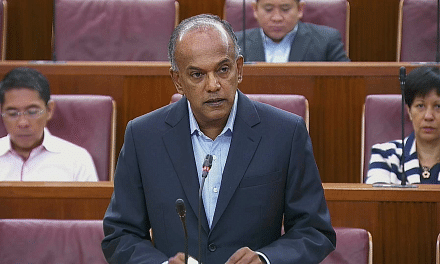

SINGAPORE - Trust in public institutions, like the government or the media, is essential in creating an environment to share facts thanks to a belief in authenticity of the sources, Home Affairs and Law Minister K. Shanmugam said in Parliament on Tuesday (March 7).

But "new media has been heavily exploited to batter this infrastructure of fact", which in turn weakens trust in public discourse, institutions, and democracy itself, he said during the start of the debate on the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Bill.

The minister expounded on three sources of online falsehoods: foreign countries using information warfare; those who seek commercial profit; and deliberate actors who send falsehoods for political ends or to harm other groups.

Falsehoods from such groups "have been weaponised, to attack the infrastructure of fact, destroy trust and attack societies", he said.

FOREIGN COUNTRIES USING INFORMATION WARFARE

The rules of war have changed, with some foreign countries using non-military measures like information operations to "harness the protest potential of the population", Mr Shanmugam said.

Such operations mean stoking opposition in a target country, to create a permanently operating front, he said, adding that such non-military measures can exceed the power of force and weapons.

"Even though military or overt violent measures are not being used, the target states' national security and sovereignty are threatened and violated," he said. "The lines between war and peace have now been blurred."

He said experts who spoke to the Select Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods last year noted that Singapore's military superiority in the region means it would be futile to start a war here.

"Military weaker countries will then focus on other means to weaken Singapore, sap our will from inside, create deep internal divisions," he said.

This was already happening, with people trying to weaken support for the Singapore Armed Forces or shift Singapore's foreign policy, he said, without giving details.

Among his international examples included one in Germany, where a girl fabricated the claim that she had been assaulted by three Middle Eastern migrants.

Even though Berlin authorities found the case to be fake, falsehoods that the police were covering up the case were circulated online, leading to thousands to take to the streets in protest.

That same year, a far-right populist party made unprecedented gains at the regional elections - many from the same constituency as the girl who made the fake claim.

COMMERCIAL PROFIT

Another reason some spread falsehoods through new media is for profit.

"Digital advertising models have turned websites into virtual real estate," Mr Shanmugam said. "With every click, digital ad revenue is earned."

Such a business model has created an "attention economy", with content that stokes fear and anger good for attracting attention.

These falsehoods not only earn people large sums of money, but also have political impact, he said.

He cited the example of American Paul Horner, who set up at least 20 fake news websites with deceptive URLs to trick readers into thinking they were reading from mainstream sources. He made at least US$10,000 a month from Google AdSense, said the minister.

One false article said protesters were paid to protest against then presidential candidate Donald Trump, which was retweeted by his campaign .

DELIBERATE ACTORS

Other times, both local and foreign civilians spread falsehoods for political reasons or out of personal prejudices, affecting their own as well as other countries, said Mr Shanmugam.

For example, he pointed out that alt-right groups in the United States drove false narratives during the 2016 US presidential election campaign, and also reached across the Atlantic to support such politicians in Germany.

"Populists use lies to attack institutions, invoke divisive rhetoric... The truth becomes completely irrelevant," he said. "Even the most extreme lies, which we will normally dismiss, become believed and impact public life."

He gave the example of the Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom, where immigration was a hot topic and many false claims and fake stories were concocted.

One of them was about how there are some areas where syariah law dominates and non-Muslims cannot enter.

While outlandish, 32 per cent of a survey of 10,000 people in 2018 believed the falsehood about "no-go" areas was true.

It also created a permissive environment for hate, with a 41 per cent spike in hate crimes after the referendum, he noted.

Mr Shanmugam said falsehoods are used "to divide and polarise", making democratic discourse, accommodation, and compromise difficult.

"In these conditions, the political centre becomes hollowed out, and people are driven to extremes," he said.

He added that psychological evidence shows that mere exposure to conspiracy theories, even if they are dismissed, makes people less likely to accept official information or to engage in politics.

The result is that people may mistrust the very existence of a shared body of facts, and "disengage from public discourse altogether".