Late last month, German Chancellor Angela Merkel quietly dropped a bombshell. Speaking at a political campaign rally in a beer-tent in Munich, she told Europeans that they could no longer depend on America. Europeans must "take our fate into our own hands", she said, because "the times in which we could rely fully on others - they are somewhat over". Her words are not just important for Europe; they carry a message for Asia, too.

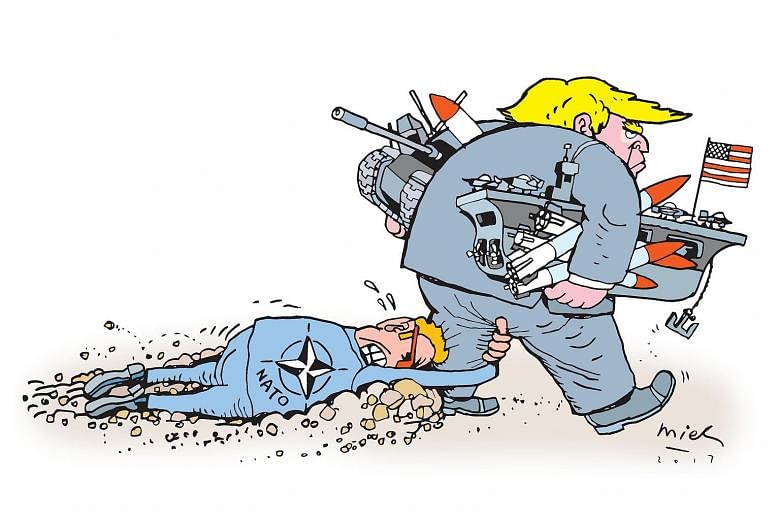

The immediate cause of her remark is clear. She had just come from a Nato summit where United States President Donald Trump had very deliberately refused to endorse the critical Article 5 of the Nato Treaty - the clause which commits its members to come to one another's aid with armed force. But Dr Merkel is not the kind of leader to decide a fundamental question on this basis alone, or even on Mr Trump's long record of scepticism about Nato.

The real source of Dr Merkel's anxiety about US commitment to European security goes much deeper. It reflects fundamental shifts in the basis of global order and America's role in it, as the post-Cold War mirage of unassailable US leadership dissolves to reveal a much messier and more dangerous reality.

After the Cold War, America's willingness to take the lead in Europe's defence was easy to take for granted, because Europe faced no major threats. But Russian President Vladimir Putin's aggressive moves against Ukraine have shaken Europe's complacency. It is no longer fanciful to imagine that Russia could attack a Nato country - especially the Baltic states which were once part of the Soviet Union.

How would America respond? In 2014, then President Barack Obama formally reassured the Baltic states and the rest of Nato that America would fight to defend them, and he deployed US forces there, and in Poland, to show he was serious. But doubts remain. The military reality is that Russia's revitalised forces would far outweigh Nato's in the critical first days of a conflict. There would be no swift and easy American victory.

Instead America would take months to deploy its full strength across the Atlantic, and then face a very gruelling campaign against the formidable Russian military, fighting on its own doorstep. The fight would be long and hard, with no guarantee of ultimate victory, and a real chance of nuclear catastrophe.

Would America really do all this? During the Cold War the answer was yes, because the mighty Soviet Union seemed poised to roll over the whole of Europe, dominate the entire Eurasian landmass and threaten America's homeland in the Western hemisphere.

But Russia today, for all Mr Putin's sinister designs, does not pose that kind of threat to America itself. So why should America risk so much to defend the Baltics? Or even Poland?

That raised deep questions about how seriously Europeans could trust president Obama's promises. And it provides the context for what President Trump has said - and what he has not said - about Nato.

Mr Trump won the presidency last year promising to step back from America's alliance commitments and make its allies look after themselves. He seems to have no conception that those alliances can serve US interests, because he defines US interests much more narrowly than his predecessors have done. And, of course, he is much less hostile to President Putin than his predecessors have been.

And this is not just about Mr Trump. His election overturns assumptions about how Americans at large feel about their country's global role. Until his victory, everyone assumed the overwhelming majority were wedded to the idea of US global leadership, and are willing to accept the costs that go with it. Now it is clear that is not so. The US foreign policy establishment may shudder when Mr Trump scorns Nato, but the voters don't seem to mind.

All this means that any prudent European leader must seriously ask whether it is any longer sensible to rely on America's commitment to their security. And that is exactly what Dr Merkel was doing last month in Munich. It will be fascinating to see where the issue goes from here.

ASIA LACKS AN ANGELA MERKEL

Meanwhile in Asia we face very similar questions. We too live in a region which has remained peaceful for decades, thanks to a stable regional order supported by America's strategic commitment. We too find that this is now being challenged by a major regional power. We too must ask how confident we can be that America has the strength and resolve to sustain its strategic leadership in the face of that challenge. And we too must recognise that our doubts are redoubled by the presidency of Mr Trump.

But there is a difference between Asia and Europe. Asia has no Angela Merkel. Perhaps the most striking thing about Dr Merkel's comments in Munich last month was the fact that she could, on such a momentous issue, credibly speak to, and for, Europe as a whole. She was the only figure in Europe who could do this. But there is no comparable figure in Asia with anything like the same standing, and thus no one we in Asia can look to for a lead in responding to the comparably momentous shift in our own strategic circumstances.

Of course, we have always known and understood that Europe's very different history and geography have provided the foundation for wider and deeper regional integration there that goes far beyond anything that would be possible, or even suitable, here in Asia. But there is no escaping the consequences of that when we face the kinds of strategic challenges that confront us today.

Notwithstanding all the stresses at work in Europe today, the continent has a sense of identity and structures for cooperation which at least provide options for a coherent regional response as America's leadership falters and fails. And they have a leader like Dr Merkel to take the lead in guiding the region towards a new order.

Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe might aspire to that role in Asia, but he cannot fulfil it. Perhaps if any regional leader could have done so, it would have been Singapore's Mr Lee Kuan Yew. He had the strategic vision, the personal standing and the political skills to offer a lead to the region in uncertain times. But there seems no one today who could step into those shoes. And that only makes Asia's strategic future all the more uncertain.

•Hugh White is professor of strategic studies at the Australian National University in Canberra.