BUSAN, SOUTH KOREA (AFP) - A new documentary sheds light on the little-known story of North Korean war orphans sent to Poland, where they formed an unlikely bond with their teachers before their traumatic return home.

The Children Gone To Poland - which premiered on Saturday (Oct 6) at the Busan International Film Festival in South Korea - traces the journey of the 1,200 orphans sent from the North during the 1950-53 Korean War.

The devastating conflict, which sealed the division of the flashpoint peninsula, killed at least half a million civilians and left at least 100,000 children without parents.

The North's then leader Kim Il Sung sent thousands of orphans to countries including the Soviet Union, Hungary and Poland from 1951, pleading with his communist allies to take care of them.

The group of 1,200 orphans arrived in 1953 at the small, forested village of Plakowice, where they lived in a former hospital building for six years under the care of Polish teachers.

Famed South Korean actress Choo Sang-mee, who directed the film, visits Poland to find traces of the war orphans, alongside a North Korean defector with her own distressing childhood memories of separation from her family.

"Trains full of children arrived (over) several days," retired teacher Jozef Borowiec said in the film, adding many were in a "state of shock and trauma" after witnessing the horrors of war.

'HEARTBREAKING MEMORIES'

The orphans, infested with lice and suffering from disease, insisted on sleeping under the bed in fear of the bombing campaigns they lived through at home, while constantly screaming and crying in their sleep.

But they quickly learned Polish and formed bonds with their teachers and caregivers, who knew from personal experience the horrors of war.

"Back then, we also went through horrible wars and had many heartbreaking memories ourselves," Borowiec, 91, told Choo.

"We told them to call us mum and dad... We wanted to do everything to help these (North Korean) orphans erase the memories of war and have a sense of family in Poland," he said, wiping away tears.

Old photos and videos showed the orphans laughing, studying Polish, dancing and singing, or playing with teachers and other Polish children - a typical childhood denied in their homeland.

The teachers soon got to know each of them - whose names they tearfully remember even decades later.

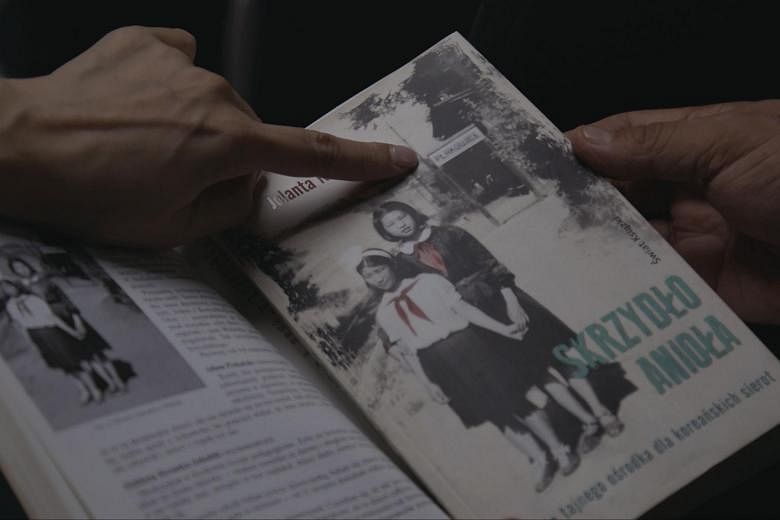

"The children were brought here as part of international propaganda (to cement diplomatic ties)," Jolanta Krysowata, a Polish journalist who wrote a book about the North Korean orphans, says in the film.

"But the teachers developed real compassion for these orphans... the human feelings they shared with the children had little to do with politics," said Krysowata, whose book inspired the latest documentary.

FORCED RETURN

North Korea eventually ordered the children to return and join the country's post-war reconstruction efforts, prompting some to lie on the snow and even pour cold water over themselves in a desperate bid to fall sick and avoid repatriation.

Many sent letters back to the teachers, describing their days in Poland as the best time of their lives and bemoaning the backbreaking labour they faced back home.

One child died during a failed attempt to illegally cross the border to neighbouring China, after sending multiple letters begging Borowiec to take him back.

All letters came to a sudden stop in 1961 as the North's regime limited contact with the outside world.

The film juxtaposes the fate of the orphans with those of today's North Korean child defectors, traumatised by the harrowing escape from their homeland.

The impoverished, isolated state is still under the tight grip of the Kim dynasty that has ruled through three generations with an iron fist and has little tolerance for dissident.

The film shows young North Korean refugees in Seoul telling their childhood memories of losing parents to famine, or witnessing the gruesome death of a sibling in a gulag.

"There are always children who suffer in times of historic turmoil, but they are forgotten as the history eventually heals itself and moves on," said director Choo.

"History erases the story of these children in its path to the future. But some children transform their pain to the strength to live, and they grow."