Letter From Hong Kong

A globalised Hong Kong is making Cantonese more accessible to the world

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

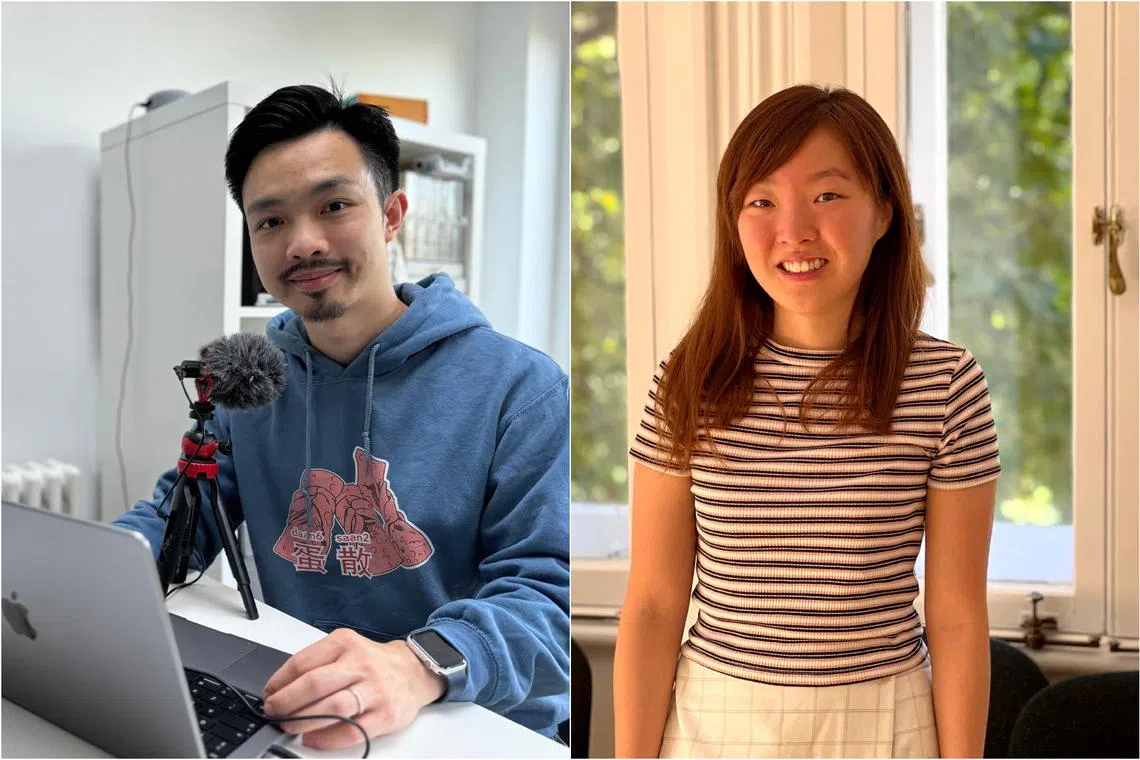

Mr Jeffrey Wong and Ms Ceci Pang are among many globalised and tech-savvy Hong Kongers who are making Cantonese more accessible to the world.

PHOTOS: COURTESY OF JEFFREY WONG, MAGDALENE FUNG

Follow topic:

HONG KONG – Hong Konger Jeffrey Wong started his Instagram account Jyuttoi in 2022, sharing interesting Cantonese idioms to help people pick up the language through casual conversation.

Two years on, he has more than 111,000 followers, among them Hollywood stars like US-born actor Daniel Wu, whose parents hailed from Shanghai; British actor Benedict Wong, whose parents emigrated from Hong Kong; and even Singapore’s Minister for National Development Desmond Lee.

Mr Jeffrey Wong is a Hong Kong-born-and-bred software engineer in his 30s who moved to England in 2021. In his free time, he produces his online content and collaborates with non-profit organisations in places like the British capital of London and Calgary city in Canada on creative ways to keep Hong Kong’s language alive as more of its residents emigrate.

He is among many globalised and tech-savvy Hong Kongers who are making Cantonese more accessible to the world, tailoring their content and programmes largely to foreign language learners, including British-born ethnic Chinese of Hong Kong descent.

“Cantonese has always been a very big part of my life. But when I moved to Britain, suddenly it started playing a significantly smaller role, and I wasn’t ready for that,” said Mr Wong, who majored in translation and Spanish at the University of Hong Kong.

“I was surprised to find out that although Cantonese is among the top 30 most spoken languages in the world – even more than other Asian languages like Korean or Thai – the materials available for people to pick up Cantonese are actually very scarce. So I thought I could start teaching some informal lessons online,” he told The Straits Times in a video call.

Cantonese ranked No. 20 among the world’s most spoken languages in 2023, according to global language database Ethnologue.

Cantonese is identified as a language – as opposed to a dialect, which is a variant of a language, like the French dialect Quebecois – because it cannot be understood by another party who has not learnt it and of the existence of a distinct literature and ethnolinguistic identity among its speakers.

The language, which dates back to around the ninth century, is now spoken by more than 85 million people worldwide, mostly in southern China where Guangdong province, Hong Kong and Macau, with a combined population of 135 million, are situated.

Mr Wong’s Instagram content comprises illustrated flashcards introducing often humorous idiomatic Cantonese phrases along with their English translation, traditional Chinese characters, Jyutping pronunciation, and sound clips of how the phrase is spoken and used in an everyday context. Cantonese can be written in the traditional Chinese script.

Jyutping is a standardised romanisation scheme for Cantonese, similar to pinyin for Mandarin.

Mr Wong has also created videos, some of which teach colourful descriptive adjectives in Cantonese or explain the range of meanings for Cantonese speech particles used in different contexts, not unlike those in Singlish like “orh…”, “har?”, “wah!” and “cheh”.

While most of the idioms he teaches are widely used in Hong Kong, he admits that some of the phrases he introduces are “somewhat old-school, or archaic”, such as “ngai do lau sei zoeng” – literally “many ants can kill an elephant”, meaning that when united, even weak powers can overcome a great force.

But learning these phrases has helped some of his heritage-speaker followers born abroad bond better with their Cantonese-speaking parents and grandparents, he said.

Mr Wong is surprised at the popularity his account has gained in just two years.

He receives collaboration requests from time to time to celebrate or raise awareness of the Cantonese language and culture among Hong Kong migrants in foreign countries.

Over Chinese New Year, for example, he held a workshop for an insurance firm in central London, teaching participants how to play Hong Kong mahjong.

“I named my Instagram account Jyuttoi – a play on words that essentially mean ‘a Cantonese platform’ – because I hope for it to be a place that brings people together as they embark on their journey to learn Cantonese,” Mr Wong said.

Mr Jeffrey Wong giving a mahjong workshop in London.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF JEFFREY WONG

HK teachers in Britain

Not far from him, in central London, Ms Ceci Pang has been running Rainbow Seeds Cantonese, which provides Cantonese-based education to children and adults, for seven years.

Ms Pang, a former Hong Kong kindergarten teacher in her 20s, set up the playgroup – which runs like a tuition centre – a year after relocating to Britain.

She started out by giving one-on-one private lessons in Cantonese to children of Hong Kong descent.

As her classes gained popularity through word of mouth, she expanded it to include group lessons, hired other teachers, sourced for affordable room rentals within public facilities like libraries, designed full-fledged curricula for her students, and set up a school website and multiple social media accounts.

“Initially when I left Hong Kong hoping for better work-life balance in London, I wanted only to teach,” Ms Pang told ST in a video interview.

“But my experiences here have broadened my horizons, and I find myself now aspiring to contribute more fully to my students’ development, teaching them – through the Cantonese language – to solve problems and expand their skill sets,” she said.

The playgroup – which runs private classes on weekdays and group lessons on weekends – has an enrolment of students numbering “in the low hundreds”, almost all third-generation British-born Chinese (BBC) children, and some adults seeking to reconnect with their heritage.

Ms Ceci Pang engaging children in a lesson at Rainbow Seeds Cantonese in London.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF CECI PANG

Once in a while, the classes offered also attract learners of other ethnicities simply interested in picking up Cantonese as a foreign language, Ms Pang said.

Recent years have seen an influx of new Hong Kong immigrants after Britain offered them a route to citizenship following Beijing’s imposition of a national security law in the territory in 2020.

This influx has widened the pool and raised the quality of Cantonese-language teachers that her school can tap, she said.

But she has also observed a difference in attitudes towards the Cantonese language among British-born people of Hong Kong descent and that of the new Hong Kong immigrants.

“Compared with second- or third-generation BBCs, the newcomers tend not to prioritise keeping Cantonese language use alive in their family,” Ms Pang said.

“They are often too occupied with trying to settle down and help their children fit into their new, English-speaking environment.”

Ms Ceci Pang (centre) with her students using self-designed textbook materials.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF CECI PANG

Ms Pang would like to see these new immigrants persist in using their mother tongue at home.

“These young children, having spent their early years immersed in Hong Kong’s Cantonese-speaking environment, already have a significant advantage over their BBC peers in mastering the language,” she said.

“But what I’ve seen is that they tend to lose the language very quickly if they stop using it entirely.”

New tech adds an edge

Back in Hong Kong, linguistics scholar Lau Chaak Ming has been spearheading a project to build, maintain and promote a free Cantonese input keyboard app called TypeDuck.

“We wanted to create an app that allows learners of Cantonese to type in Chinese characters even before they reach a high level of proficiency,” Dr Lau, an assistant professor at The Education University of Hong Kong, told ST.

TypeDuck – which sounds like “type dak”, or “can type” in Cantonese – allows one to easily type Cantonese words using their approximate Jyutping pronunciations.

The keyboard also provides word translation prompts in English, Hindi, Indonesian, Nepali and Urdu.

These prompts are aimed at helping Hong Kong’s ethnic minority groups – which make up over 8 per cent of its 7.5 million population – communicate in Cantonese by using just the approximate spelling of the sound, without having to know how to write the Chinese language in strokes.

TypeDuck – which sounds like “type dak”, or “can type” in Cantonese – allows one to easily type Cantonese words using their approximate Jyutping pronunciations.

PHOTO: TYPEDUCK

The app, supported by a HK$2 million (S$336,000) language fund approved by the Hong Kong government in 2021, has received good reviews and is highly recommended on various digital platforms, with a 4.8 rating out of five stars on the Apple App Store.

“TypeDuck… inspired (me) to finally learn Jyutping and re-master my Cantonese,” US-based engineer Janan Zhu wrote on Instagram Threads.

Dr Lau and his team have held training workshops on the app for teachers and students at over 20 schools across Hong Kong as well as one at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

“It’s still early days, but I’d say learners are now more positive towards learning Jyutping and Cantonese,” the academic said.

He added, however, that native speakers who refuse to learn the romanisation system remain an obstacle to promoting the language globally.

The TypeDuck keyboard also provides word translation prompts in English, Hindi, Indonesian, Nepali and Urdu.

PHOTO: TYPEDUCK

Jyuttoi’s Mr Wong was of the same view.

“I wish Cantonese education in schools could be made more systematic, and that native Cantonese speakers would also be taught the phonetics of the language,” he said.

“If as native speakers ourselves we don’t know Jyutping, it makes it really hard for us to go out to teach foreigners about our language.”