Lifestyles of ‘tech new rich’ in Taiwan’s Silicon Valley

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

The famed Hsinchu Science Park, which is often referred to as Taiwan’s Silicon Valley.

ST PHOTO: YIP WAI YEE

Follow topic:

HSINCHU, Taiwan – With manicured parks and rows of gleaming luxury condos, Guanxin certainly looks the part of Taiwan’s richest borough.

The average annual household income in the borough – Taiwan’s most basic level of administrative division known as li – is NT$4.61 million (S$186,000), more than three times the island’s overall average of NT$1.41 million, according to income tax data released in July.

But what may come as a surprise to some is that Guanxin is not in Taipei.

In fact, none of the island’s three richest boroughs – the other two are Datong and Zhongxing – is located in the capital city.

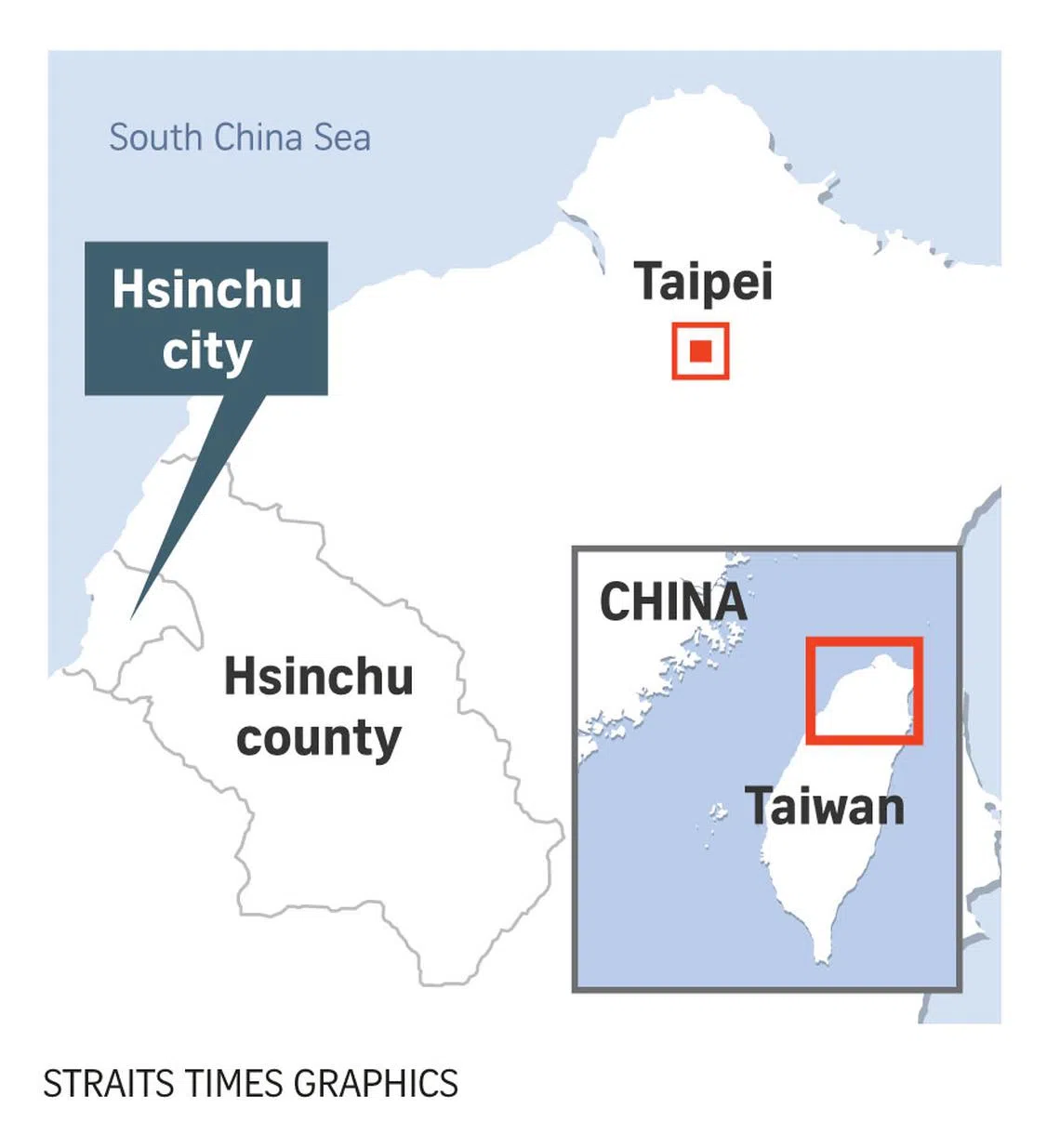

Instead, they are all in Hsinchu city or county, close to the famed Hsinchu Science Park, which is often referred to as Taiwan’s Silicon Valley.

The sprawling 1,342ha industrial park, where chipmaking giants such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), United Microelectronics Corporation and MediaTek run massive factories, has helped put the island on the world map since it opened in 1980.

Taiwan is the unrivalled leader in the production of semiconductors – the critical components found in electronic devices such as smartphones, laptops and medical equipment.

The island is estimated to supply more than 60 per cent of the world’s chips, and 90 per cent of the most advanced ones, making it a pivotal player in the global supply chain.

This lucrative sector has transformed the lives of many of the 170,000 engineers and tech professionals in the industrial park, known in Taiwan as the keji xingui, literally the “tech new rich”.

“These chip companies can afford to pay very well because their profit margins are very high as there is demand for their products – even more so now due to artificial intelligence,” said Associate Professor Shane Su from the Department of Economics at National Taiwan University.

“There is a saying that if you just work 10 years in Hsinchu Science Park, you can start thinking about retiring.”

Family-friendly

Stereotypes surrounding these tech millionaires abound.

On Taiwan television news and social media, Hsinchu’s chip engineers are typically described to be brilliant and wealthy, but also socially awkward.

More than one Taiwanese friend has told me, only half in jest, that this male-dominated workforce “only know how to talk to computers” and certainly not to the opposite sex. Only 13 per cent of engineers in all of Taiwan are women, according to a 2020 survey by the Chinese Institute of Engineers.

As a result, these male engineers in Hsinchu are often labelled as zhai nan, or nerdy homebodies who are obsessed with technology to the detriment of their social skills.

But data suggests that the stereotypes might not be true.

While Taiwan has seen its birth rate plummet to new lows every year – its 2023 total fertility rate of 0.86 is among the world’s lowest – the residential areas surrounding the science park appear to be bucking the trend.

According to a March news release from TSMC, the world’s largest contract chipmaker, children born to its employees accounted for 1.8 per cent of all the newborns in Taiwan in 2023. That means that nearly one in 50 Taiwanese newborns last year was a TSMC baby.

Hsinchu city also boasts the highest proportion of children to total number of residents.

ST PHOTO: YIP WAI YEE

Hsinchu city also boasts the highest proportion of children to total number of residents, with 13.8 per cent of the roughly 450,500 people in the city younger than 12. This is well above the island’s average of 9.96 per cent.

During my recent weekend visit to the city, it was evident that the overwhelming majority of customers in Big City, the largest mall in the area, were young families. In Guanxin borough, I spotted numerous childcare facilities and tuition centres advertising “perfect American English” lessons.

“Young Taiwanese couples want to have children, but economic concerns often stand in the way,” said National Taiwan University Professor Wang Lih-rong, a sociologist who has done extensive research on Taiwan’s fertility issues.

“But tech professionals who work in Hsinchu usually don’t have to worry about money issues, so they can purchase a home and settle down sooner,” she said, noting that buying a house is often seen as a prerequisite for marriage in Taiwan as it indicates stability in life.

Mr Jay Tsai, an engineer at leading smartphone chipset supplier MediaTek, said tech companies in the industrial park often provide comprehensive childcare services and other family-related benefits.

These companies also host regular matchmaking and speed dating events, to pave the way for its single engineers to meet employees from other departments or industries in Hsinchu, such as finance and education.

“Almost all of my neighbours in Hsinchu look like my family – where there are one or two engineer parents who have young children,” said the 41-year-old, who is married to the owner of a tutoring centre. The couple have an 11-year-old child.

The generally higher incomes of these engineers make them attractive to those seeking to move up the social ladder.

According to an August 2024 survey by popular jobs portal Yes123, the No. 1 profession that Taiwanese women hope their future husbands will be in is tech engineering, ahead of finance and medicine.

“There is the idea that Hsinchu professionals can offer a comfortable and stable way of life, and it’s true that workers at the science park earn more,” said Mr James Liao, 48, who used to be a financial manager in MediaTek.

“But this also comes at a cost – these employees work many, many hours, which means that their families might not get to spend much time with them,” said Mr Liao, who is now the chief executive of healthcare company Taichan.

Class envy?

Indeed, the notoriously gruelling hours of those who work in Hsinchu’s chip industry are a key reason why there is little class envy despite the massive income disparity between them and the rest of Taiwan’s workers.

“It is often said that these tech workers have to ‘sell their livers’,” said Prof Su, the economist, using local slang to refer to how one’s health is sacrificed due to long hours at work.

“Everyone in Taiwan knows this, so even though their pay is much higher than other people, that kind of working style is really not for everyone.”

Semiconductor engineers are expected to be on call 24 hours a day – a high level of productivity and efficiency that experts say contribute to Taiwan’s peerless success in the field.

While the median annual income of those working in the infocommunications sector in Hsinchu city reached NT$1.29 million in 2022, Taiwan’s overall median annual income was only NT$518,000, or about NT$43,170 a month.

Salaries have also stagnated for years for most workers outside of the chip sector, with real wages growing by an annual average of just around 1 per cent over the past decade.

In May, Taiwanese officials said that increasing wage differences across sectors have led to wealth inequality, with the island’s household wealth gap

In 2021, the richest 20 per cent of households held 66.9 times more wealth than those in the bottom 20 per cent.

Mr Tsai, who began working at MediaTek in 2008, acknowledged that he was likely in the 90th percentile even as a junior engineer then with a starting annual salary of around NT$2 million. But he would clock at least 12 hours on any given work day, sometimes for six days a week.

“It’s tough work, the mental stress can be overwhelming. But I think it’s worth it because I can take care of my family,” he said.

As a manager, he now has a more flexible schedule and can afford to take his family overseas on holidays three times a year.

With fuller pockets, Hsinchu’s tech professionals can also indulge in more luxury goods, such as fast cars.

In March, the Financial Times reported that Ferrari sales in Taiwan doubled over the past four years, fuelled by the growing wealth of the island’s chip entrepreneurs.

Over at Porsche Centre Hsinchu, head of sales and marketing Ronny Liu declined to provide specific sales figures, but noted one unique quality among the city’s shoppers.

Mr Ronny Liu at Porsche Centre Hsinchu.

ST PHOTO: YIP WAI YEE

“Unlike those from old money, these tech workers are not looking only for the brand name. They want to know what kind of fancy high-tech options you can provide them – and who knows, they might have had a hand in developing these functions too,” he told me, chuckling.

Mr Liao, the former Hsinchu Science Park worker, said that ultimately, the city’s “tech new rich” are “highly rational”.

“Hsinchu is a ‘work city’. Everything revolves around work, so you want to use your money to pay for a nice house near work and a nice car that takes you to work,” he said.

Despite the draw of high salaries, he does not believe that money is the sole motivating factor for why many choose to remain employed in the punishing chip sector.

Pointing to the skyscrapers and high-speed rail station behind him, he noted that none of them had existed just 20 years ago.

“These were all just rice paddies. No one would have believed that Taiwan could become a world-leading chip producer, but now these chips are in all of our devices,” he said.

“I believe these tech workers stay because of that personal sense of achievement.”