Singapore's architecture scene has been feted in recent times for its shiny skyscapers built by starchitects. A new book turns the spotlight back on the island's early historical gems.

Our Modern Past: A Visual Survey Of Singapore Architecture 1920s-1970s is written by Mr Ho Weng Hin, Mr Dinesh Naidu and Ms Tan Kar Lin - conservation advocates who say they penned this tome to help Singaporeans visualise the architectural value behind old buildings.

The concept for the book was partially influenced by Pastel Portraits (1984), a volume about Singapore's pre-World War II architecture, in particular the row house. It was authored by Gretchen Liu, a writer and early champion of the conservation cause here.

Mr Naidu, 40, a civil servant, says: "The book was a real impetus for the conservation movement. For example, it opened a lot of people's eyes to the conservation value of shophouses, which were considered slums in the 1980s before they were restored."

Our Modern Past features a wide range of building types: from schools to churches to even civil service quarters and flats, which might be seen as "ugly and grey", says Mr Naidu.

So he hopes the book will stir hearts and spur thinking about conservation, and deter demolition. He says: "In a way, we want to sensitise people and change their mindset and perspective."

He graduated from the National University of Singapore's architecture faculty with Mr Ho, 40, and Ms Tan, 38, who are married. The couple run architectural conservation specialist consultancy Studio Lapis.

Our Modern Past is largely a pictorial tome, published as three books. They cover various decades, starting from the colonial design period of the 1920s to the post- independence years, when public housing became one of the most pressing needs in independent Singapore. They end with 1978, with the Pandan Valley Condominium, an iconic suburban housing project near Holland Road which became known for its stepped-block look.

Collectively, the project features 649 photographs and each of the three books is written up in two sections: elements and feature buildings.

The elements section is like an architectural lesson for readers, exploring design elements such as form, type and materials that were popular in that period.

For example, tower-on-podium buildings such as the Malaysia-Singapore Airlines Building (1968) in Robinson Road gained traction in the late 1960s. Aside from having retail and public amenities, the podiums also provide shelter for pedestrians while the tower blocks are usually used for offices.

There are 34 design elements such as textured plaster, which was popularised in the inter-war years as an alternative to ornamental masonry; and fair-faced brickwork, which was used extensively after the war because it was cheaper than other options. Each element is illustrated with pictures of various buildings around town.

The next section features buildings that have used a combination of these elements. A total of 44 buildings are highlighted, including the old National Stadium and National Library, both of which have since been demolished.

It is a volume of epic proportions - and not simply in size. The project, which was funded by various sources including the Urban Redevelopment Authority Aude Grant, the National Heritage Board Heritage Project Grant, private donations from architects and in kind, took 10 years to complete.

Before this, the original idea for the book, which was taken on by another architect, intended to feature only 30 iconic buildings here. But that architect left the project and the trio "inherited" it. As the research gathered momentum, they collated a list of 400 buildings and decided to go in a different direction.

Ms Tan says: "We did extensive fieldwork and found that many buildings were still in existence - everyday buildings that people are familiar with. These would not have made it to the list of 30, so we decided to change the approach."

They divided up the research and worked on the project in their free time and from overseas, such as when Mr Ho went to Italy to pursue his master's degree for three years at the University of Genoa in 2005. They wrote thousands of letters to building owners to gain access for photo shoots. And they found material in the unlikeliest places.

On a trip to London for another work project, Mr Ho chanced upon old copies of Singaporean architectural journals, which had been sent there for record keeping. During the colonial years, Singapore's budding architecture fraternity was affiliated with the Royal Institute of British Architects, says Mr Ho, explaining the existence of these journals. Published inside were much-needed original building plans as well as photographs.

The team also conducted interviews with veteran architects such as Mr William Lim, whose work included the People's Park Complex in Chinatown; and Datuk Seri Lim Chong Keat, who worked on the Singapore Conference Hall in Shenton Way.

They even hunted down descendants of architects who had died such as Ms Sandy Lincoln, daughter of Mr Lincoln Page, a British senior architect with the Singapore Improvement Trust - the predecessor to the Housing and Development Board - who designed flats in Tiong Bahru, among other works. She shared a photograph collection of her father's work and was able to recall life in colonial Singapore.

Mr Ho says: "It was by luck we got to know that they were around and where to find them. We were hoping they might have kept their father's records or could tell us from their memories. There aren't many things written about them."

While the authors fulfilled their architectural passion project, launching the book was bittersweet as the photographer died before he saw it in print: Award-winning architectural photographer Jeremy San, who worked on the project alone, died from an illness two years ago, aged 36.

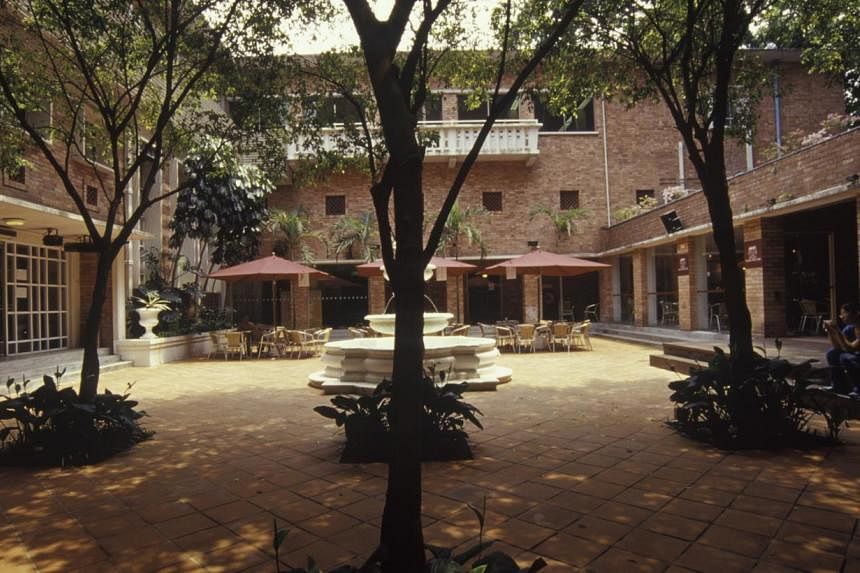

The authors fondly recall how Mr San, who was a runner-up at the 2012 Icon de Martell Cordon Bleu photography award, would go to each location multiple times, at various times of the day, to see how different the space would look.

For example, he captured a mesmerising image of the main staircase of the Market Street Carpark, which has been demolished. At about 4pm, the sunlight cast beautiful shadows through the latticed concrete walls onto the mosaic tiles, creating a stunning picture that played with shapes and light.

There is also a sense of nostalgia as the reader flips through the books, conjured up in part by his use of slide photography rather than a digital camera. Mr Ho says: "Jeremy was like a collector of these spaces and the way he photographed them is different. Looking at the pictures, you don't feel his presence in it, but rather, it is as if you are standing in the space yourself."

Even as this visual dictionary of Singapore's architectural history was launched last month, the authors are not taking a break, but are preparing for the debut of Volume Two next year - an encyclopaedia-like book on the modern architectural history of Singapore. It will also contain rare archival photographs and building plans.

But they have ruled out working on a similar book to their first volume, which would continue where they left off into the 1980s and onwards.

Given that they were born in the 1970s, Ms Tan says: "When you're contemporaneous to a building, you tend to go in with a more critical viewpoint because you know how it came to be. You'll question why it couldn't be better.

"But for these buildings, you'll see them with a historical perspective. We see it in its context - that it was a product of its time."

Our Modern Past ($120) is available at Books Kinokuniya Singapore Main Store; Times Bookstores outlets such as at Paragon, Cold Storage Jelita and Plaza Singapura; Tango Mango Books & Gifts; Select Books; and Basheer Graphic Books.

Iconic buildings in Singapore

1. National Library

Never has a building stirred up debate like the National Library.

The iconic red-brick building in Stamford Road was torn down in 2004 to make way for a tunnel.

The authorities also had to realign Stamford Road so that the Singapore Management University would have sizeable land to build on and traffic volume in the area could be managed.

Those in favour of keeping the building were outraged when the Preservation of Monuments Board said in 1999 that the library did not have "enough merit" to be gazetted as a national monument.

Alternative suggestions that would have preserved the building were rejected.

As students from the architecture faculty, Mr Ho Weng Hin and Ms Tan Kar Lin were vocal about their disappointment with the decision and that included writing letters to the press.

Anyone who has been to the library will probably cite the front porch as the most recognisable spot, as many once hung out there. Also iconic were the unpainted bricks, made in local kilns, which formed the facade. The library was officially declared open by former Singapore president Yusof Ishak on Nov 12, 1960.

There were plans to reconstruct the structure as a pavilion, but they were ditched because of technical and cost constraints.

2. Chee Guan Chiang House

Amid the shiny new malls and condominiums, this 77-year-old derelict structure is the house that Orchard Road forgot.

Completed in 1938, it was designed and built by Mr Ho Kwong Yew, one of the leading architects of the Modern Movement who also designed the original Haw Par Villa. Its style was a departure from traditional forms such as pitched roofs and ornate decorations.

The building in Grange Road, which is designed as a main house with a smaller house within it, was commissioned by Mr Chee Guan Chiang, the eldest son of the first chairman of OCBC group.

As the house of a rich man, it boasted an expansive garden, curved verandahs and spacious rooms. The occupants also enjoyed modern sanitation - a luxury at that time.

Looking at the interiors, it is likely that its owner threw extravagant parties. Enter the reception hall and a grand staircase flanked by stylish metal rails greets visitors.

The dramatic staircase is lit by natural sunlight streaming in through the rows of stained-glass panes, which were proof of the owner's opulent tastes.

The main house was given conservation status by the Urban Redevelopment Authority in 2008.

It is a popular haunt for photography buffs, despite it being closed off.

3. Post War Tiong Bahru "Red Flats"

Those who love to hear the birds sing will remember fondly these two blocks of public flats in Tiong Bahru Road.

Aside from housing two- and three-room apartments, there was also a coffee shop called Wah Heng on the ground floor of Block 53. Here, bird owners would hang their cages on a metal structure before catching up with friends over coffee.

Residents would refer to the twin blocks, completed in 1951, as "hong wu" or red house, as the original facade had a "burnt-brick red colour wash".

Each unit had a spacious verandah, while the roof terraces were a hive of communal activity as residents would head upstairs to catch the breeze, rest at pavilions there or dry their laundry.

It is the first public housing flats to be converted into a hotel. The Link Hotel was completed about eight years ago and has 150 rooms.

Our Modern Past's authors write that the renovations - these included closing verandahs and a pedestrian bridge linking the two flats - "appear to be unsympathetic to the original design intent of the Red Flats".

Jeremy San photographed the flats before renovation works started on the building.

4. People's Park Complex

With its loud green-yellow facade, the 42-year-old building in Eu Tong Sen Street is a landmark and the heart of Chinatown. The six-storey podium of shops and offices was completed and opened in October 1970 and the 25-storey residential block in 1973.

While mixed-use developments are common in Singapore today, the People's Park Complex was considered a pioneer in the genre when it was completed at the cost of $12 million.

The site was once an open public park before it was turned into Pearl's Market, with outdoor stalls. It was destroyed in a fire in 1966.

Design Partnership - now known as DP Architects, a successful home-grown firm - created the 102.7m-tall building in Brutalist style. The bulky, towering building was an in-your-face creation with its heavy usage of concrete. One celebrated zone is its "interlocking atria" where people gathered among kiosks on the ground floor, much like wandering among market stalls.

5. Change Alley Aerial Plaza

Shopping in a "mid-air shopping complex" (read: bridge with air-conditioning and stores) was a radical concept when the Change Alley Aerial Plaza was opened in 1973. It was designed by local architect KK Tan & Associates.

Featuring a rolled steel-glass paned bridge, which links Clifford Pier to Clifford Centre, the centrepiece of this plaza was the revolving Red Lantern restaurant at the top of the 12-storey tower.

There was also a lookout deck below the restaurant for members of the public to take in the view of the bay as they sipped drinks at the coffeehouse.

It was named after the Change Alley of London, where stockbrokers congregated, but it also housed money-changers who did business with visiting seamen and tourists.

Those who frequented Change Alley's shops - it was a mix of tailors, jewellers and those selling international souvenirs, among others - will remember its "futuristic space pods", which had curved shop windows. It also had a cafe along its tiled corridors.

The tower has since been conserved, while the bridge has been given a modern update.

However, the name Change Alley no longer exists. They are both now part of the OUE Bayfront, a commercial property which includes an 18-storey office tower at 50 Collyer Quay.

6. Victoria School

This storied school moved several times from Kampong Glam to Syed Alwi, which is near Victoria Bridge, before it settled at this Tyrwhitt Road location in 1933.

The school was designed by Public Works Department (PWD) architect Frank Dorrington Ward, who also designed the former Supreme Court.

During World War II, Victoria School was used by the Japanese and teachers had to follow a Japanese-only school syllabus. After the war ended in 1945, the school was used as a hospital for a short while before it welcomed students again.

The PWD experimented with school designs by building a multi-purpose hall above a naturally ventilated canteen in 1967.

After that, the all-boys school moved out in 1984 to its new home in Geylang Bahru. In 2003, it moved to Siglap Link.

Christ Church Secondary School used the Tyrwhitt Road site between 1985 and 2001. In 2007, the main classroom, administrative block, hall and canteen block were gazetted for conservation and turned into the People's Association (PA) headquarters in 2009.

Sources: Our Modern Past, National Library Board, URA