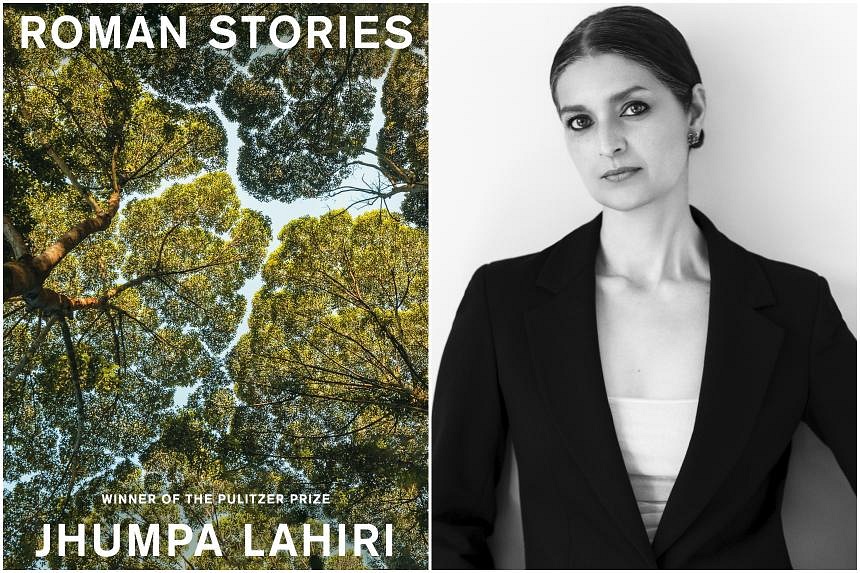

Roman Stories

By Jhumpa Lahiri, translated by the author and Todd Portnowitz

Fiction/Alfred A. Knopf/Paperback/204 pages/$36.63/Amazon SG (amzn.to/47y7rEh)

3 stars

Rome is one of those cities that nigh everybody has an idea of. Whether it is the endless adventure in Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960) or the dangerous mystique in Dan Brown thrillers, its representation in popular media has given it its own mythology.

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jhumpa Lahiri’s title for her short story collection is taken from another classical representation, Alberto Moravia’s Racconti Romani, or Roman Tales, published in 1954.

Except she subverts all ideas of Rome and writes from the perspectives of immigrants, the overlooked other growing in population in the Eternal City and whose place is simultaneously more fundamental to the city’s functioning, but also more precarious.

The author, born in London to Indian immigrants, wrote these stories originally in Italian, the language of her adoptive city where she lives half the year. Three of the nine short stories are translated by Todd Portnowitz; Lahiri worked on the rest herself.

It is a breezy read, Lahiri precise in her sentences, sometimes even bordering on the minimalist. In The Boundary, the daughter of a villa’s caretaker fusses over a family who has rented the villa to stay, observing them as they easily take over the house as if it is their birthright.

Her feelings are inexplicit, contrasting only the visitors’ garrulity with the quietude of her father, whose speech is garbled after he was beaten up by thugs in the city. Work for her continues after they leave as she surveys the items they have left behind.

Later, in Well-Lit House, an immigrant family is chased out of their apartment by the collective action of hostile neighbours, despite their hopes that “a well-lit house can change your life”.

In The Delivery, a woman is shot on a whim by two boys on a motorino while out on an errand.

“Go wash those dirty legs,” she is told, the last thing she hears before her head hits the tarmac.

In all these stories, the characters are unnamed and Lahiri never reveals their ethnicity, alluding only to their foreign-ness with phrases like someone’s wife being from “my country” or the wearing of the hijab.

Rome, despite its beauty, is shown to be in decay, with xenophobic slurs scrawled on the walls. The rich find every opportunity to decamp to their summer and winter homes elsewhere, leaving their homes in the temporary care of their immigrant employees.

What Lahiri does best is showing the complicated feelings of ownership and regret felt by the immigrants. An older immigrant watches her younger counterpart fitting in and she “nearly dies from envy”.

The problem is that many of the stories are too short or simplistic to mean much more than a straightforward recovery of marginalised voices – a project no doubt with its own value but is, on its own, insufficient for Lahiri’s stratospheric standards.

Two stories in the first third, P’s Parties and The Re-entry, though, have some potency. The former gives readers a different idea of the foreign in the form of an Italian man’s wishful affair with an expat. Rome’s cosmopolitanism becomes also a site of intrigue.

The Re-entry sketches a subtle portrait of degrees of belonging as two friends, one more local than the other, meet in a restaurant.

“In the end, she has no personal link to the history she studied,” the character who considers herself naturalised realises. “Nor will she ever experience the comfort of having lunch in a trusted restaurant that forms part of her family’s history.”

If you like this, read: Death In Rome, by Wolfgang Koeppen, translated by Michael Hofman (Hamish Hamilton, 1992, $28.30, Amazon SG, amzn.to/3O4rAuJ). Yet another novel set in Rome, following the four members of a German family in the decaying city after World War II. Its publication in 1954 provoked great controversy in Germany for its portrayal of a former Nazi officer.