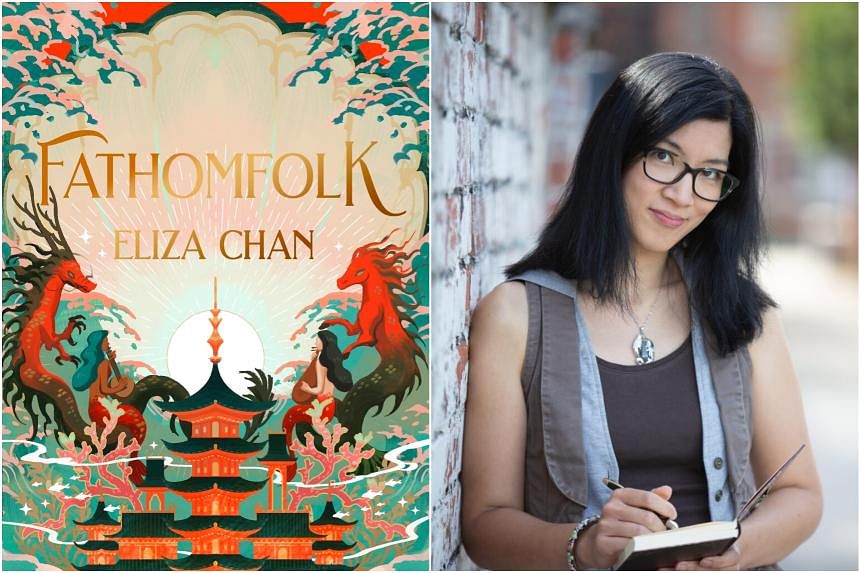

Fathomfolk

By Eliza Chan

Fantasy/Orbit/Paperback/448 pages/$22.37/Amazon SG (amzn.to/3SEQSCp)

Three stars

Swim aside, Aquaman – the most immersive watery fantasy of late is no superhero blockbuster, but a debut novel inspired by East and South-east Asian mythology.

Scotland-born, Manchester-based author Eliza Chan has plumbed the lores of multiple cultures to create the world of Fathomfolk.

In the semi-submerged city of Tiankawi, humans live in uneasy co-existence with “fathomfolk” who have migrated from the increasingly polluted deeps.

While some have made it to the higher echelons of Tiankawi, most fathomfolk emigres eke out hardscrabble livelihoods in the city’s depths, restrained from even violent thoughts against humans by the pakalots, or manacles, that they are forced to wear.

Mira – half-human, half-siren – was raised in poverty by an immigrant single mother, but has risen to become Tiankawi’s first fathomfolk captain of the guard.

But despite her new rank and her relationship with Kai, a water dragon prince, she struggles to reconcile the two worlds she straddles, one of which she must now police against her better judgment.

Further complicating matters is the arrival of Nami, Kai’s rebellious little sister. Exiled to Tiankawi for misbehaviour, she falls in with the fathomfolk extremists who call themselves the Drawback. The group is fomenting revolution – at a bloody cost.

Chan fills her pages with a plethora of watery creatures, from better-known species, such as the kelpie of Irish and Scottish folklore and the Japanese kappa, to the more obscure, such as the Korean jangjamari or ikan keli (Malay for catfish).

They populate a world vividly assembled from a “rojak” of Asian cultures. The dish itself gets a mention, as do other familiar foods such as pandan and mango sago pudding.

Chan admirably chooses not to explain most of this in either footnotes or glossary, trusting the reader to work it out from contextual clues or use Google.

The busy narrative is helmed for the most part by characters more righteous than riveting, whose romances feel like plot contrivances.

It is at its most buoyant when dealing with Cordelia, a shapeshifting sea-witch with a tentacle in every shady aspect of Tiankawi’s underworld. Her moral murkiness makes her the most compelling character by far.

Chan has succeeded in creating a richly detailed world that also functions as a parable for the climate refugee crisis. Despite the magical setting, the novel contains scenes of xenophobia, police brutality and trafficking that feel plucked from real-life news stories.

With global warming causing sea levels the world over to rise, Chan’s fantasy floats an urgent warning to the surface.

If you like this, read: The Scar by China Mieville (Macmillan, 2002, $22.56, Amazon SG, go to amzn.to/3ucIAZh). Translator Bellis Coldwine is on the run from her dystopian home city when her ship is hijacked by pirates and she is press-ganged into joining Armada, a massive floating city made up of thousands of ships that serves as a haven for refugees, rebels and criminals.