SINGAPORE – When author Gwee Li Sui penned an op-ed for The New York Times in 2016 defending the “wacky, singsong creole” of Singlish, he was not only roundly rebutted by the Prime Minister’s press secretary, but he also received hate mail.

“There were really very fervent people saying, ‘Because of people like you, my children’s English will suffer’,” recalls the 53-year-old literary critic and poet, who admits to feeling “quite depressed” that the conversation quickly moved on from Singlish into mud-slinging from proponents and detractors.

The former assistant professor at the National University of Singapore’s Department of English Language and Literature and now full-time writer has since doubled down on his view that Singlish is a language. Gwee has gone on to write in and about Singlish in his best-selling Spiaking Singlish: A Companion To How Singaporeans Communicate (2017).

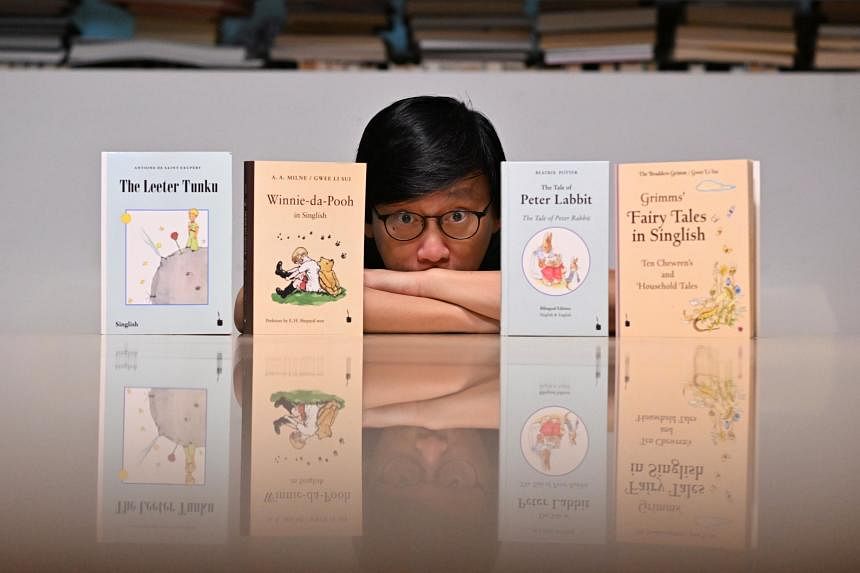

To bolster his case, he has been earnestly translating children’s classics into Singlish and has just published his fourth work.

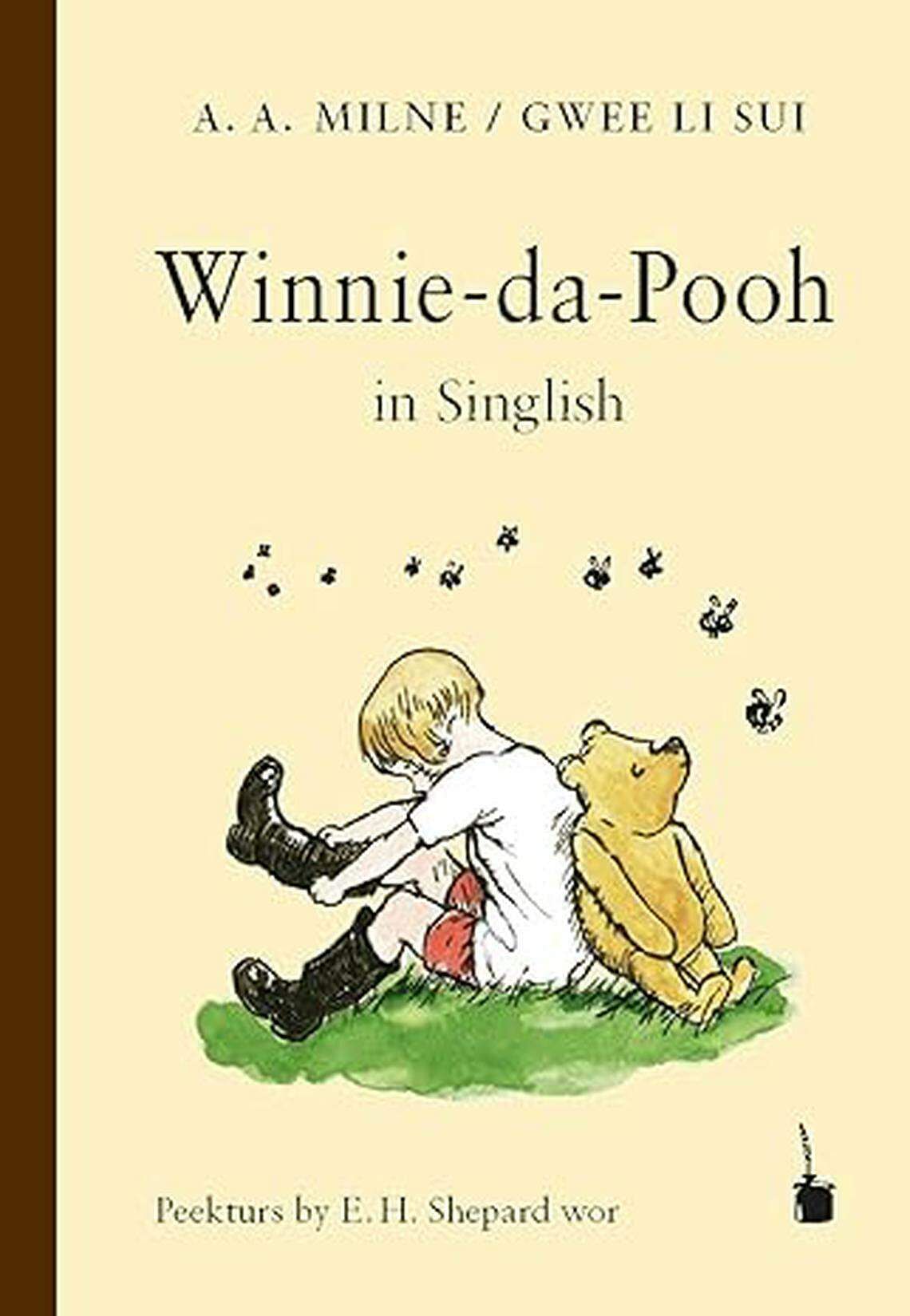

A line from Winnie-da-Pooh, his latest translation of A.A. Milne’s children’s classic Winnie-the-Pooh, reads: “Sometimes Winnie-da-Pooh suka play game when he downstairs.” (Suka is Malay for “like”.)

All his translations have been published by the linguist Walter Sauer’s Edition Tintenfass, a German press which has published children’s literature in more than 200 languages to date, including endangered and minority languages.

Although the books sell well, Gwee owns up to a feeling of “disappointment” when parents tell him they are buying these books for their children. He thinks his translations deserve to be read by adults too.

“Nobody has read a literary text in Singlish until now, so technically, everybody is an eight-year-old when it comes to reading Singlish,” says Gwee. “I’m also learning the art of translating.”

He found it challenging to coax the Singlish voice in his first book The Leeter Tunku (2019), a translation of Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s French classic The Little Prince. It was only when he started translating English writer Beatrix Potter and German folklorists Brothers Grimm that he grew more confident with his craft.

Still, Gwee is accustomed to negative comments from readers who insist that his Singlish is not accurate or that it contains too much “old people’s Singlish”. But that is exactly his point: the Singlish he uses in his translations belong not just to one person – certainly not himself.

“I’m quite conscious that every paragraph should have a mix of different languages,” he says, adding that he was also conscious to include young people’s Singlish, which may be influenced by global slang, the Internet and K-pop.

He says: “As long as it’s not one person hearing just his or her Singlish, I am in a good place. Hopefully, this will bring us together and we can hear one another’s Singlish and also our own.”

Gwee is aware that varying the vocabularies and registers of Singlish in Winnie-da-Pooh helps create a distinct personality for each character. For a book that thrives on word play, he had to find creative ways to translate the humour where there may be no Singlish equivalent.

To that end, he says his habit is to eavesdrop in public and “to have an ear in as many conversations as you can”.

He keeps a running document titled “Next book – Singlish words” on his laptop, tracking the ways Singlish is evolving as a living language.

But even as the use of Singlish is gaining wider acceptance in public campaigns and literature, Gwee is still mulling on a certain translation that he is not quite confident to bring out yet.

He has translated parts of the Bible – the world’s most translated text – and even consulted a theologian, but wonders if the public and his skills are ready.

“There is a lot of sensitivity involved. I need to get the translation to the point where we say that Singlish translations can bring out a range of emotions and not just humour.

“Right now, I think the most important thing is to get people comfortable with reading Singlish. Then, we can do more,” adds Gwee, who says he has been approached by readers to translate books by Jane Austen or the Mahabharata.

When he hears these suggestions, as he often does at his book launches, his reaction is that others can and should take on the work of translating books into Singlish.

“Look, I’m not the authority on Singlish. If anything, every Singaporean is an authority – or they believe they are the authority. That’s why they can comment on my translation.”

And if anyone does, he hopes they will get a better initial reception than he had. “I hope I am the last person to get hate mail for promoting Singlish.”

- Winnie-da-Pooh In Singlish ($27.73) by A.A. Milne, translated by Gwee Li Sui, is available from Amazon SG (amzn.to/47ezsBv). Catch a free reading of Winnie-da-Pooh by the translator during the Singapore Writers Festival at The Arts House on Saturday at 8pm.