Professor Bertil Andersson looks at the cans of soft drinks on the coffee table, comically thumbs his nose and pronounces dramatically: "Please get me a real Coke, not these bloody Coke Lights."

He is holding court in the lounge room of the President's Lodge, which sits on a hill in the sprawling Nanyang Technological University (NTU) campus. Used to host visitors, it has a verdant garden which offers a commanding view of the Jurong West heartland.

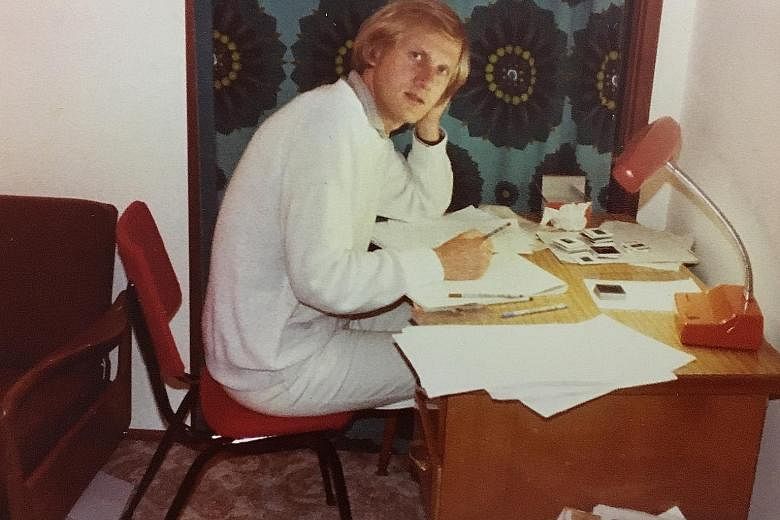

"If someone had told me in the 1950s that I'd one day be sitting here, a blue-blooded professor, the president of a top university in Asia, I would have said it was totally improbable and inconceivable," says the 68-year-old.

"It is totally unreal," adds Prof Andersson, who last week received the 2016 President's Science and Technology Medal for steering NTU beyond engineering into new fields, including environmental science and medicine, and transforming it into a world-class university.

If serendipity had not stepped in, he says, he would probably have ended up a factory worker or continued working on the farm that his family has owned since 1830 in Sjobacka in Sweden.

"I was a simple guy from the Swedish forest," says the elder of two children of a metal factory worker and a housewife.

His deeply religious working-class parents harboured no ambitions for their children.

He recalls: "They thought reading was a waste of time. They'd say, 'Why are you sitting there reading when you could be helping your grandpa harvest apples?'"

His saviour was his maternal grandmother, who "changed my destiny".

"She was a tough lady. She ran the farm and she was powerful. Even though she was not educated, she had a very creative mind," he says.

Waving away his parents' protests, the matriarch decided her favourite grandson should study.

"That's how I went to senior high school and later, university.

"My cousins and my sister never got to do that. I was the black sheep of the family," he adds, letting out a big bellow.

Bucking his parents' expectations meant there was no room for failure.

"It meant I could not go back to my father after three years in university and tell him that I failed. That would have been a total disaster," he recalls.

So he worked hard, something not alien to him.

From the time he was nine until he was 17, he worked part-time as a newspaper delivery boy.

"I did it because I had less money than my peers. When they had hamburgers, I could afford only a hot dog," he says.

After completing high school, he left for Umea University, a cutting-edge institution 1,000km away in the north of Sweden.

"I wanted to be far away because I wanted the space," says Prof Andersson, who majored in biochemistry and minored in journalism.

The first year, he says, he almost studied himself sick.

"Chemistry and biology were demanding, you had to read a lot and there was a lot of lab practice.

"And in the north, you have winter seven months of the year, and for three months, you hardly see the sun," he says, shaking his head.

An outstanding student, he went on to do his master's in Umea in 1974, and then completed his PhD and Doctor of Science at Lund University in 1978 and 1982 respectively.

Becoming a plant scientist was not part of his game plan.

He had set his sights on researching the brain and its rapid reactions for his master's.

"My professor said, 'We don't have the resources for that here. Why don't you study plants? Their biochemical reactions are just as interesting,'" he says.

That became another game changer. Prof Andersson became a pioneering plant biochemist, blazing trails in artificial leaf research where sunlight is tapped to produce sustainable energy.

"When we burn fossil fuels today, what we are doing is to reverse more than two billion years of photosynthesis. I'm like an industrial spy sent to find out what kind of mechanics plants have evolved to provide the green solar panels of nature," says the scientist, who has authored more than 300 papers on the subject.

"If we can devise artificial photosynthesis, if we could figure out its blueprint, we might have the ultimate solution to our energy crisis."

His research bagged him a fellowship from the European Molecular Biology Organisation and in 1979 a research stint at the Australian National University in Canberra.

The trip Down Under involved a stopover at the then Paya Lebar Airport in Singapore.

"It was perhaps a sign from the sky that I would end up here," he says jocularly.

By then married to his first wife, an accountant, he lived in Australia for two years.

"Mathilda, my elder daughter, was born there. Two years later, she came to Singapore before she went back to Sweden for the first time. That was another sign from the sky," says the scientist who has two daughters, aged 34 and 36. He and his first wife divorced after 25 years of marriage.

At 36, he was made full professor at Stockholm University.

His career kicked into high gear. Not only did he become a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, but also he became one of the youngest members to sit on the Nobel Prize selection committee for chemistry.

"I was only 38 then, and still had a lot of hair," he says, adding that he became the committee chairman several years later.

Being in the Nobel Foundation changed his life too.

"It opened a lot of doors. I'd probably not be recruited here if I didn't have that on my CV," he says.

It was also the first time that his father finally realised that his son was someone important.

In 1989, as a member of the Nobel committee, Prof Andersson stood next to the King of Sweden and gave a speech on national television.

"For the first time, my father said something. He said if you were standing next to the King on national television, you must be somebody."

So what does he think of Bob Dylan getting this year's Nobel prize in literature? "I think it should have been (John) Lennon," quips the music fan, who has performed Beatles numbers in NTU on a couple of occasions.

Hungry for new challenges, he left his cushy job at Stockholm University to become president of Linkoping University in 1999.

Four years later, Stockholm University beckoned with the same position.

"At the same time, I got a phone call from the European Science Foundation (ESF) asking me to be the head to promote European research," says the professor, adding that the position attracted 650 applicants.

Finding himself in a dilemma, he consulted the then Swedish education minister on what he should do.

"The minister thought about it for three minutes and then told me, 'Europe needs you more.'"

The work, he says, was challenging. "You're working with people from 30 countries. The difference between a Greek and a Finn... It was complicated," he says.

In 2005, Singapore's National Research Foundation invited him to be a member of its science advisory board to advise the country on science and technology strategies.

Two years later, NTU asked if he would become its first provost.

Impressed by the country's determination and financial resources to become an international research centre, he accepted the position.

"I was 59 years old and at that stage in my career, I told myself I could afford to take some risks," he says.

Many told him that he was foolish to give up his prestigious job at the ESF and that coming to NTU was a step down.

"I said, 'Maybe in Europe, we talk too much. In Singapore, they act.'"

By then, he had met his second wife, Dr Susana Geifman Shochat, now associate professor at NTU's School of Biological Sciences.

"I met her in Jerusalem when I was on a sabbatical. She was also doing plant research. You guys don't understand. The lab is a very romantic place," he says with a chortle.

"NTU was a little in the shade when I came but I saw the potential. It was an undelivered baby," he says.

As provost, his work, he says, was cut out for him: He was the change agent. "My job was to get research on the main agenda. We should not just teach, we should be doing research. We should be getting fresh food, not just tinned food," he says.

Achieving that objective meant setting up a new tenure system.

About 20 per cent of teaching staff were let go over a period of two years because they did not meet the standards of the university's new ambitions.

"We were not complacent, it's obvious in the rankings," says Prof Andersson who was made NTU president in 2011, after more than three years as provost.

Indeed, according to the Quacquarelli Symonds World University Rankings - one of the most established and recognised in the world - NTU vaulted from 74th position in 2010 to 13th this year.

Last year, Times Higher Education ranked it the world's fastest-rising young university.

"Many professors are proud of the change. It doesn't mean that everything is perfect. Universities are very complex entities involving politicians, industrialists, parents and students. I have to please everyone at the same time," he says.

Asked about the media storm surrounding well-known media professor Cherian George not given tenure last year, he says that he has nothing to add to what has already been reported.

Prof Andersson, who sits on the boards of several international foundations and Singapore organisations including the Agency for Science, Technology and Research, says the new item on his agenda is breaking down silos.

Interdisciplinary thinking and complexity research, he says, is vital in an increasingly complex world.

"The climate is a complex system, Singapore is a complex system, economies are complex systems with hundreds of parameters interacting.

"We cannot afford to look only at the molecular details. It's very important to break down walls."