Big dreams, shiny projects and regional inequalities in China’s inland cities

Large metropolitan areas in central and western China are powering ahead, but will the benefits of their growth spill over?

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

The Chongqingdong high-speed rail station, with six funnel-shaped pillars at its entrance resembling the municipality’s signature white fig trees and their wide-spreading canopies, is the latest symbol of Chongqing’s development.

PHOTO: NI QIANSONG

CHONGQING – Robotaxis that ply the streets of Wuhan are equipped with heated seats and massage functions. Rides are ordered via an app, and commuters confirm their identities on the touchscreen windows of the driverless cabs before they are whisked off.

In 2019, the capital of Hubei province became the first Chinese city to issue commercial licences for trials of driverless vehicles in open road conditions.

Today, it is a global front runner in driverless technology, a key area in the country’s fractious competition with the US that Chinese leaders are keen to dominate.

While the coastal cities of Shanghai, Zhuhai and Xiamen have long been China’s economic powerhouses, inland cities – that had lagged behind for years because of their more remote locations – are showing why it is now their time.

They are seeing the fruit of policies to reduce regional inequalities, such as the Go West strategy in 2000 and the Rise of Central China plan in 2006, which focused on industrialisation and connectivity in those regions.

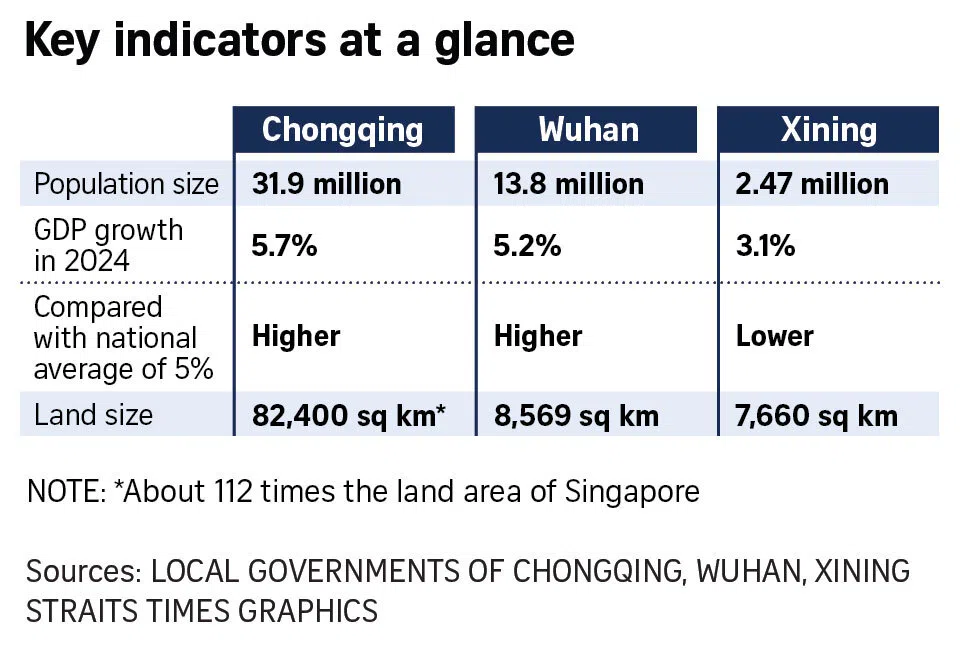

Central provinces Hubei and Anhui as well as western Gansu grew 5.8 per cent in 2024, beating the national average of 5 per cent that year.

Today, gleaming skyscrapers and flagship infrastructure projects dot the landscape in cities in these provinces.

The provincial-level municipality of Chongqing has also overtaken Guangzhou, the capital of southern Guangdong province, to become China’s fourth-largest economy in 2022, during the 14th five-year plan period.

Chengdu, Hefei and Zhengzhou, like Wuhan, are also technological powerhouses in their own right.

Driverless vehicles in Wuhan’s national intelligent connected vehicle zone.

PHOTO: WUHAN ECONOMIC AND TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT ZONE

Booming inland cities have also been tasked by the central government to drive growth in their neck of the woods, as per national development plans.

China’s push for “common prosperity” – an aspiration pledged by the late leader Deng Xiaoping – will be a key theme in the upcoming five-year plan,

The new plan marks the midpoint in China’s goal to be a “moderately prosperous” country by 2035, with a more balanced distribution of wealth.

Beijing said in July that improved coordination between the country’s different areas over the past five years has allowed “all regions and people to share the fruits of development”.

This has been key, as “China is vast, with different conditions in the east, west, north, south and centre”, said Mr Zheng Shanjie, chairman of the National Development and Reform Commission, the country’s top economic planner.

“We have objectively recognised regional gaps, (and) regions have found their roles within the overall development of the country,” he added. He said success has come from integrating the industrial, technological, managerial and financial advantages of the east with the resource endowments of the west.

Several inland hubs have, during the 14th five-year plan, strengthened or developed their own niches, including technological innovation, logistics and green tech.

To overcome the remoteness and difficult terrain of these inland areas, the central government has earmarked funds and resources for connectivity projects. China now has the world’s most extensive high-speed rail network and busiest ports such as those in Wuhan, Xi’an, the capital of western Shaanxi province, and Chongqing.

China now has the world’s most extensive high-speed rail network and busiest ports such as those in Chongqing (above), Wuhan and Xi’an, the capital of western Shaanxi province.

PHOTO: ST FILE

Richer cities and provinces have been paired with poorer regions, helping them grow by buying their local products and partnering with their firms as well as transferring expertise such as e-commerce skills, as part of a national initiative known as East-West Collaboration that started in the 1990s.

Before 2021 – the year China declared the end of extreme poverty in the country – the initiative was known as the East-West Poverty Alleviation Collaboration, with pairings between Shanghai and Yunnan, Fujian and Ningxia as well as Guangdong and Guangxi.

Analysts expect the new 15th five-year plan to further lift promising cities as top policymakers double down on boosting China’s technological prowess and domestic consumption. But they also warned about inequality worsening within the inland regions as high-performing cities surge ahead.

For example, some inland cities like the capitals of Qinghai, Guizhou and Shaanxi have lagged, hamstrung by their remoteness and lack of manpower and industries, among other factors.

Asian Insider takes a closer look at the development trajectory of three inland cities: Wuhan and Chongqing, which have pulled ahead of the pack thanks to their specialisations in technology and logistics respectively, and Xining, whose remoteness and lack of skilled talent stymie its green tech ambitions.

Wuhan: Banking on science and technology

While Wuhan is considered a global leader in intelligent vehicle transportation, with one of the world’s largest robotaxi fleets, the city is not resting on its laurels.

In 2025, it became the first city in China to enact laws that ensure the regulated growth of intelligent connected vehicles (ICV), providing much-needed policy clarity to carmakers.

ICVs are automobiles equipped with advanced technology, allowing real-time communication with other vehicles on the road, roadside infrastructure and cloud-based systems. China – the world’s largest car exporter – has named ICVs as one of its priority areas to grow its economy.

The wide-ranging new laws kicked in on March 1 and covered issues such as industrial innovation and accident liability.

Chief economist Hong Wensheng from the Wuhan Development and Reform Committee, the city’s economic planner, told The Straits Times that Wuhan rose to become one of China’s leading tech hubs on the back of strong policy support that built on the city’s existing strengths in technology and manufacturing.

For example, Beijing granted Wuhan the central region’s first national-level ICV testing and demonstration zone in 2019 because of the city’s strong automobile sector, he noted.

President Xi Jinping had during his official trips to Hubei, most recently in 2022 and 2024, given the province the responsibility of using science and technology to drive economic growth as a development strategy for central China.

Central authorities in April 2022 approved a master plan to “turn Wuhan into an influential domestic sci-tech innovation centre”.

Wuhan was long one of China’s automotive hubs.

PHOTO: WUHAN ECONOMIC AND TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT ZONE

Wuhan, briefly China’s wartime capital under the Kuomintang government during the Second Sino-Japanese War, was long one of China’s automotive hubs.

The city later gained further prominence as a tech hub after China’s first optic fibre was produced by a research lab in Wuhan in 1979. It led to the establishment of one of China’s foremost high-tech industrial parks – the East Lake High Tech Development Zone – in 1988.

Also known as Optics Valley, the East Lake park contributed 15.2 per cent to the city’s overall gross domestic product (GDP) growth in 2024, up from 13.6 per cent in 2023. Besides the optoelectronics industry, medical and renewable energy firms as well as high-end equipment manufacturers are also housed in the park.

China's first commercial suspended monorail line in operation in Wuhan's Optics Valley. Besides the optoelectronics industry, medical and renewable energy firms as well as high-end equipment manufacturers are housed in the park.

ST PHOTO: AW CHENG WEI

With Wuhan leading the charge, Hubei was one of China’s fastest-growing provinces in 2024, recording a GDP expansion rate of 5.8 per cent, higher than the national average of 5 per cent.

In the first six months of 2025, Hubei grew 6.2 per cent, surpassing the national average of 5.3 per cent. The population in Wuhan grew to 13.8 million in 2024, up from 10.6 million in 2015.

In May, Hubei vice-governor Cheng Yongwen told the media that the province’s greatest strengths are in “science, education and talent”.

Hubei has 133 universities with 2.15 million college students, one of the highest figures in the country. It also has about 45 national laboratories that work on scientific breakthroughs and applied research in areas such as aerospace, automotive and biomedicine.

Hubei has 133 universities with 2.15 million college students, one of the highest figures in China.

PHOTO: AFP

Wuhan’s roll-out of the new laws for driverless technologies marks the next step in the city’s push to stay ahead in the global tech race, Mr Wu Haiping, director at the Intelligent Connected Vehicle and Smart City Division at the Wuhan Economic and Technological Development Zone, told ST.

“We worked with the automobile industry as well as the city’s builders to come up with the laws so that the regulations are comprehensive and represent a diversity of views,” Mr Wu said.

For instance, smart street lamps, which can transmit data through high-speed networks, were developed together with the self-driving vehicles in the demonstration zones, Mr Wu said.

The fixed locations of street lamps can serve as reference points for high-precision positioning in autonomous driving technology, ensuring traffic safety.

But the push for driverless technology has not been all smooth sailing, and has come under the microscope after some accidents. three people died after a Xiaomi smart car hit a concrete barrier while in semi-autonomous mode.

For example, in a high-profile case in April in central Anhui province,

Mr Wu said: “We hope to continue leading the country’s development in driverless technologies by conducting more tests in different scenarios to ensure safety for passengers, drivers and pedestrians.”

Chongqing: ‘Comprehensive transportation hub’

In some western and central provinces, the disposable income for each person has also closed on, or even surpassed, the national average.

The average monthly disposable income in Chongqing – which is China’s largest city in terms of land size and population – hit 22,117 yuan (S$4,000) per capita for the first half of 2025, an increase of 5.1 per cent from the same period in 2024.

This is higher than the national average of 21,840 yuan. Full-year averages in Chongqing, however, have trailed behind the national figure for at least the past 10 years.

Situated along the Yangtze River and one of its main tributaries, Chongqing is the meeting point for Mr Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative, and the Yangtze River Economic Belt, which encompasses 11 provinces and accounts for about half of China’s population and economic output.

Together with Chengdu, the capital of neighbouring Sichuan province, Chongqing drives growth in the south-west and western regions, under China’s Go West strategy.

It also provides the key transportation links for the region.

The world’s largest high-speed rail station, Chongqingdong, opened its doors in June. A landmark in the historic Nan’an District in south-west Chongqing, the new station is flanked by some of the country’s most modern tracks, facilitating the movement of train carriages up to speeds of 350kmh.

The world’s largest high-speed rail station – Chongqingdong – that opened its doors in June is roughly the size of 170 football fields. The eight-storey station is the latest symbol of Chongqing’s development.

PHOTO: NI QIANSONG

The authorities said the new hub, roughly the size of 170 football fields, will eventually help to shorten travelling times to major cities such as Beijing and Shanghai. Currently, the fastest trains from Chongqing take about seven hours to reach Beijing and about nine hours to Shanghai. Chongqingdong, which can accommodate 10,000 passengers and visitors every hour, will shorten those times to about six hours.

The eight-storey station with six funnel-shaped pillars at its entrance resembling the municipality’s signature white fig trees and their wide-spreading canopies, is the latest symbol of Chongqing’s development. Mr Xi has labelled the city a “comprehensive transportation hub for the opening of inland cities”.

During an official visit in April 2024, he said Chongqing was to be a “strategic fulcrum of the opening up of western China” – one of the country’s poorest areas that include neighbouring Guizhou and Yunnan provinces as well as the Xinjiang autonomous region.

Chongqing, he said, should “play a bigger role in constructing a modern logistics system” that can drive the opening up of western and inland regions.

Results have been promising so far. Official data showed that from January to May in 2025, Chongqing’s imports and exports through the Western Land-Sea Corridor grew 1.8 times from a year ago, with cargo value hitting 22.26 billion yuan, a 15 per cent hike from the same period in 2024.

The Western Land-Sea Corridor, which is part of Mr Xi’s signature Belt and Road Initiative, runs through 18 provinces and 73 cities in China and connects to 560 ports in 127 countries and regions.

Trucks loading shipping containers at the Chongqing International Logistics Hub Park. From January to May in 2025, Chongqing’s imports and exports through the Western Land-Sea Corridor grew 1.8 times from a year ago.

PHOTO: EPA

Chongqing’s economy, one of the fastest growing in China, expanded 5.7 per cent in 2024, 0.7 percentage point higher than the national average of 5 per cent, due to strong exports and manufacturing.

In 2025, officials are aiming to hit a 6 per cent growth target. For the first half of the year, Chongqing grew 5 per cent, slightly below the national average of 5.3 per cent.

Chongqing’s air connectivity is also being bolstered.

In June, transport officials announced that the number of entry and exit points at the municipality’s international airport will be increased to 13, up from the current seven, allowing for more flights.

It has also expanded automobile production – a key driver of its economy – with the goal of contributing 10 per cent to China’s car exports by 2027.

Chongqing was China’s capital during World War II and turned a number of its former military factories to production lines for automobiles, which have provided a strong base for its ambitions. Officials have set the goal of producing 36.4 per cent more electric cars in 2025, or a total of 1.3 million units, from 2024.

Changan Automobile, one of China's biggest carmakers, produces some of its cars in Chongqing. The municipality has expanded automobile production, with the goal of contributing 10 per cent to China’s car exports by 2027.

ST PHOTO: AW CHENG WEI

Director Ding Yao at Chongqing Comprehensive Economy Academy, a government think-tank, told ST that the municipality’s advantages in building and selling cars lie in its strong production lines, which count some of China’s biggest carmakers such as Changan Automobile and Ceres.

But Chongqing’s push to develop its automobile industry is not without its challenges, she said.

Chongqing continues to rely on imports for automotive chips and high-precision sensors, among other key accessories, she added, estimating the municipality’s automotive chain to be about only 45 per cent complete. Mainland China’s smart car industry relies heavily on chips from Europe, the US and Taiwan.

“There’s also a lack of suitable talent in the ICV industry, particularly those who can promote Chongqing cars to overseas markets, and a disconnect between universities’ scientific research with industry demands,” she said.

Xining: Green push amid slowing economy

The capital of Qinghai, China’s largest landlocked province, is 2,261m above sea level on the Tibetan Plateau, the world’s highest and largest plateau.

Xining’s altitude is a key reason that it struggles to attract new residents or talent, which has affected its overall development, locals said.

“Not many out-of-towners like it here because some get headaches and even feel nauseated or short of breath. They also find Xining boring,” said eatery owner Chen Mohui, 39.

Tibetan flags arranged in the shape of a tent against a background of rapeseed flower fields at the foot of Riyue Mountain in Qinghai. Qinghai lies in the north-eastern part of the Tibetan Plateau in China.

ST PHOTO: AW CHENG WEI

This is even though it is the largest city in a former mining province with natural assets that should smooth its pivot towards high-tech and green tech industries.

Xining is a draw for resource-hungry data centres, intelligent computing hubs and super-computing centres, given that more than 80 per cent of its electricity grid is powered by green energy, local media Xining Evening Daily said in a report on July 31.

Its higher altitude also means cooler temperatures, translating to lower costs for companies to keep their engines and batteries running even during summers, the report added. China Mobile and China Telecom, two of the country’s largest telcos, have data centres in Qinghai.

Qinghai also houses a couple of the world’s largest solar farms – the Golmud CPV Solar Park and the Talatan Solar PV Park – and accounts for 29 per cent of national wind power capacity.

A satellite image showing fields of solar panels in the Talatan Solar PV Park in China’s Qinghai province.

PHOTO: AFP

But for locals, the green push has not meant better job opportunities, given their lack of skills and training for these industries. And with outsiders reluctant to brave the harsh climate, Qinghai, which neighbours the Tibet autonomous region, has found itself falling behind.

It is China’s second-slowest growing province, recording a GDP growth of 2.7 per cent, far lower than the national average of 5 per cent, in 2024.

Only northern China’s Shanxi is further behind, with an expansion rate of 2.3 per cent for 2024. In the first six months of 2025, Qinghai grew 4 per cent year on year, 1.3 percentage points below the national average.

The former mining provinces, which also include Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning provinces in China’s north-eastern rust belt region, floundered after tighter laws on polluting sectors were passed to better protect the environment.

China is the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, though it has committed to reach carbon neutrality by 2060.

These provinces did not move with the rest of the country towards light manufacturing industries such as clothing and other consumer goods and technological innovation.

Qinghai is the source of the Yangtze, Yellow and Mekong rivers, and the province is known for its mineral resources, particularly copper, lead, zinc, nickel and coal.

Qinghai province is named after Qinghai Lake, the largest saltwater lake in China and a major tourist attraction.

ST PHOTO: AW CHENG WEI

Local and online media outlets have reported that in 2023, Qinghai’s zinc, lead and copper accounted for between 55 and 65 per cent of China’s proven reserves. But with the pivot towards green tech, these mining sectors have become less relevant.

Furthermore, China’s toughened its regulations in 2015 to beef up penalties for unlicensed mining and failure to comply with environmental laws, including punishments such as cumulative daily penalties, criminal liability and detention, making it difficult for mining companies to continue operations.

These days, mining in Qinghai is focused on lithium, a key ingredient in rechargeable batteries, as China aims to grow its technological and renewable energy industries.

An estimated 40 per cent of China’s total mined lithium comes from Qinghai, according to industry reports, making the province one of the country’s top producers for the key natural resource.

Mr Xi said during an inspection tour of Qinghai in June 2024 that Qinghai needs to “adhere to the principle of prioritising ecological protection and pursuing green development”. In 2023, China passed a Qinghai-Tibet Plateau ecological conservation law that came into effect later that year.

But Qinghai needs to overcome some steep challenges.

When China finally abolished its zero-Covid policy in late 2022 and lifted travel restrictions within the country, the resident population of Xining began dipping, in a sign that even the locals are leaving.

Official statistics showed that at the end of 2024, Xining had about 2.47 million residents, down 0.17 per cent from the year before. It also came on the heels of a 0.18 per cent drop from end-2022.

Xining is a draw for resource-hungry data centres, intelligent computing hubs and super-computing centres, given that more than 80 per cent of its electricity grid is powered by green energy.

ST PHOTO: AW CHENG WEI

A taxi driver who gave his name only as Mr Yang said that his daughter left Xining in 2023 for Xi’an, the capital of Shaanxi province, after she was laid off from her sales job in 2021.

Mr Yang, 54, said: “I saw how hard my daughter looked for a job, and while she had some offers, the salary was not great.”

Mr Yang and Mr Chen, the eatery owner, told ST that many residents in Qinghai lost their jobs during the decline of the province’s mining industry in the late 2010s.

Mr Chen said: “The decline in the mining industry, like the current downturn in the property sector, affected many jobs in heavy manufacturing, which had also bloomed in Qinghai due to the proximity to the mines.”

Ms Shan Guo, a partner at Hutong Research consultancy in Shanghai, expects Qinghai as well as other provinces rich in energy resources such as Shanxi and those in north-eastern China to eventually become energy farms for the rest of the country.

“More will leave these (provinces) and move into bigger metropolitan areas for different job opportunities,” Ms Guo said.

Xiguan Street in Xining is one of its more popular areas, with a number of malls, eateries and residences.

ST PHOTO: AW CHENG WEI

Mr Yang said the most sought-after jobs in Xining now are with state-owned enterprises or the government service, which offer fixed hours and manageable workloads.

Civil servants who move to Xining or Qinghai from elsewhere are eligible for many subsidies due to Qinghai’s high altitude.

“Many government employees may work here for a few years to show that they can ‘endure hardship’ given that the living conditions in Qinghai are not great before they go on to another city, usually for a better posting,” Mr Yang said.

Can China go further to narrow regional inequalities?

With the growth engines identified for each region, analysts expect the authorities to focus their efforts on further boosting metropolitan clusters.

The national dushiquan strategy, rolled out in 2021, hinges on key cities that have the best chance of driving growth in their surrounding areas. Nanjing, the capital of eastern Jiangsu province, was named the country’s first dushiquan in March 2021.

Currently, China has 17 dushiquan, or metropolitan clusters, spread across the country, with Shijiazhuang, the capital of northern Hebei province, being the latest addition. There are about five dushiquan in central and western China.

Ms Guo said: “These dushiquan will create jobs and other opportunities that will draw more Chinese to live in them or around them as growth ripples out in the area.”

Ms Guo envisions key cities in China’s central and western regions becoming a “strategic hinterland” for the country, given their focus on logistics and industrialisation in the country’s plans for them.

She predicts that China’s “innovation and consumption are likely to be focused in the east”, including Shanghai, given the higher spending power and talent of the residents there, while labour-intensive industries will increasingly shift westwards.

Ms Guo said that China’s move towards the dushiquan strategy marks a change from the country’s previous development strategy, which aimed at keeping residents in their home towns through the hukou or household system.

China introduced the hukou system in 1958 to prevent its key cities from being flooded with domestic migrants by limiting residents’ access to medical, housing and education resources to their home towns.

But Mr Deng’s opening-up policy in 1978 resulted in millions of Chinese uprooting and moving around the country, particularly to eastern and southern coastal areas, for better jobs, even if they had to cope with a lack of access to public services. This widened regional inequalities.

While the disparities have since narrowed as the Go West strategy was rolled out, analysts expect policymakers to increase efforts to tackle this issue in the next five-year plan.

They pointed to how the term “common prosperity” – a goal of China that dates back to Mao Zedong’s rule – is now about bridging the wealth gap. Mr Xi raised the topic of common prosperity in his articles and speeches in 2021, and a government White Paper that year stated that “income disparities and the gap in development between urban and rural areas and between regions remain a severe problem”.

But professor of economics Albert Hu at the China Europe International Business School in Shanghai warned that China’s ambitions are contending with slowing economic growth and weak domestic demand.

Weak domestic demand continues to plague China’s economy, despite policymakers’ efforts to drive consumption with a plethora of measures such as spending vouchers, subsidised trade-in programmes for electronics and discount coupons.

Prof Hu said: “Ultimately, domestic demand will need to rely on income growth, which has been stagnant or slowing in China, as overall momentum slows.”

Mr Yang, the taxi driver in Qinghai, is not optimistic that conditions in Xining will improve, given the nation’s economic slowdown.

This also means that his daughter is unlikely to return from Xi’an in the near future, or settle down near him and his wife.

“As a parent, I really hope that I can live in the same city as my child, but I understand that she is also working hard to support herself and give herself a brighter future,” Mr Yang said, adding that he and his wife still hoped for “a grandchild or two”.