Staying alive after Nobel Prize

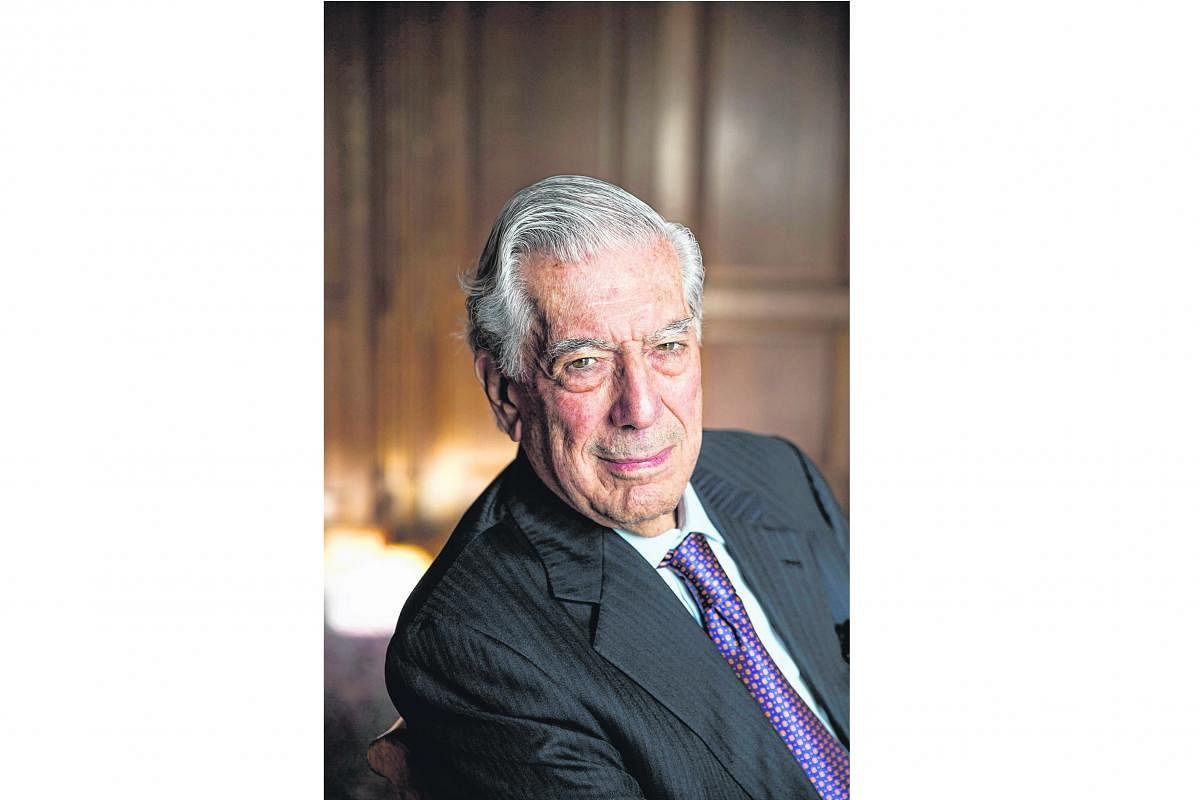

While proud to win the acclaimed prize in literature in 2010, Peruvian Mario Vargas Llosa says his struggle after that was to prove he had more to write

Winning the Nobel Prize in literature is a "great satisfaction", says Peruvian writer Mario Vargas Llosa, but its aftermath is mostly trying to prove you are not dead.

"There is a kind of prejudice against the recipients of the Nobel Prize in Literature," says the 81-year-old. "You are considered a finished writer. You have reached a point after which there is nothing. I received it in 2010 and, since then, I have been trying very much to prove that I am still alive."

Vargas Llosa is the last surviving great of the Latin American Boom, an explosion of writing from the region in the 1960s and 1970s that revolutionised world literature.

His late contemporaries included Julio Cortazar of Argentina, Carlos Fuentes of Mexico and fellow Nobel laureate Gabriel Garcia Marquez of Colombia.

"The Boom showed the world that Latin America is not only a continent of civil war, revolution and narcotics trafficking, but that it can also produce creative and experimental artistic and literary works," says Vargas Llosa over the telephone from his home in Madrid. He is a Spanish citizen, though he retains Peruvian nationality.

He rose to fame in his 20s with his debut novel, The Time Of The Hero (1963), about cadets at the Leoncio Prado Military Academy in Lima, which he had attended as a teenager.

His scathing portrait of corruption at the school led to the authorities burning 1,000 copies of the book in an official ceremony.

He is the author of 18 novels, from the 1977 semi-autobiographical comedy Aunt Julia And The Scriptwriter (like the eponymous scriptwriter, Vargas Llosa married his uncle's sister-in-law, Julia Urquidi, whom he later divorced) to the savage political epic The War Of The End Of The World (1981), about the cataclysmic Canudos insurrection in 1890s Brazil.

He has also written plays, essays and literary criticism.

His numerous accolades include the Miguel de Cervantes Prize, the highest award for a Spanishlanguage writer, and the aforementioned Nobel, which the Swedish Academy said was for his "cartography of structures of power and his trenchant images of the individual's resistance, revolt and defeat".

Since his win, he has not been idle. In the past seven years, he has produced essay collection Notes On The Death Of Culture (2015) and three novels, the most recent being Cinco Esquinas (2016), which is being brought out in an English translation as The Neighbourhood later this month.

In it, he revisits one of the most tumultuous periods of his life: the regime of Alberto Fujimori, the man against whom he ran for president of Peru in 1990 and lost.

Fujimori, an agricultural engineer of Japanese descent, came out of nowhere to beat Vargas Llosa by a landslide and went on to rule Peru for a decade, putting it through drastic economic reform.

But his efforts to defeat Shining Path, a Maoist insurgent group, involved human rights abuses such as the Barrios Altos massacre of 15 people, including an eight-year-old child, by members of a military death squad.

After a lengthy exile and extradition, Fujimori was sentenced in 2009 to 25 years in prison for graft and human rights violations. But he was pardoned in December last year by current president Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, which led to heated protests in the streets of Peru.

Fujimori's children, Keiko and Kenji, continue to be active in Peruvian politics, with Keiko having unsuccessfully run for the presidency twice.

Vargas Llosa was incensed by the pardon, which he thinks should be "considered treason by all democratic Peruvians".

"(Fujimori) was the worst robber we've had in our history," he declares. "Kuczynski has liberated a criminal who - for the first time in our history - had been democratically tried and condemned by civilian judges. Now everything is very confusing and nobody knows what's going to happen."

In The Neighbourhood, a seamy crime thriller, Vargas Llosa looks at how tabloid journalism was used to blackmail and discredit public figures during the Fujimori regime. The strings are pulled by a shadowy puppet master called the Doctor, who, in real life, was Fujimori's head of intelligence Vladimiro Montesinos.

Vargas Llosa, a former crime reporter, abhors what he calls "dirty journalism", the type that fuels gossip rags with juicy details of the lives of the rich and famous.

"It is very destructive of what should be the function of journalism in a democratic society, which is defending the truth... If you try to make public what should be preserved in the private sphere, I think it is not only politics which suffers, but also culture in general."

He himself has had trouble before staying out of the tabloids. He scandalised society in 2015 when he left Ms Patricia Llosa, his wife of 50 years and the mother of his three adult children, for Spanish-Filipino socialite Isabel Preysler, 66, a former beauty queen and the mother of pop star Enrique Iglesias.

Some 40 years before, he also made headlines for punching his close friend Garcia Marquez in the face at a movie premiere in 1976, leading to a 30-year feud.

Neither has ever divulged the reason for the spat, although many have speculated that it was over Vargas Llosa's wife Patricia.

Writing to solve the world's problems

Garcia Marquez, known for his novels One Hundred Years Of Solitude (1967) and Love In The Time Of Cholera (1985), died in 2014, leaving Vargas Llosa the last of their generation.

"It is sad to be the last one," he says. "But what is important is that their works are still there and they are widely read - not only in the Spanish-speaking world, but also through translations in different languages."

The Boom utterly changed the game for writers in the region, he says.

"I never thought, when I was young, that I could consecrate my whole life to writing. That was unthinkable for a young Latin-American. For the many young women and men writing today, it is difficult, but not impossible - and that is a great, great change."

But he is pessimistic about the kind of sway writers have on the public.

"I don't think writers have much power in our day. It was different in the past; writers were considered people with ideas that could be used in culture and politics. But this has changed completely in our times, in the civilisation of the spectacle."

This was precipitated by the digital revolution, he adds.

"Ideas have been, little by little, replaced by images. There is still a reading public interested in ideas, but this is a small minority now compared with the people who are using screens instead of books to be informed.

"But that doesn't mean that ideas are not important, and writers, journalists and people of culture should try very much to be committed to social and political problems, for the real solutions for these problems come from ideas."

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Straits Times on February 13, 2018, with the headline Staying alive after Nobel Prize. Subscribe