NEW YORK (NYTIMES) - In third grade, I wanted to be a mouse.

Not a timid mouse. Not a quiet mouse. And certainly not Mickey Mouse.

No, I wanted to be Ralph, the mouse with the motorcycle.

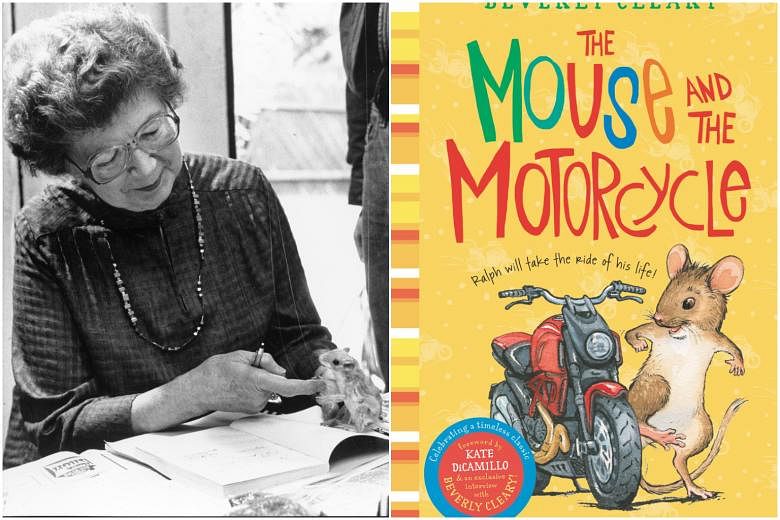

In the many appreciations of Beverly Cleary that have been posted since her death at age 104 on March 25, there has been plenty of rightful attention paid to Ramona, her most famous character. Though I have nothing but respect for Ramona, my heart has always belonged to Ralph. Cleary always said she wrote The Mouse And The Motorcycle for her son. In doing this, she didn't welcome just one boy into the world of her books; she welcomed generations of boys like me.

Third grade was a crucial time for me as a reader. I felt I was coming to a fork in the library aisles, where one path led to the Hardy Boys doing hardy boy things while Nancy Drew did mysteriously girl-coded things down the other.

Even though Marion Ravenwood was my favourite when we played "Raiders of the Lost Ark" (highly unusual, to the point of oddness), I still felt I needed to head for the mountainous boy-book terrain. I was supposed to read for action, not depth. Feelings were not a mystery the Hardy Boys ever needed to solve.

Then I found Ralph.

We meet him in Room 215 of the Mountain View Inn, where a boy named Keith has just arrived. (Keith's parents are in an adjoining room.) As soon as Keith settles in, he pokes around the room, coming very close to discovering the knothole behind which Ralph and his mouse family live. Then Keith does exactly what I would have done, had I been the one checking into Room 215: He takes out his toy cars, plays with them, and then lines them up in a neat row before he goes to sleep.

Like most boys my age (and some, but not nearly enough, girls), I had an abundant collection of Matchbox and Hot Wheels cars. Unlike most kids my age, I gave each of my cars a name and a personality, and it was usually the sedans that got the most play. While some of my cars raced, most of my time with them was spent on storytelling that I'd now call relationship oriented. In my hands, they came to life.

Because of this, I knew how Ralph felt, the first time he watched Keith play: Ralph was eager, excited, curious, and impatient all at once. The emotion was so strong it made him forget his empty stomach. It was caused by those little cars, especially that motorcycle and the pb-pb-b-b-b sound the boy made. That sound seemed to satisfy something within Ralph, as if he had been waiting all his life to hear it.

Cleary knew what she was doing. She was writing directly to the reader, showing that she knew us and what our lives and feelings were like. She helped me realise I didn't need to change myself into a detective or a knight or a Revolutionary War soldier in order to have an adventure or to be a boy. The adventure would come to me as part of the life I knew.

Claiming a book about a talking mouse as a work of realism might seem a stretch, but Cleary's magic was that she placed her flights of fancy so firmly in the lives of her very human characters that reading her stories always feels like soaring through real life. This was an inspiration to me as a reader and, later, as an author; it's not a coincidence that I can trace back my writing career to the stories I wrote in third grade.

Keith and Ralph bond over the fact that their parents tell them they get in trouble because they don't stop to use their heads. They talk to each other about how "you grow a little bit every day" but at the same time "it takes so long". The big quest in the book comes not when Ralph wants to show he's an alpha mouse, but when he needs to get an elusive aspirin for his new friend. The two of them care about each other in the way my Matchbox cars cared about each other, and that helped me understand such caring wasn't just acceptable, but necessary.

Like Judy Blume with her Fudge books, Cleary showed readers that books about boys didn't have to be junior versions of books about men; instead they could be tales of making it through the peculiar things life throws your way. Cleary - and Blume - also knew that once you gain devoted readers, you can take them into the better place where "boy book" and "girl book" categories have little meaning.

Ralph led me to Ramona. Fudge led me to Margaret and Deenie. All of them led to me and a number of my fellow kid-lit peers (male, female, non-binary) to becoming writers.

When Keith and Ralph first speak, Cleary writes, "Neither the mouse nor the boy was the least bit surprised that each could understand the other. Two creatures who shared a love for motorcycles naturally spoke the same language."

Cleary spoke the same language as so many kids, and so naturally. How wise of an author to use a mouse, a motorcycle and a boy who loves cars to guide me where I needed to go, as a reader, a writer and a human being.