The second-quarter figures released by the Ministry of Trade and Industry last week painted a bleak picture.

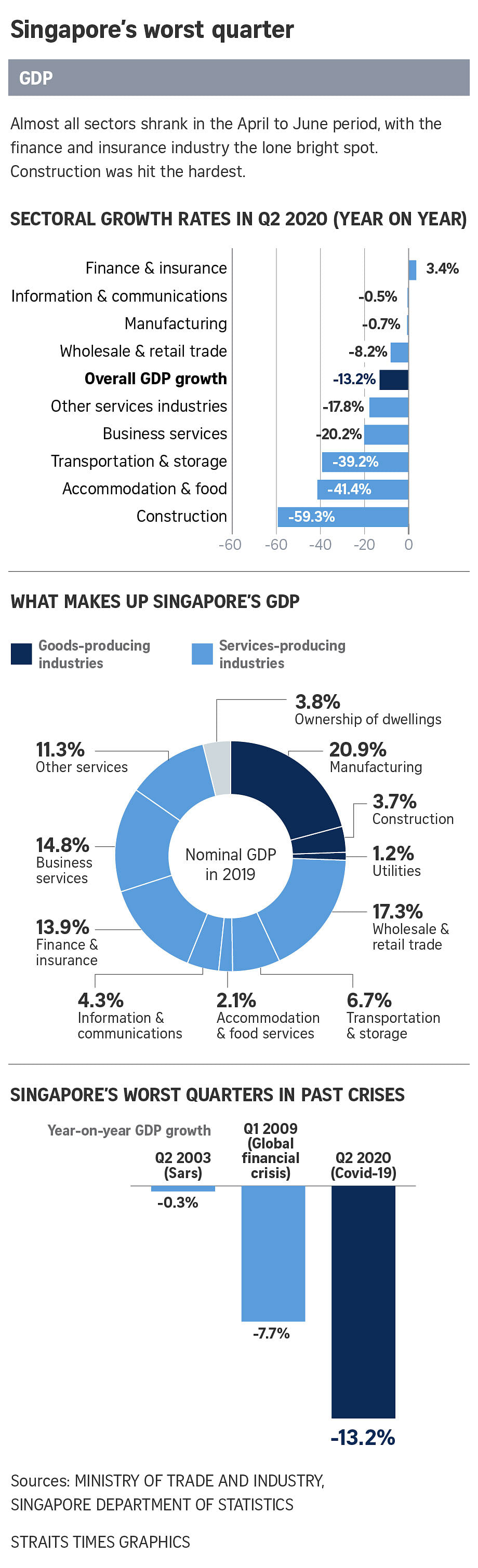

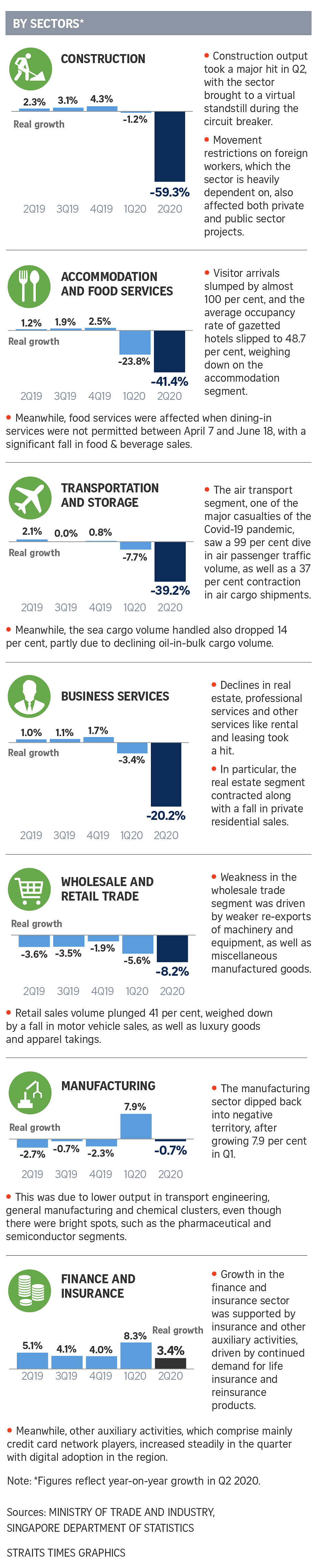

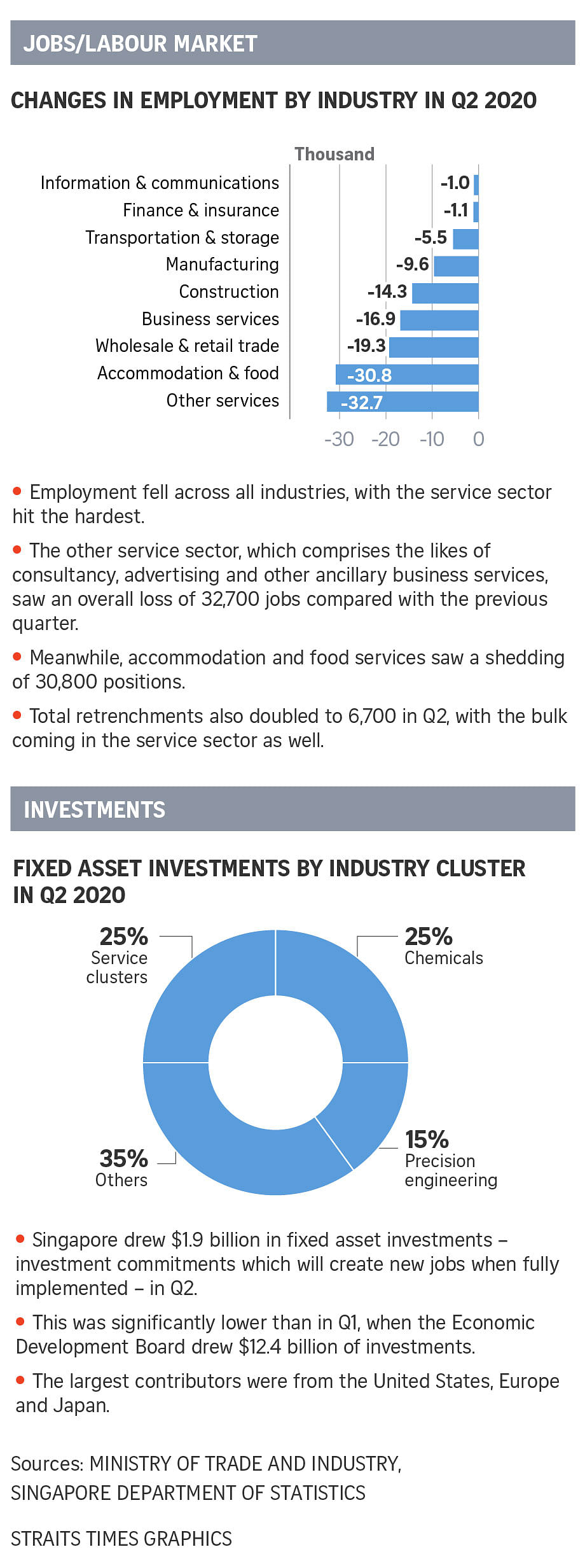

In the second quarter, the economy contracted by 13.2 per cent year on year - the worst quarterly contraction on record.

Gross domestic product (GDP) shrank by 6.7 per cent in the first half of this year, and is expected to contract by 5 per cent and 7 per cent for the full year.

With government revenue expected to take a significant hit, it is unlikely that the Government will run a balanced budget or surplus next year, says National University of Singapore economics lecturer Chan Kok Hoe.

If the economy has not fully recovered, cutting expenditure or raising tax rates would be a big no-no, he says. This means the Government could end up dipping into past reserves again.

In June, President Halimah Yacob gave the go-ahead to fund support packages that could draw up to an additional $31 billion from Singapore's past reserves.

Taken together, the four Budgets this year commit close to $100 billion - or nearly 20 per cent of GDP - in Covid-19 support measures.

How much more public spending is needed - and how much of the reserves the Government should draw on - are likely to be raised after Parliament reopens on Aug 24.

At the heart of the long-running debate on reserves is the issue of intergenerational equity.

Successive ministers have argued that because previous generations saved and built up the reserves, future generations must be responsible stewards of these reserves.

But coexisting with this is what an 2018 Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) working paper calls a more "distributive" interpretation - that present generations have an obligation to improve the lives of the less well-off within each generation, instead of accumulating excessively for the future.

This is a position that opposition MPs such as Workers' Party chief Pritam Singh and various academics appear to lean towards, having pushed for the 50 per cent cap on the Net Investment Returns Contribution (NIRC) to be raised temporarily.

Under the Net Investment Returns framework, the Government can spend up to 50 per cent of the long-term expected real returns, including capital gains, on relevant assets.

This strikes a balance between spending on Singaporeans' needs today, and growing the size of the reserves for future generations.

CHANGING ECONOMIC TRENDS

The calls for greater redistribution also coincide with changing trends in economics.

Over the past decade - and increasingly as Covid-19 wreaked havoc - policymakers around the world have relaxed their positions on minimum wages, inflation and public debt, and taken a stronger interest in poverty and inequality.

Analysts tell The Sunday Times that Singapore still has considerable fiscal space and has not reached a cliff edge where it has no choice but to raise the cap on NIRC.

But one way to resolve the debate in a less politically sensitive way, says Singapore University of Social Sciences' Professor Walter Theseira, is to define rules that trigger the usage or availability of a certain portion of the reserves.

"The NIRC cap should be dynamic in that it could vary depending on the value of public expenditure at that point in time, and the opportunity cost of leaving the funds to accumulate," he says.

He adds that greater use of the NIRC and reserves can be triggered when GDP growth is below trend, or when unemployment rises.

Others point out that options such as borrowing can be explored without dramatically changing the Government's commitment to fiscal prudence.

NUS' Mr Chan says interest rates are low and are expected to remain so for some time, making the climate for financing deficits by borrowing more conducive.

Major central banks have been supporting government bond issues via their quantitative easing (QE) programmes.

But this has to be thought through carefully as the Singapore dollar is not a reserve currency, and the weak inflation response to QE programmes in Japan, the European Union and the United States may not apply well, says Mr Chan.

"Whether to use borrowing or to draw down past reserves - in other words, sell financial assets - depends largely on what one thinks about how the value of these financial assets will change over time.

"I don't think there's a clear-cut answer, so I would not rule out keeping the status quo."

Deputy Prime Minister Heng Swee Keat said in Parliament this year that the Government will not borrow to pay for recurrent spending that benefits the current generation, on the grounds of prudence, intergenerational equity and concern that such debt will become unsustainable, as the economic outlook is uncertain.

But he said that it is reviewing borrowing to finance major long-term infrastructure that will benefit multiple generations. This could include the expansion of Singapore's rail network, as well as infrastructure to deal with climate change.

IPS senior research fellow Christopher Gee cautions that even this important source of funding could shrink, if the current low or negative interest rates persist in the long term.

Beginning in 2016, NIRC has overtaken corporate income tax to become the main source of budget funding, exceeding all previously conventional sources of revenue from taxes.

Sharing Mr Gee's concern is DBS senior economist Irvin Seah, who says the more the returns on reserves are used, the less there will be left to plough back into the reserves. This means it will be a tougher slog to build up the war chest.

Mr Seah says that since the reserves are such a strategic asset for Singapore, the point is whether the Government should set what could be an unhealthy precedent.

"We must appreciate the trade-off between tapping more for short-term needs, versus long-term reserve accumulation that will benefit future generations," he says.

"No one can be sure that there will not be an even bigger crisis ahead. If we don't maintain fiscal sustainability, the next time we enter a crisis like Covid-19, we will all be less prepared."