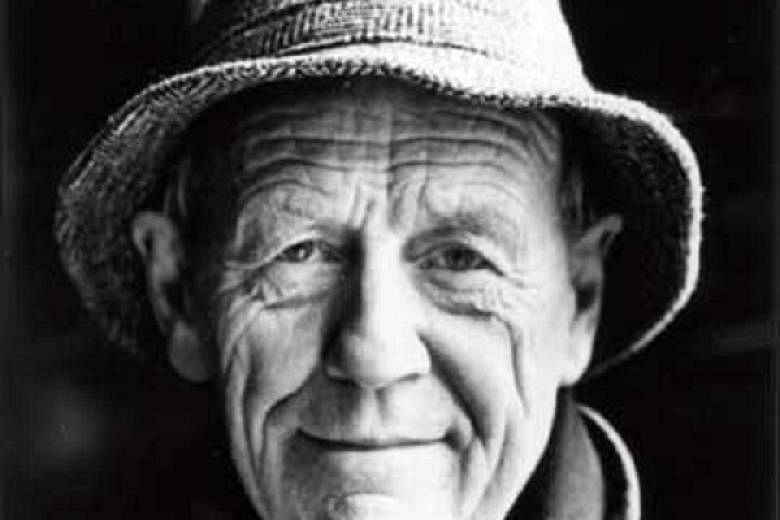

NEW YORK (NYTimes) - William Trevor, whose mournful, sometimes darkly funny short stories and novels about the small struggles of unremarkable people placed him in the company of masters like V.S. Pritchett, W. Somerset Maugham and Chekhov, died on Sunday. He was 88.

His publisher, Penguin Random House Ireland, confirmed that he had died but did not say where.

Trevor, who was Irish by birth and upbringing but a longtime resident of Britain, placed his fiction squarely in the middle of ordinary life. His plots often unfolded in Irish or English villages whose inhabitants, most of them hanging on to the bottom rung of the lower middle class, waged unequal battle with capricious fate.

In The Ballroom Of Romance, one of his most famous stories, a young woman caring for her disabled father looks for love in a dance hall but settles, week after week, for a few drunken kisses from a local bachelor.

The hero of The Day We Got Drunk On Cake repeatedly phones a young woman he admires in between drinking sessions at a series of pubs. The relationship deepens and, during a final call in the wee hours, takes a sudden, unexpected turn.

The emotional weather in Trevor's world is generally overcast, with a threat of rain. "I am a 58-year-old provincial," the narrator of the novel Nights At The Alexandra (1987) begins. "I have no children. I have never married." From this bleak premise, a mesmerising tale unfolds.

"I'm very interested in the sadness of fate, the things that just happen to people," Trevor told Publishers Weekly in 1983.

William Trevor Cox was born in Ireland in Mitchelstown, County Cork, to Protestant parents. His father, James, was a bank manager who took his wife, the former Gertie Davison, and children from one town to another, as promotions and transfers arose.

An outsider by family circumstance and religion in a predominantly Roman Catholic country, Trevor learned at an early age to observe quietly from the sidelines, a skill that served him well as an Irish writer describing the British, and as an expatriate looking across the Irish Sea to the towns and villages of his youth.

"I was fortunate that my accident of birth placed me on the edge of things," he wrote in The Guardian of London in 1992.

After graduating from Trinity College, Dublin, in 1950, he taught at a preparatory school in Northern Ireland. In 1952, he married Jane Ryan, whom he had met at Trinity. She survives him, as do their sons, Dominic and Patrick.

In secondary school, he had begun sculpting in wood, and his growing proficiency led to a job in England teaching art at schools in Rugby and Taunton as he developed a sideline carving statues for churches. He began showing in exhibitions and, working in wood, terra cotta and metal, he embraced abstraction.

In 1958, he published a wispy comedy of manners, A Standard Of Behavior (1958), which he later disowned. He also dropped his last name, to avoid confusion with his identity as a sculptor, although that chapter in his life was already drawing to a close. His abstract work, he later said, dissatisfied him because of its remoteness from humans. "I sometimes think all the people who were missing in my sculpture gushed out into the stories," he told The Times in 1990.

To bring in income, he began working as a copywriter at Notley's, a leading advertising agency in London, where he failed to produce a single useable line of copy, he once said. The job left him plenty of spare time, which he used to write fiction.

He grabbed the attention of critics in 1964 with The Old Boys, a blackly humorous account of former schoolmates who resume their old rivalries when they gather for a reunion. Evelyn Waugh called the novel "uncommonly well written, gruesome, funny and inspired," and it won the Hawthornden Prize. As a writer, Trevor was on his way, and Notley's lost one of the least promising copywriters it had ever hired.

For the next half-century, most spent in the Dorset countryside, Trevor turned out stories, novels and plays at a steady rate, developing an expanding world that readers came to recognise as Trevor territory, and a galaxy of characters that included the village sociopath of the novel The Children Of Dynmouth (1976), the fabulously boring Raymond Bamber in the short story Raymond Bamber And Mrs Fitch, and many variations on vacillating, timorous Prufrock Man.

"I don't think there is another writer from Ireland with his range," Gregory A. Schirmer, the author of William Trevor: A Study Of His Fiction (1990), said in an interview.

"With total conviction he has written about the rural Irish on their farms, about provincial towns, about commercial Dublin, about middle-class Protestants and the remnants of the aristocracy. He offers a complete picture of life on that island."