LONDON • Ms Martine Wright knew she was late for work in central London, so she jumped into the wrong underground train, hoping that this would get her closer to the office.

She never made it. Instead, she recalls seeing her train carriage explode, and found herself in a heap of twisted metal and mutilated bodies. She lost 80 per cent of her blood, had both legs amputated and spent 10 days in a coma. But, as she frequently reminds people, she was the lucky one, for in three additional terrorist explosions in other parts of London, 52 people died and a further 700 were maimed.

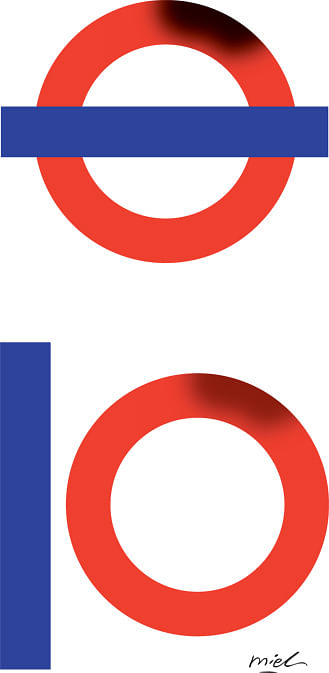

Tomorrow, London marks a decade since that tragic July 7, 2005, morning with a sense of justifiable pride. No one who witnessed the carnage would easily forget the bravery of firefighters and paramedics who descended into dark and smoke-filled underground tunnels aware that they could face further bombs, or the surreal sight of hundreds of doctors rushing out to help with their bare hands the victims of a bus that exploded near the building where they happened to be holding a convention.

The very next day, most Londoners used the same underground railway network to go to work, and the heavily armed soldiers and policemen who guarded every station still managed to smile while greeting passers-by. Few nations are better than Britain at confronting disasters with such a stoic, grim determination.

But although the "7/7 bombings", as they are now popularly known, have spawned a whole new approach to tackling domestic terrorism and a raft of security measures now adopted by governments worldwide, the fundamental threat of terrorism remains unchanged: British flags have flown at half-mast during the past weekend in memory of the 38 tourists, mostly Britons, recently murdered on a beach in Tunisia.

In terms of sheer carnage, the London bombings are overshadowed by the Sept 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in America and by the explosions in trains in the Spanish capital of Madrid in 2004, where 191 people were killed and a further 1,800 were wounded.

DOMESTIC TERRORISM

Still, London's 7/7 atrocity was the first big example of suicide attacks generated by domestic terrorism, since all the four bombers were British-born and raised. As Mr John Stevens, who commanded London's Metropolitan Police, put it at the time, the terrorists did not "fit the caricature (of an) Al-Qaeda fanatic from some backward village in Algeria or Afghanistan".

The realisation that some British young men were prepared to leave behind the gentle West Yorkshire hills in northern England, where they were born, in order to blow themselves up in London trains and buses, with the explicit mission of murdering as many of their co-citizens as possible, seemed shocking at that time. But in many respects, the individual profiles of the terrorists who perpetrated the London attacks provided an early warning to security services worldwide that the men of violence do not fit, and probably never will fit, into established stereotypes.

-

The clearest proof that all of Europe's counter-radicalisation programmes launched after London's 7/7 bombings had no practical outcome emerges from the current wave of European volunteers travelling to Iraq to join the ranks of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria terrorist group.

Although many Islamic terrorists claim and are assumed to be very pious, few really are, as the London example showed. Germaine Lindsay, who blew himself up in a train travelling from London's King's Cross station a decade ago, killing 26 people, spoke no Arabic, was brought up as a Christian and converted to Islam only shortly before his death. It is certain that, at the tender age of 19, he knew next to nothing about the faith.

And Shehzad Tanweer, an accomplice who blew up another train, was having an affair, something considered a major sin even in liberal Islamic circles. In short, such people do not die for a religion, but for their own warped ideology in which the Islamic faith is used as merely a highly selective backdrop.

And, as the London attacks indicated, suicide bombers are neither poor nor necessarily socially excluded.

Two of the terrorists had wives and young children, all came from stable middle-class families, and members of the family of one of the terrorists were previously invited to tea with Britain's Queen Elizabeth II because they were seen as good promoters of integration into local society.

NEW MEASURES

The realisation that those prone to terrorism may be less unusual, less freakish and more outwardly ordinary than previously assumed spawned massive counter-radicalisation programmes in Britain and many other European countries.

Initially, Britain's signature counter-radicalisation programme, which bore the title "Prevent", was hailed as a great innovation as it sought not only to stop would-be terrorists, but also to discredit extremism itself, by steering young people away from violence.

But as British Home Secretary Theresa May later admitted, the programme failed, because "it confused the delivery of government policy to promote integration with government policy to prevent terrorism. It failed to confront the extremist ideology at the heart of the threat we face; and in trying to reach those at risk of radicalisation, funding sometimes even reached the very extremist organisations that Prevent should have been confronting". Similar but less well-funded projects in Germany and France also faded.

The clearest proof that all of Europe's counter-radicalisation programmes launched after London's 7/7 bombings had no practical outcome emerges from the current wave of European volunteers travelling to Iraq to join the ranks of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) terrorist group.

And, once again, British volunteers are making a particularly grisly contribution to the wars in the Middle East: The knife-wielding executioner who became known to the world as "Jihadi John" in the videos released by ISIS was raised in a middle-class area of north-west London.

And British young women also seem to be leading a new trend - of female volunteers travelling to Iraq in order to become sex slaves for local terrorists.

RETURNING TERRORISTS

The fear is that, although many of these volunteers will be killed in the current Middle East fighting, a sufficient number of them will return, providing the basis for the next generation of European terrorists. Lord Alexander Carlile, one of Britain's best lawyers, who was appointed to oversee all the anti-terrorism legislation, initially believed that the threat of domestic terrorism in his country would last for about a generation. Recently, he admitted that "I think we were probably looking at a generation and a half".

LESSONS FROM 7/7

Still, both Britain and many other countries are safer today as a result of lessons learnt from the London tragedy. Britain's security services have done an excellent job at penetrating various terrorist networks and dismantling them. An average of five potentially significant terrorist plots were foiled each year over the past decade. The fact that Britain has not experienced a major terrorist attack since 2005 is remarkable, particularly when one considers that during that period London hosted the Olympic Games.

The cooperation between various national intelligence services is better today than a decade ago. Legislation has given security services greater powers to nip terrorist networks in the bud. Technological advances are helping intelligence agencies in "joining up the dots" by identifying suspect individuals who may be engaged in activities that look inoffensive, but ultimately result in the recruitment of new terrorists.

"Relational" software that constantly queries computerised databases to aid investigations by identifying trends that may not be obvious to the naked eye, better face-recognition software that looks for suspects in closed-circuit television camera footage, as well as many other innovations - all have been boosted because of the London tragedy a decade ago.

Emergency services worldwide have also studied extensively the lessons drawn from the 7/7 bombings. Modular urban transport control systems that can be switched off in portions, rather than having an entire network shut off, are now the norm in many big European cities. Britain's Joint Emergency Services Interoperability Programme, which seeks to improve the ways in which the police and fire and ambulance services work together in emergencies, is being adapted by other countries. And the British model of a small unit based in the Cabinet Office in London that can swing into action to handle a major crisis is also being exported to other nations.

The worst can still happen. But many nations are now prepared to give the best they can under such circumstances.

Ultimately, the men of violence may not disappear, but they are being marginalised and will be forgotten. Far from being hailed as heroes - as they dreamt they would be - the four London bombers have their names remembered by few.

But that is not the case for Ms Wright, who proudly pushed her wheelchair behind the British flag as part of her country's team for the London Paralympics in 2012. It is not the terrorists, but people like her, who represent the future.