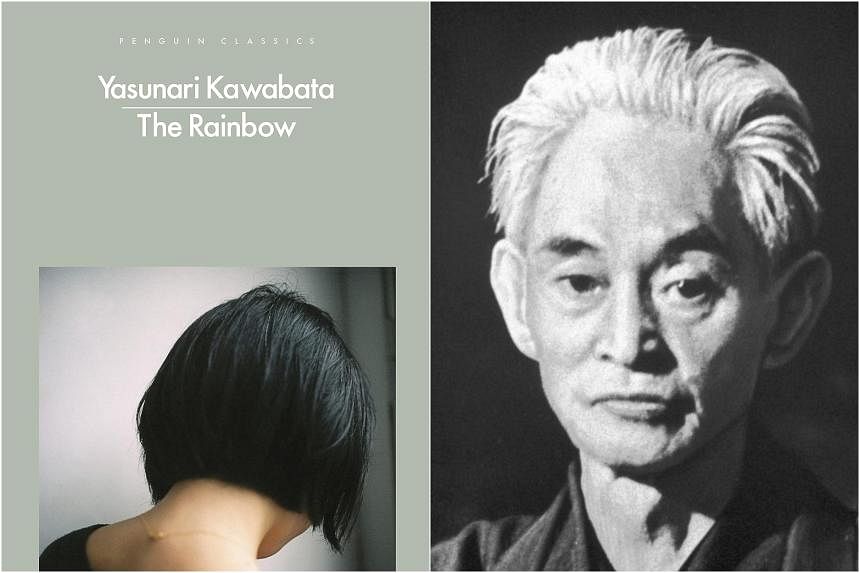

The Rainbow

By Yasunari Kawabata, translated by Haydn Trowell

Fiction/Penguin Classics/Paperback/224 pages/$30.44/Amazon SG (https://amzn.asia/d/cJ94ZQN)

4 stars

Yasunari Kawabata, who died at the age of 72 in 1972, was one of Japan’s most eminent writers.

He was the first of only two authors from the country to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, being recognised in 1968 “for his narrative mastery, which with great sensibility expresses the essence of the Japanese mind”. The other, Kenzaburo Oe, won in 1994.

The Rainbow, a minimalist work that was first serialised in Japanese between March 1950 and April 1951, is belatedly translated into English for the first time.

Japan, recovering from its defeat in World War II, was then under American Occupation. Kawabata, along with fellow literary luminary Yukio Mishima, feared the nation was losing the essence of what it meant to be Japanese.

Kawabata was clearly a tortured man, and his melancholic view of the world stands in stark contrast to the bright optimism conveyed by the titular Rainbow that appears over Lake Biwa, Japan’s largest lake, in winter.

One character opines that seeing a rainbow over the lake, with fields covered with rapeseed and milk vetch, “must be happiness itself”, though another describes it as “a tropical flower blooming in the snow or laying eyes on the lover of a deposed king”.

Kawabata’s sparse, delicate prose means little is explicitly said and plenty is implied – each gaze and gesture carries outsized meaning – and that in itself has its roots in a culture that traditionally leaves much unsaid with nuances that might be imperceptible to an outsider.

Also reflective of the norms of the era are gender roles: A single father who deftly changes the diapers of his baby daughter on the train is tsk-tsked and regarded “with something approaching pity”, while a teenager feels compelled to hide his homosexuality by romancing a woman.

They form a web of characters who meet and interact with Kawabata’s protagonists. Mizuhara Tsuneo is an eminent architect who doubts that “in much the same way as the advances of science had created new miseries for mankind... modern architecture would be able to increase people’s overall happiness”.

He has three daughters – each with a different mother – and the step-sisters are struggling to make sense of a rapidly changing world.

He lives in Tokyo with his two elder daughters. The eldest, Momoko, is haunted by the death of her kamikaze fighter pilot boyfriend Keita on a doomed mission to Okinawa in the war and seeks comfort with a series of flings, while Asako is frail and discovering love for the first time. The existence of their youngest step-sister Wakako, born to a geisha mother in Kyoto, is an open secret.

The narrative traverses the Tokaido Main Line – the nine-hour journey connecting Tokyo and Kyoto that is the predecessor of the shinkansen bullet train – interspersed with the colourful evocative vignettes of natural beauty, including of Kyoto in autumn and Hakone in winter.

Yet, there are plenty of psychological and emotional insecurities and spiritual wounds that will never heal: “You can try so hard not to push your loved ones into hell that you end up falling into it yourself.”

The characters in The Rainbow openly discuss a fast-changing Japan – “the houses of former nobles were being transformed into inns and restaurants” – and politics such as the devastating atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as well as of the Korean War (1950 to 1953).

Kawabata is suspected to have died by his own hand, though no suicide note was ever found, two years after Mishima died by seppuku (ritualistic suicide) following his failure to lead soldiers in an uprising against the top brass of the Self-Defence Forces, which he saw as being subservient to the United States.

Seventy years since The Rainbow was first published, it is a marvel to read, akin to a time capsule that reflects the Japanese psyche and social mores of a bygone, evanescent era.

If you like this, read: Snow Country by Yasunari Kawabata, translated by Edward G. Seidensticker (Vintage, 1996, $20.77, Amazon SG, https://amzn.asia/d/4Xngnet). A wealthy dilettante meets a geisha in an affecting tale of forbidden love, set against the desolate beauty of a wintry isolated mountain hot spring town. First published in Japanese from 1935 to 1937, the novel is regarded as one of Kawabata’s best works.