NEW DELHI - Earlier this month, Mr Mohammed Ajaz queued at a government Covid-19 vaccination centre in Noida, on the outskirts of the Indian capital New Delhi, to see if he could secure his first dose. But there was a huge crowd and the 41-year-old fruit and vegetable vendor returned home, dejected.

The daily wage earner could not afford to wait. "I had already got my vegetables for the day and did not want them to rot," he said.

Mr Ajaz faced another obstacle - he did not have a slot booked on Co-WIN, a government portal. Indian citizens between the ages of 18 and 44 must register on the portal and then book their appointments for vaccination on it.

He has heard of Co-WIN and owns a smartphone, but the illiterate vendor had no idea how to book an appointment on the portal. "Other than talking, I use my phone only to check how much money has been sent by my customers," added Mr Ajaz, who could not recollect his phone number.

While vaccine shortage has severely curtailed India's vaccination campaign, the digital divide has compounded this problem by excluding have-nots and those uninitiated, such as Mr Ajaz.

There are around 103.98 Internet subscribers per 100 people in India's urban areas and just 34.6 in rural parts.

This inequity is compounded as digitally suave urban folk secure vaccination spots, often using online services that alert them to vacant slots, in rural areas near where they live.

Just around 3 per cent of India has been fully vaccinated and the drive has fallen behind in rural areas with reports indicating only around 12 per cent of its residents had received their first dose, while 30 per cent of those living in urban areas had done so.

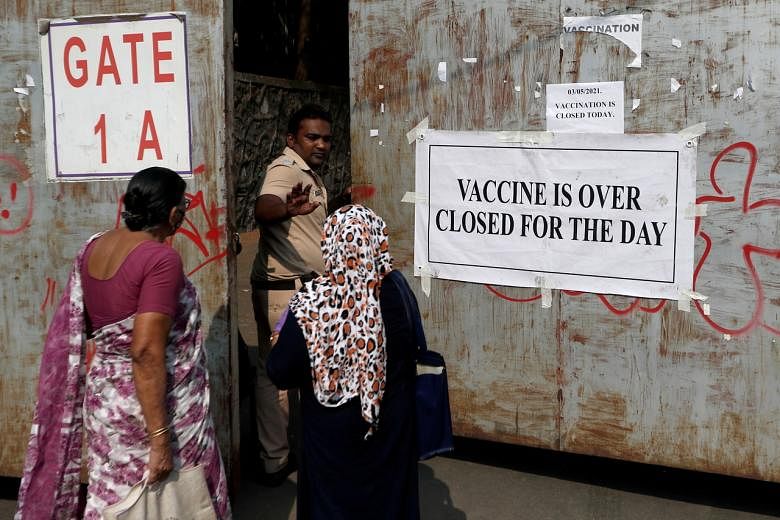

Only those 45 and above are currently allowed to get a jab without a prior appointment, but such walk-in drives have become increasingly rare with the ongoing vaccine supply crunch.

Several efforts are under way to try and bridge this divide. Spice Money, a rural fintech company, launched an initiative last week that has roped in 600,000 of its representatives spread across the country to widen the vaccination net.

While their outlets have served as last-mile banks since 2016, allowing people to withdraw money where such infrastructure is non-existent, these representatives now double as vaccination agents.

They encourage people to get vaccinated, register them on Co-WIN through Spice Money's app and portal and even help them secure vaccination slots. Mr Dilip Modi, the founder of Spice Money, told The Straits Times, there is a need for such intermediaries in rural India.

"There is a (digital) divide and while smartphones and the Internet have reached villages, I think the whole comfort of being able to transact digitally and be able to engage digitally is not so pervasive," he added.

Even within cities, the urban poor and homeless form a vulnerable population who are being cast aside in the vaccination drive. More than 1.8 million people in India are homeless, and many of them do not have a phone or access to the Internet.

In New Delhi, the Centre for Holistic Development (CHD), has been working to convince such people to get vaccinated. The organisation has so far managed to get around 1,500 homeless and other vulnerable individuals registered.

"This number should have been more but many do not have the documents necessary for registration," said Mr Sunil Kumar Aledia, CHD's executive director. Around 800 of those registered have received their first dose of the vaccine.

Government officials have said mandating prior appointments helps prevent crowding at vaccination centres. Those who cannot access the online portal can register themselves at government-run Common Service Centres, which deliver online services.

But The Indian Express reported only 54,460 of the 300,000-odd such centres were operational as at May 11, accounting for approximately 170,000 registrations on Co-WIN or just around 0.1 per cent of total vaccine doses administered.

This week, the government announced that the Co-WIN portal would be made available in Hindi and 14 other languages in the country to make it more accessible.

In Mumbai, an initiative by the Tata Institute of Social Sciences has managed to register 1,171 individuals and have 874 of them vaccinated with their first dose.

The Community Led Action, Learning and Partnership's (Clap) vaccination initiative that began last month relies on around 55 "community resilience" fellows who target lower-income neighbourhoods in the city's M East ward.

"The government doesn't have a very aggressive positive vaccination communication strategy and because of that, misinformation has spread faster than real information," said Dr Avinash Madhale, Clap's senior programme coordinator, highlighting how vaccine hesitancy still remains a challenge.

He added that setting up more walk-in vaccination camps should be an "absolute priority" for the government. "I definitely believe more efforts have to be made to get away from this kind of technological limitation and make vaccination simple and accessible," he told ST.

Mr Ajaz now hopes for one such walk-in drive in his village. "Some will benefit from this online model but it is not convenient for those like us," he said.