Australia’s infrastructure boom: Future-proofing or just catching up?

Major airport, road and rail projects across Australia are reshaping the nation to serve its growing population and underpin economic growth for years to come. But are these massive projects enough? And can the country afford the huge price tag? Jonathan Pearlman in Sydney puts on his hard hat to investigate.

Sign up now: Get insights on Asia's fast-moving developments

A first-ever train tunnel beneath Sydney’s harbour is a key link in a A$65 billion expansion of the city’s train network.

PHOTO: SYDNEY METRO

SYDNEY - In early August 2024, the ribbon will be cut on a A$21.6 billion (S$19.5 billion) rail project in Australia that involves the first-ever train tunnel beneath Sydney’s harbour.

The driverless trains will whisk passengers at speeds up to 100kmh across the harbour, completing the 4km journey between the stations on either side in three minutes.

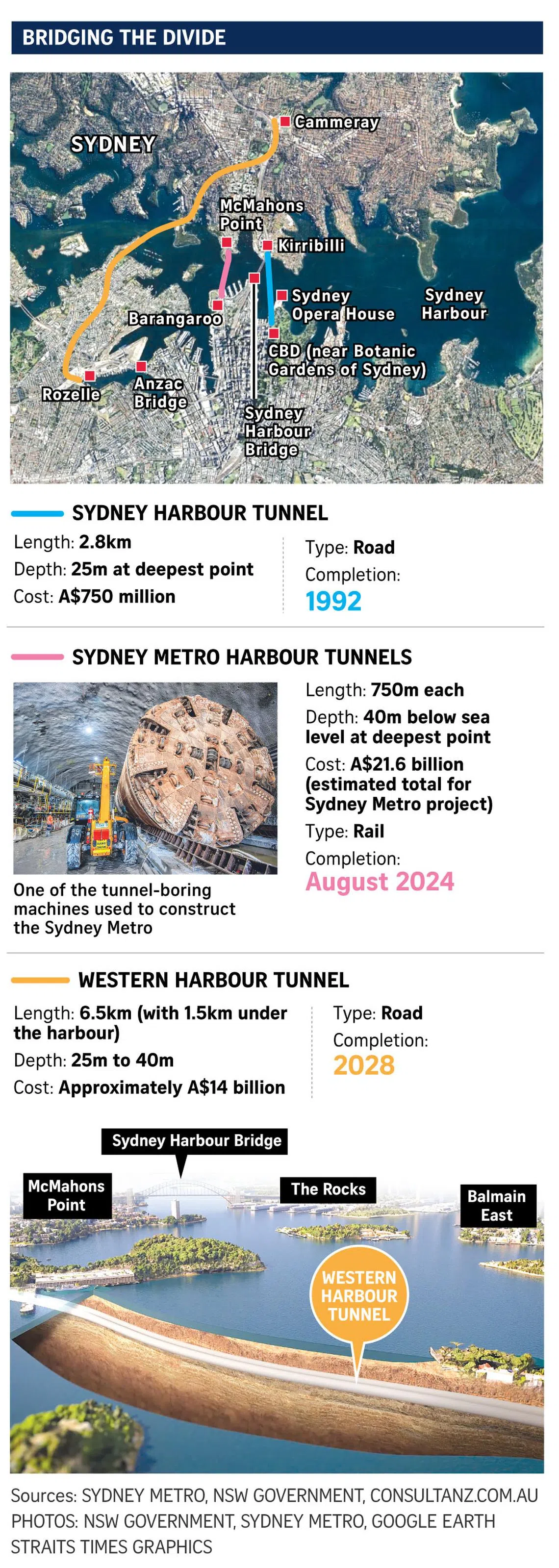

The tunnel has been built up to 40m beneath the water’s surface, about 15m below the only other tunnel under the harbour – a roadway that opened back in 1992.

The harbour crossing is part of a new 15.5km rail line, from the suburb of Sydenham in Sydney’s south-west to Chatswood in the north.

It is a key link in a A$65 billion expansion of the city’s train network that marks the biggest transport project in Australia’s history.

New lines and stations have been opening across the city since 2019 and will continue to do so until 2032, boosting rail capacity to 40,000 passengers an hour, up from 24,000 currently.

In south-western and northern Sydney, residents have been keenly awaiting the opening of their new line. Discussing the project this week, Mr Peter Olive, a resident of south-western Sydney, told The Straits Times: “The Sydenham to Chatswood line is fantastic.”

Mr Olive criticised the state government’s conversion of some existing rail lines into new lines, saying this was wasteful and unnecessarily disruptive to local communities.

But he was enthusiastic about the soon-to-open harbour tunnel, which will provide extra rail capacity and help to address worsening congestion in this city of 5.5 million people.

“This is a new rail line,” he said. “It is new mass transit in Sydney. It takes us away from cars,” he said.

But this highly anticipated cross-harbour rail line is just a small component of a massive infrastructure boom that is happening in Sydney and across Australia as the nation urgently tries to make up for a failure in recent decades to build enough transport and other services to accommodate its surging population.

The new projects are expected to ease congestion and ensure residents of fast-growing cities have ready access to jobs, schools, hospitals and other services.

On June 24, as the New South Wales government confirmed plans to open the harbour rail tunnel within weeks, it also announced that a new 10km tunnel had been completed on a separate line that will take passengers to a new international airport, Western Sydney Airport, which is due to open in 2026.

Western Sydney Airport, which is under construction, is due to open in 2026.

PHOTO: WESTERN SYDNEY AIRPORT

Work is also under way on a new roadway that will include yet another tunnel under the harbour – the third – which is due to open in 2028 and will be for road traffic.

But the transformation is not limited to Sydney.

In Victoria state’s capital Melbourne, which has 5.2 million residents and is Australia’s second-most populous city, a A$10.2 billion underground roadway – the West Gate Tunnel – will open in 2025.

It will ease congestion off a bridge that connects the city centre to the west and currently carries about 200,000 vehicles a day.

The state is also embarking on its biggest and most ambitious project – a rail loop around the city that includes a A$13 billion train line, due to open in 2029, which will finally connect the city centre to the airport.

One of the tunnel boring machines used to create the West Gate Tunnel in Melbourne.

PHOTO: STATE GOVERNMENT OF VICTORIA

Elsewhere, Perth in Western Australia is rolling out a A$10.5 billion rail expansion – with 72km of new lines and 23 new stations – that is its biggest-ever public transport project.

And the state of Queensland has begun a A$13 billion upgrade of a 1,673km highway – including 109 new bridges – that connects Brisbane to the northern city of Cairns, due to be completed by 2028.

Meanwhile, new light rail networks have opened in the federal capital Canberra and in the Gold Coast, and a A$31 billion inland rail project will provide a link for heavy freight from Brisbane to Melbourne.

These projects are radically transforming Australia and reshaping the daily lives of its 27.3 million residents. But they are also raising concerns about the environmental impacts and about affordability as the country’s debt and inflation rise.

And they are raising questions about why the country is embarking on this unprecedented boom, and whether it will see the country into the future or merely address a backlog that has been decades in the making.

To appreciate the growing need for infrastructure in Australia, an obvious starting point is the region of western Sydney, the fastest-growing part of the city.

Victoria Cross station is part of a new 15.5km rail line that runs from Sydenham in Sydney’s south-west to Chatswood in the north.

PHOTO: SYDNEY METRO

Home to 2.65 million people, residents in the area struggle with dire traffic and inadequate access to rail lines and other transport services.

In April 2024, an annual survey conducted for the past 16 years by NRMA, a roadside assistance firm, found that western Sydney had – for the first time – overtaken the central business district as the city’s most congested area.

A western Sydney resident, Mr Wayne Willmington, a 64-year-old father of two who has lived in the suburb of Luddenham his entire life, said transport options in the area have failed to keep up with the surging population. Asked about the traffic, he told ST: “It is disastrous.”

Mr Willmington, who works for a local radio station, said his nephew travels to school by public bus and is “late every day” due to the traffic. He said local residents try to avoid travelling during peak hours, from about 7am to 9am and 4pm to 6pm.

“Unless you have to travel in peak hours, you don’t,” he said. “Because of the high amount of new residences, and new housing estates setting up, it is just more and more people here. You try to work so that you are not driving in peak times. If you need a meeting, you schedule it so that you can avoid peak times.”

These growing urban pressures are occurring across cities throughout Australia, due to a surge in population that has placed intense demands on existing transport, roads and other services.

In recent decades, waves of migrants – especially from China, India and the United Kingdom – have fuelled a 75 per cent increase in Australia’s population since 1986, when it was 15.6 million.

In 1986, the proportion of Australians who claimed Chinese and Indian ancestry was 1.1 per cent and 0.3 per cent, respectively; according to the census in 2021, these proportions had increased to 5.5 per cent and 3.1 per cent.

An expert on transport and road infrastructure, Dr Kasun Wijayaratna, a senior lecturer at the University of Technology Sydney, told ST that Australia had failed to build enough infrastructure in the past 30 years to keep up with its population demands. He said the failure was partly due to Australia’s move to restrain spending after a severe recession of the early 1990s.

“We are definitely going through quite a significant infrastructure boom,” he said. “If you look at the 1990s and 2000s, there was not much infrastructure development. During the 1990s we went through a recession and had a lot of conservative decision-making focused on stabilising the economy and on economic growth, and they felt it was a risk to invest in infrastructure.”

An artist’s impression of the entrance to Melbourne’s West Gate Tunnel, which is due to open in 2025.

PHOTO: STATE GOVERNMENT OF VICTORIA

But Dr Wijayaratna said the current boom will do more than just catch up with demand and is set to improve travel times and liveability in major cities.

“The trajectory that we’re on is quite optimistic,” he said. “Western Sydney Airport is a great example of infrastructure that has been required for many years. We finally committed to it. I see it as a forward-looking approach.”

Indeed, Western Sydney Airport, the city’s second international airport, is expected to not only increase flight options but also help to attract massive new infrastructure, including housing and businesses, to a newly developing part of the city.

The airport is due to accommodate 10 million passengers a year from 2026 and will operate 24 hours a day. Though the airport’s airlines and destinations are still being determined, Australia’s national carrier, Qantas, and its low-cost subsidiary Jetstar have announced plans to operate from the airport during the first year, including to popular domestic destinations such as Melbourne, Brisbane and the Gold Coast.

New roadways are being built around the airport, which will also include two new rail stations. And a new urban development near the airport is expected to have 10,000 homes as well as a business precinct and some pedestrian-only streets.

The Federal Minister for Infrastructure and Transport, Ms Catherine King, has described the project as a “transformational infrastructure project” that had already generated 4,300 jobs.

“This significant piece of infrastructure... benefits not just the west but the whole of New South Wales,” she said in a statement on April 11.

But the infrastructure boom has prompted questions about whether Australia can afford such massive expenses, especially as inflation and interest rates rise.

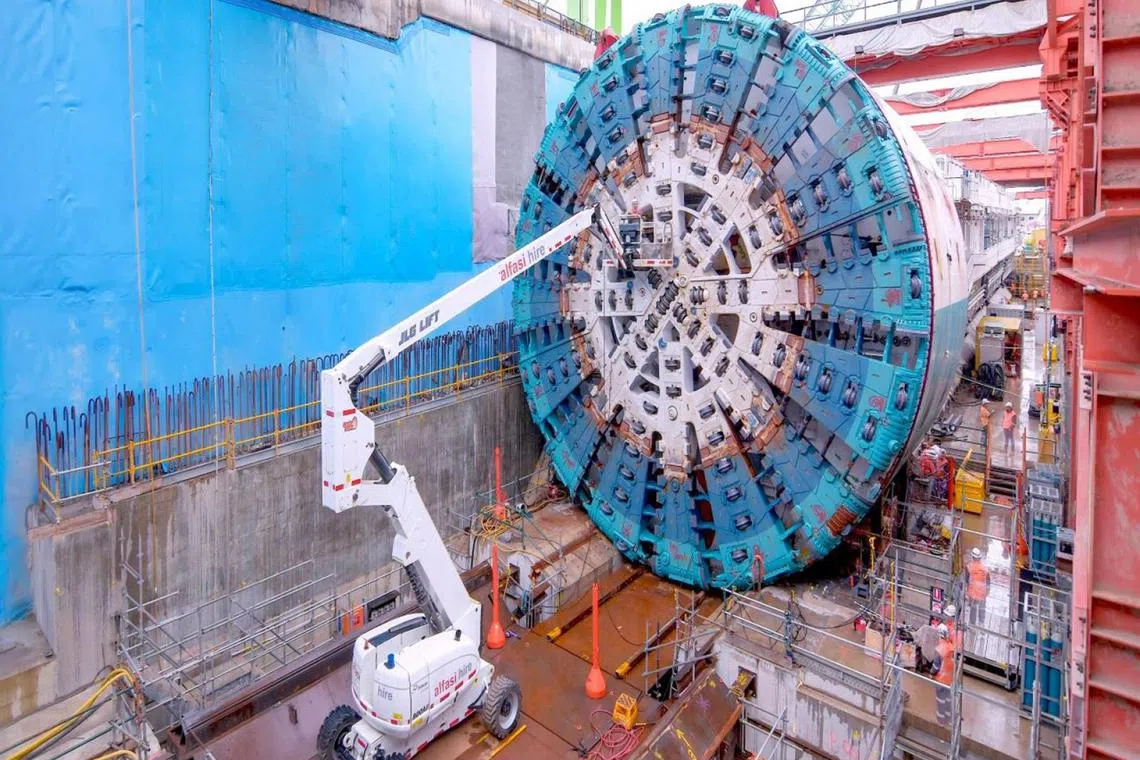

One of the tunnel boring machines used to construct the Sydney Metro.

PHOTO: SYDNEY METRO

Much of the investment in major infrastructure in Australia is funded by state and federal governments, though some involve partnerships with the private sector. Foreign investment is accepted, except for projects that are deemed sensitive and vulnerable to potential national security threats such as telecommunications networks.

The federal government’s gross debt is about A$900 billion, an amount that has held relatively steady in recent years. But states’ total debt is due to reach A$800 billion by 2028, up from just A$266 billion in 2019, according to a report in The Australian Financial Review on June 19.

The high debt and heavy infrastructure spending have prompted warnings that they risk fuelling inflation in an economy where unemployment is already low.

An economist, Mr Chris Richardson, who runs the Rich Insight website, told ST that Australia has high population growth compared with other developed nations. He said Australia has relatively low public-sector debt and could afford to spend large sums on infrastructure but should be concerned about fuelling inflation.

“I am not enormously worried about the debt problem,” he said.

“Construction-related costs have been a very fast-moving component of Australia’s wider inflation problem. There is a case for slowing down what is happening or cancelling some projects,” he added.

The boom has also raised concerns about the environmental impacts, particularly the effect on carbon emissions from boosting road networks and the large-scale construction projects that use large volumes of steel, cement and energy.

In Victoria, the state’s independent advisory body on infrastructure, Infrastructure Victoria, has proposed introducing a value per tonne of carbon emissions to help guide decisions on building new roads, rail and other projects. It also wants the state government to consider reducing the number of large-scale projects and instead look at solutions that avoid building altogether, such as through using traffic lights to ease congestion.

Dr Wijayaratna said planners will increasingly need to consider “greener” infrastructure options. He said the authorities should look to expand uses of existing infrastructure, for instance, by using multilevel carparks when they are empty on weekends for markets or community events.

But the infrastructure boom is, for the most part, being greeted with a collective national sigh of relief. Though some projects have involved hefty delays and overspends, the overwhelming consensus is that the upcoming roads, tunnels, rail lines, bridges and other services will help to address rising population pressures that are making parts of major cities unworkable.

The head of the urban think-tank Committee for Sydney, Mr Eamon Waterford, told ST that the new rail line and other projects were set to make the city more accessible and more liveable. But he said large projects take decades to plan and build, and the next step was to start preparing for the needs of the future.

“We are in a golden age of new infrastructure opening up for people,” he said. “Many of those projects have been in planning for decades. The real benefits that we are deriving from them now have to motivate us to keep going.” Jonathanmpearlman@gmail.com