The United States is the world's largest economy, China the second. China is the world's largest trading nation, the US the second. The two countries have long established the world's most important and consequential trade relationship, which is now under threat by US President-elect Donald Trump.

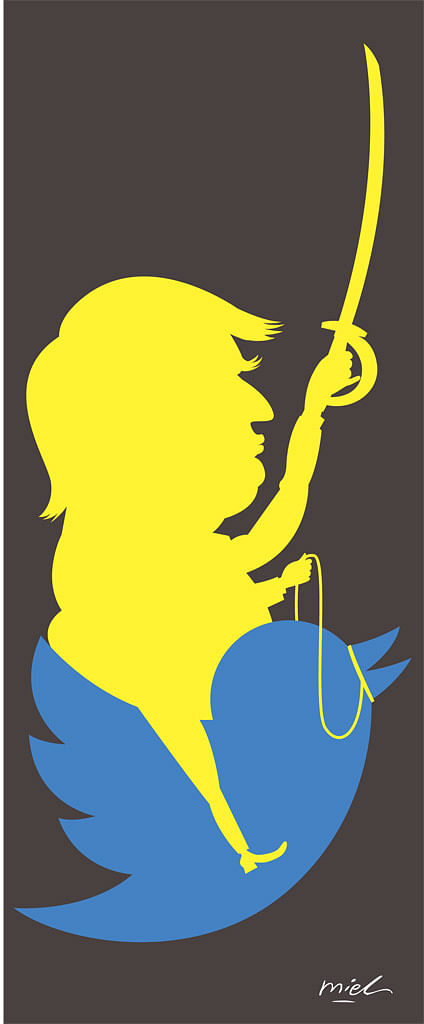

Mr Trump has brought about enormous uncertainty and serious concerns, not just to China but also to many other countries. His preferences for trade protectionism and anti-globalisation and his mercantilist approach to economic policies could harm the global economy.

Specifically, during his election campaign, Mr Trump singled out China as a potential target for trade sanctions. In fact, he made two fiery attacks on China.

First, he accused China of being a "currency manipulator" and said that he would instruct his Treasury Secretary to label China as such within 100 days of taking office.

Second, he charged China with "stealing American jobs" by dumping exports on the US and threatened to impose a punitive 45 per cent tariff on Chinese imports.

Both threats are serious. What worries Beijing and the rest of the world is how Mr Trump will follow through on them. It is unclear how he will play his "China economic card" once in office, and how he will translate his election rhetoric into concrete action and to what extent.

These external uncertainties could not have come at a worse time for China, with its economy slowing down amid rapid and difficult structural adjustment. This year is a politically significant one for China's leaders, as the 19th party congress is due to take place in November. The congress is held every five years to decide the country's future leadership. That is why good and stable economic growth is of grave importance to Beijing this year.

ANATOMY OF AMERICA'S CHINA ECONOMIC CARD

The charge that China manipulates the yuan exchange rate would have been relevant years ago, when China's economy was growing at double-digit rates, fuelled by an export boom. Today, however, such a charge of currency manipulation is simply dated.

Today, China's economic growth is driven by domestic consumption, with exports experiencing negative growth in recent years as rising wages - growing at double-digit rates for 10 years - and rising costs have seriously eroded its comparative advantage.

Accordingly, China's current account surplus in recent years has also come down, even though US trade deficits have continued to grow. Basic macroeconomics tells us that the root cause of the US' trade deficit is its overconsumption and undersaving, just as China's trade surplus is due to its high domestic savings.

Before 2014, the yuan appreciated more than 20 per cent against the US dollar. But today, it has become seriously overvalued, and fell 7 per cent against the dollar last year alone. Against a backdrop of rampant capital flight, the Chinese government has striven very hard to maintain the stability of the yuan exchange rate by tightening capital controls. Mr Trump's currency policy on China would likely bring about a perverse outcome.

By comparison, Mr Trump's threat to hit China on the trade front is much more credible - and potentially more damaging, particularly with the recent appointment of the anti-China hawk Peter Navarro to head the newly formed National Trade Council. Mr Trump clearly means business.

Just exactly how Mr Trump will launch his trade war against China is still unknown.

A partial trade restriction with sanctions against certain Chinese imports to the US through its trade remedy measure could breach World Trade Organisation rules. Full-scale sanctions against a wide range of Chinese products with punishing tariffs at 45 per cent would spell a trade war.

In 2015, two-way trade amounted to US$560 billion (S$800 billion). Last year, the US was China's largest export market, taking up 19 per cent of China's total exports, while China was only the third-largest export market for the US, with a 10 per cent share.

As China is exporting far more to the US, a trade gap has naturally arisen, with the US incurring a large trade deficit of US$366 billion for 2015, though it is only US$260 billion by Chinese accounts.

China's persistent trade surplus with the US has become a constant source of trade friction between them. But the real size of China's trade surplus has been exaggerated. US exports to China are mostly agricultural products (cereals) and primary commodities (minerals) and some advanced manufactured items such as aircraft and cars, all with a very high degree of domestic value-added.

In contrast, China's exports to the US are mostly electronics and electrical machinery (telecommunications products and office equipment) and a wide range of labour-intensive, "Walmart type" products (furniture and footwear), with low domestic value-added for China.

The US could not easily replace the higher value-added imports from China. For China's labour-intensive imports, the US trade sanction could possibly open the door for substitutes from other emerging countries, but certainly not from domestic sources. The US economy is just too advanced and high-cost for import substitution of many labour-intensive foreign products. Such a policy would thus have little or no effect on US employment creation.

The bulk of China's manufactured exports are the result of numerous regional and global production networks based in China, with the made-in-China finished products made up of parts from other countries. The classic example is the iPhone, which yields only a small fraction of its total cost to Chinese labour for processing it. The iPhone's various component makers from Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and the US take up far larger shares of the total value-add.

SAVING JOBS?

Mr Trump's ultimate objective is to "save American jobs". In traditional economic theory, the links between China's overall trade surplus and overall US job losses are just too tenuous. While China has chalked up a huge surplus in its merchandise trade with the US, what American politicians have often ignored is that the US has regularly incurred a huge surplus in its services trade with China.

They have also ignored the positive externalities of China's manufactured imports, such as Americans enjoying low-cost products free of inflation and pollution. The heavy fog over China's big cities bears witness to the high social cost of pollution that China has not priced into its manufactured exports to the US.

Economic games can be win-win or lose-lose. A free trade agreement between two countries - in creating more trade - is a win-win for both, while a trade war - in whatever form - is potentially a lose-lose act. It would certainly be unimaginable for the world's two economic giants to engage in a real trade war.

The US economy, being the stronger and more advanced, has more cards to play against China, Mr Trump may well be thinking. That may be the case in a one-to-one conflict. However, a trade war - even a partial one - in this highly globalised world, with intricate commercial connectivity and linkages, is likely to produce a dynamic chain reaction that could bring down the global economy, with many unanticipated side effects that might boomerang back to the US domestic economy.

Since China has already established extensive trade links with its neighbouring economies and its manufactured exports to the US are tied to the region's supply chains, any potential US sanctions against Chinese imports could well produce a lot of collateral damage to China's neighbours. It will be a trade war nobody in Asia wants.

Mr Trump could, of course, just target a few key commodities or take specific measures against China's investment and merger- and-acquisition activities. But hurting China's economy in such a way would hardly "make America great again".

CHINA'S WORST EXTERNAL THREAT

As China's economic growth has become much more broad-based and less dependent on exports, it has also become more resilient to external fluctuations. Nonetheless, the external uncertainties that China is facing today are unprecedented and likely the most serious since the start of its open-door policy in 1978.

The gathering uncertainty has already created a sense of imminent crisis that will hurt investment and consumption. Any whiff of a trade war or partial trade sanctions would undermine China's financial market and precipitate more capital flight, adding more pressure on the yuan.

China has put a high priority on maintaining reasonable stability of the yuan, which is crucial for its domestic financial and monetary stability. Serious yuan instability will also adversely affect China's exports, international business strategy, outgoing overseas investment and tourism, and undermine various international economic diplomatic initiatives under the One Belt, One Road scheme.

Even without the outbreak of a real trade war with the US, a potentially more hostile America would be enough to worry Beijing, particularly at this juncture, as its economy is facing many domestic headwinds.

• The writer is a professorial fellow at the East Asian Institute, National University of Singapore.